President Donald Trump shakes hands with Gen. Mark Milley, then-chief of staff of the Army, during the 58th presidential inauguration parade in Washington, DC, on Jan. 20, 2016. US Army Reserve photo by Master Sgt. Michel Sauret.

Last week, former President Donald Trump led calls that Mark Milley, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, should face a charge of “treason” based on explosive allegations of backroom maneuverings in a new book by two veteran journalists.

But in the scope of American history, the legal charge of treason — which carries the death penalty — has only been leveled a handful of times. Among those charged: an al Qaeda recruiter, a man who tortured American prisoners of war during World War II, and a conspirator in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln.

As Milley’s defenders and legal scholars pointed out, treason is an exceptionally rare charge because it requires exceptionally grievous acts and an exceptionally high burden of proof — though that has not always been the case.

So what, exactly, is “treason”?

As the only crime specifically enumerated in the US Constitution, treason was considered dire enough by the country’s founders for them to devote an entire clause in Article III to its definition. And yet treason cases have been vanishingly rare in modern America.

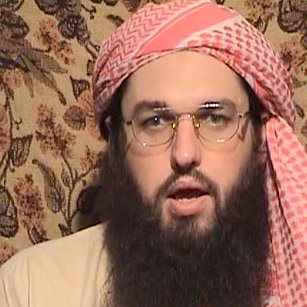

The most recent case — which never reached a courtroom — was in 2006, against an American man who had joined al Qaeda and made propaganda videos that were widely used as recruiting tools by the terrorist organization. Adam Yahiye Gadahn, born Adam Pearlman in Oregon, was indicted in the Southern Division of the United States District Court for the Central District of California. However, the US never actually captured Gadahn, who was known as “Azzam the American.” He was killed in a 2015 drone strike in Pakistan.

The last American convicted of treason was Tomoya Kawakita. Born in the US to Japanese parents, he graduated high school in California but then went to Japan for college. When World War II broke out, he worked as a translator at a POW camp in Japan where, prisoners later testified, he took gruesome pleasure in torturing Americans. After the war, Kawakita — invoking his US citizenship — returned to the US and was recognized by a former POW at a Los Angeles department store.

A jury deadlocked for days but finally convicted him of eight charges of treason and sentenced him to death.

Citing the language of the Constitution and claiming to have renounced his US citizenship while in Japan, Kawakita argued that he could not be convicted of treason because he was not a US citizen when he committed his crimes. The Supreme Court disagreed, though Kawakita was never executed. President Dwight D. Eisenhower commuted his sentence to life imprisonment and a $10,000 fine, and President John F. Kennedy had Kawakita deported to Japan, barred from ever returning to the US.

Why are treason cases brought so infrequently? One reason is the very limited number of details provided in the law itself. According to the Constitution (which refers to the United States in the plural as “them”):

“Treason against the United States, shall consist only in levying War against them, or in adhering to their Enemies, giving them Aid and Comfort. No Person shall be convicted of Treason unless on the Testimony of two Witnesses to the same overt Act, or on Confession in open Court. The Congress shall have Power to declare the Punishment of Treason, but no Attainder of Treason shall work Corruption of Blood, or Forfeiture except during the Life of the Person attainted.”

Many states have their own nearly identical treason laws on the books.

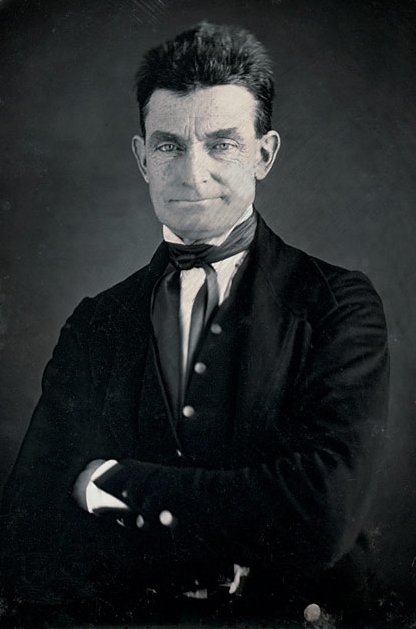

The term that makes treason unique is “levying war,” which raises the charge beyond an act of violence or damage and requires that treason can only apply to those who are committing an act of war. In early American case law, acts of overt rebellion like the Whiskey Rebellion, Fries’ Rebellion, and the Dorr Rebellion all led to treason prosecutions on grounds of “levying war.” Abolitionist John Brown’s failed slave uprising at Harpers Ferry in 1859 resulted in a conviction by the commonwealth of Virginia and the first execution for treason in the country’s history, albeit on the state level.

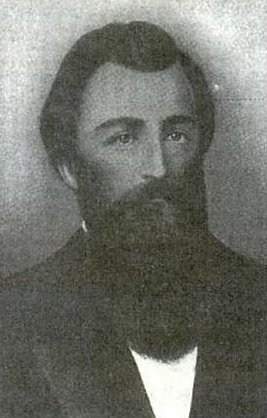

The first and only federal execution for treason came in 1862, during the Civil War, when William Bruce Mumford tore down an American flag that Marines had hung at the local mint in New Orleans. He was convicted by a military tribunal in a single day and hanged in a public square.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, his death — delivered without serious due process for tearing down a flag — became a rallying cry for Southern secessionists.

Last week, Milley sparked another cry of outrage with reports that he had, according to two Washington Post reporters, spoken with his Chinese counterpart during moments of high tension around last year’s election and just after the Capitol riots of Jan. 6, and he insisted that his underlings keep him informed should President Trump order the use of nuclear weapons.

Read Next: Should Gen. Milley Be in Jail? The Facts Behind the Milley ‘Treason’ Scandal

Maggie BenZvi is a contributing editor for Coffee or Die. She holds a bachelor’s degree in political science from the University of Chicago and a master’s degree in human rights from Columbia University, and has worked for the ACLU as well as the International Rescue Committee. She has also completed a summer journalism program at Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism. In addition to her work at Coffee or Die, she’s a stay-at-home mom and, notably, does not drink coffee. Got a tip? Get in touch!

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.