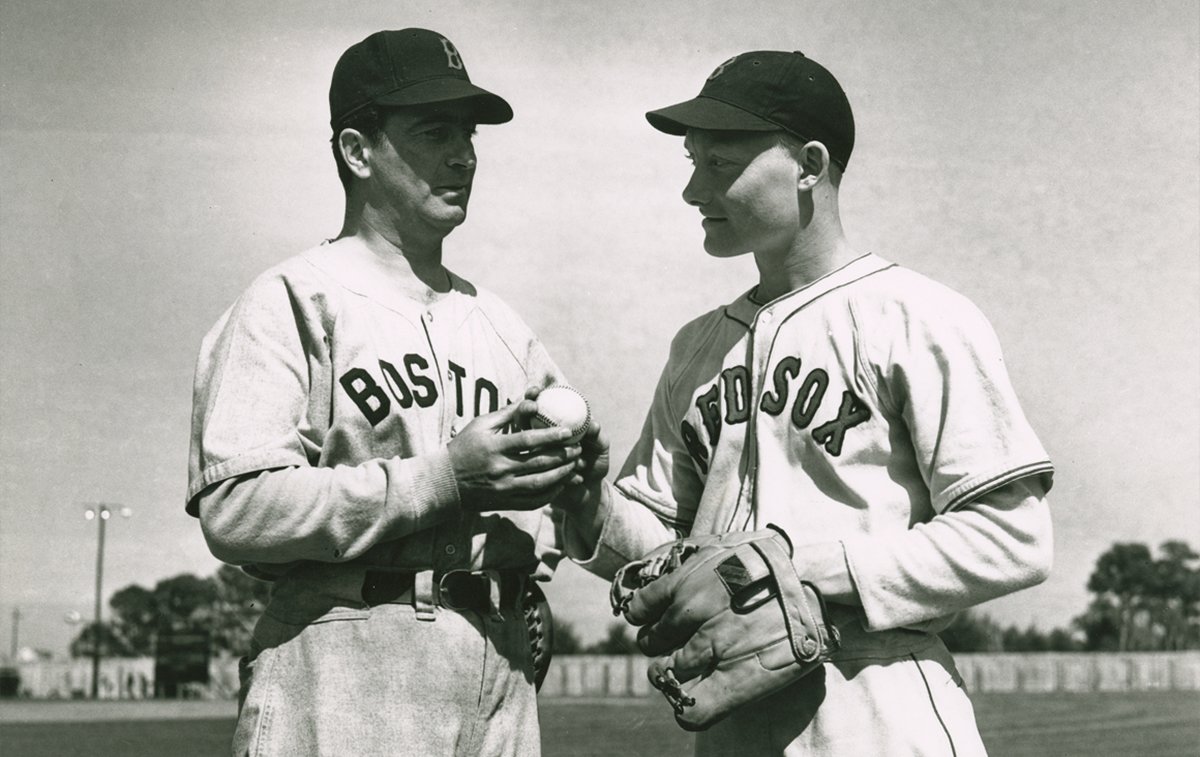

Moe Berg, left, spent 15 seasons in Major League Baseball, mostly as a bullpen catcher, before working as an atomic spy during World War II. Photo courtesy of spybehindhomeplate.org.

A scientist named Flute met a secretive man named Remus in Switzerland in 1944. Inside a laboratory in Zurich, Flute spent hours scribbling atomic chain reactions on a piece of paper. Remus took a pencil and, on the back of the paper, sketched a baseball diamond, informing the Swiss scientist about his favorite American pastime.

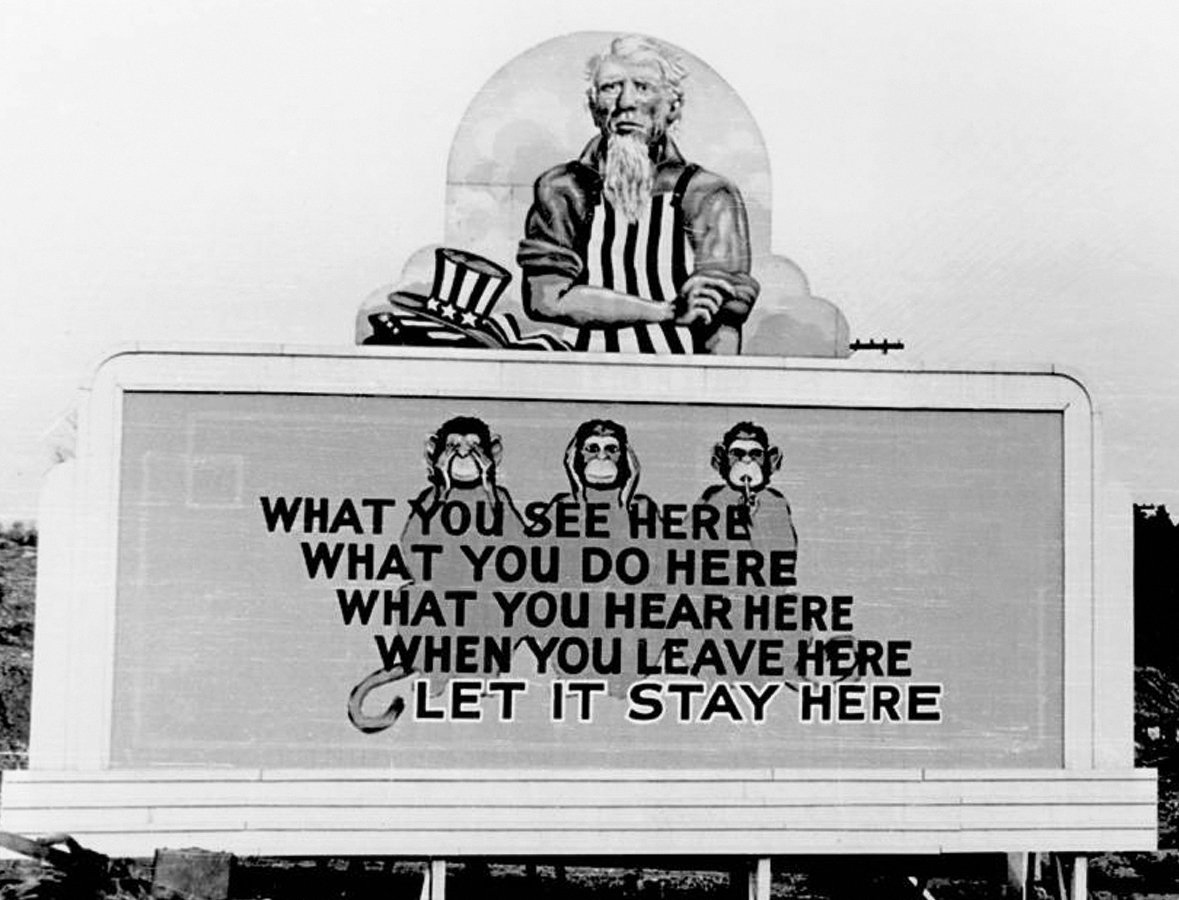

Flute never saw that piece of paper again after handing it over to Remus, the code name for an undercover intelligence officer working for the Office of Strategic Services, the predecessor to the CIA. But Remus moved Flute’s sketching to the upper echelon of the US government, and the information made its way into briefings presented to President Franklin D. Roosevelt at the White House.

Flute was the code name the OSS assigned to Paul Scherrer, the director of physics at the Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich. He was their asset connected to several high-profile scientists the United States suspected of working for the Nazi atomic bomb program.

The real identity of Remus was Morris “Moe” Berg, a former Major League Baseball player who toured with Babe Ruth, a lawyer, and, for most of World War II, one of the most useful spies for the OSS.

The top-secret operation in Austria, called the Alsos Mission, began only a year before in 1943. Soldiers, spies, and scientists deployed across Europe in an effort to uncover evidence of a Nazi nuclear weapons program. The operation led to the capture of German scientists, uranium, and nuclear materials, and thousands of research documents about the development of atomic energy.

Scherrer eventually secured an invitation for Berg — still working as Remus — to dine with Werner Heisenberg, a renowned German physicist and recipient of the Nobel Prize in physics in 1932. After the dinner party, Berg joined Heisenberg on a stroll back to his hotel.

What the German scientist didn’t know was that Berg had instructions to assassinate Heisenberg if he believed the Nazis were close to acquiring a nuclear weapon. And if he were caught, a cyanide pill in his pocket could end his own life in seconds. Berg decided not to carry out the assassination when Heisenberg did not discuss a German bomb during their seemingly friendly stroll.

Berg’s success in Germany traced to his upbringing and classical education and to his easy demeanor that he perfected as a ballplayer. “He could pass for a Broadway actor, a professor, or a banker,” the Des Moines Tribune recalled in 1948.

Before the war, Casey Stengel, the iconic New York Yankees manager, once recalled that Berg was “the strangest man ever to play baseball.” Berg played for 15 seasons, mostly spent crouched in the bullpen swapping stories with relief pitchers. Each morning before going to the ballpark, he purchased multiple newspapers — all written in different languages — using the knowledge in conversations with his teammates.

“Moe was really something in the bullpen,” an anonymous teammate told The Sporting News in 1972, according to Sports Illustrated. “We’d all sit around and listen to him discuss the Greeks, Romans, Japanese, anything. Hell, we didn’t know what he was talking about, but it sure sounded good.”

Dave Harris, a teammate of Berg’s from their days with the Washington Senators, often joked that Berg knew 10 languages, but he couldn’t hit any of them. In the offseason, Berg earned a law degree from Columbia University and took a position on Wall Street, dividing his time between practicing law and baseball. In 1932, Berg traveled to Japan with other ballplayers to start pitching, catching, and hitting clinics for athletes at six universities. There, he became fluent in Japanese.

Two years later, Berg was picked to join Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and other baseball greats on an all-star team that traveled to Tokyo. The tour is widely credited with kick-starting professional baseball in Japan. Berg certainly wasn’t all-star material — but he wasn’t in the country to play baseball.

While there, Berg took to putting on a long black kimono — traditional Japanese attire — and walked to a hospital to visit the daughter of the US ambassador to Japan. She had just given birth, and Berg had picked up flowers for her along the way. However, he bypassed each floor and headed to the roof of the hospital, then the tallest building in the city, and used a Bell & Howell camera from beneath his kimono to make a panoramic film against the wishes of the Japanese. This film was later used for strategic intelligence and viewed by Gen. Jimmy Doolittle’s pilots before their famous raid on Tokyo in April 1942.

In 1939, after five seasons with the Boston Red Sox, Berg hung up his cleats for good. The former pro and well-connected lawyer then stumbled into the foreign service. Nelson Rockefeller, one of his many high-profile friends, secured a job for Berg with the Office of Inter-American Affairs. In this capacity, he traveled through South and Central America in 1942 on a government-sponsored goodwill tour.

When the OSS searched for talent, those who possessed fluency in foreign languages, had overseas travel experience, and had an Ivy League education were considered prime candidates — and Berg hit on all three. He worked overseas assignments with the OSS in Italy, Sweden, and as the atomic spy in Switzerland. In addition to interviewing European scientists, Berg helped confirm that the Germans didn’t have a biological warfare program, and he translated documents and reports sent to Axis glider factories on radar and radio-controlled missiles. He also assisted in the liberation of Antonio Ferri, a prominent Italian aeronautical engineer.

After the war, he received occasional assignments from the recently formed CIA, but his career in espionage was mostly over. In 1947, President Harry S. Truman presented Berg the Presidential Medal of Freedom, then known as the Medal of Freedom, for his “exceptionally meritorious service of high value to the war effort from April 1944 to January 1946.”

However, with the details of his missions still classified, Berg refused to accept the medal, saying it would “embarrass him,” and took his secrets to the grave. Not even his family knew about his OSS service or the medal until after his death in 1972 at the age of 70.

Read Next:

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.