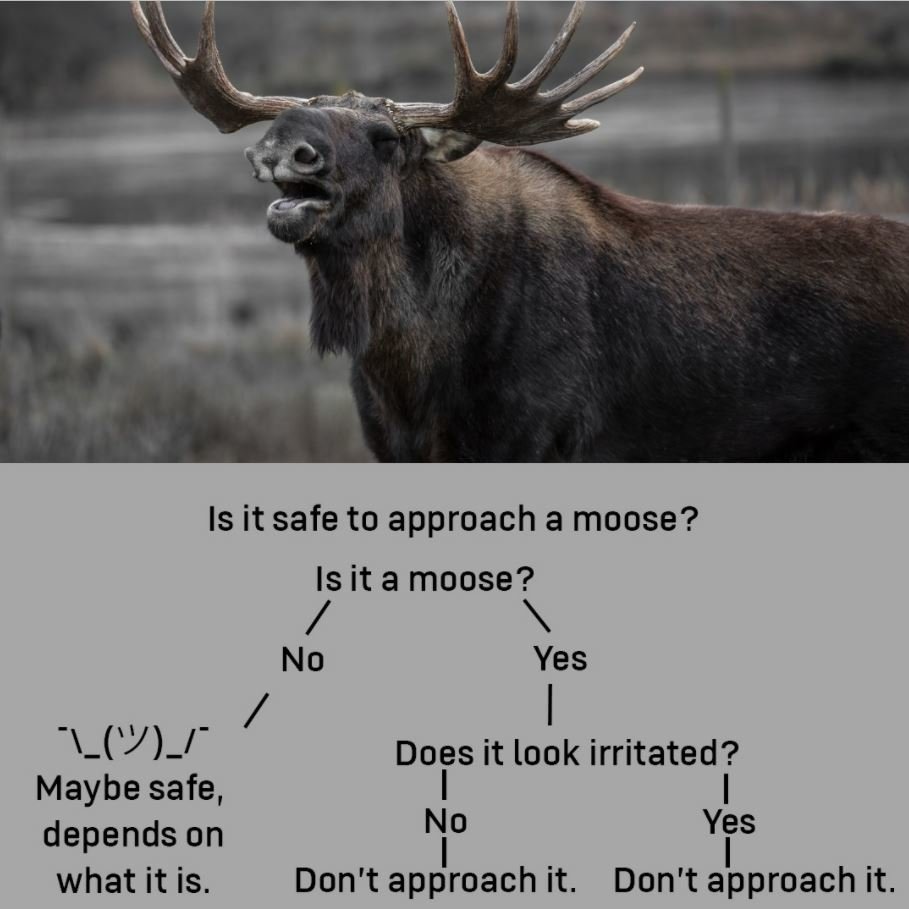

A moose eats a tree on Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson, Alaska, March 20, 2017. Moose are the largest extant species of the deer family, feeding primarily on vegetation. US Air Force photo by Staff Sgt. Westin Warburton.

Prodded by heavy snowfall, Alaska’s hungry moose are on the move, prompting scientists, law enforcement officials, and military leaders to warn everyone to avoid the massive mammals, because a pissed-off moose will straight-up murder your ass.

“What we’ve got going on around Fairbanks is that we got a lot of snow early this year, more than what’s normally here, and it’s deep,” said Tony Hollis, the Fairbanks Area wildlife biologist for the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. “That makes it harder for moose to travel around and feed, so they take to the roads, hard-packed trails, people’s driveways, and they’re stressed, hungry, and they don’t want to get off those paths, which makes them aggressive.”

Hollis said kids walking to and from school in the dark especially need to watch for moose and, if moose are seen, give the herds of herbivores “plenty of space, because they’ll get ornery.”

Those sorts of encounters aren’t good for people or moose. In Fairbanks, most nuisance moose hanging around schools or homes are shot and butchered, with their meat donated to local charities, Hollis said.

Alaska officials estimate there are roughly 175,000 moose in the Last Frontier state. Hunters kill about 7,000 adult moose in Alaska annually, according to the National Park Service.

The moose menace is well known to the University of Alaska Anchorage Police Department. Cops there have a no-tolerance policy on students feeding the beasts.

And if a moose is spotted, everyone is encouraged to call campus dispatch or Anchorage 911 immediately.

On Jan. 11, 1995, an agitated moose roamed the wooded campus with her calf for hours, taunted by students, before charging bystander Myong Chin Ra.

The 71-year-old man tried to flee to the gymnasium but slipped, and the enraged moose stomped him to death.

Today, the university’s police officers warn students to be especially cautious if a moose “stops eating and stares at you,” or lays its ears back and raises its hump hair, or lowers its head and saunters over to you.

Because that moose probably wants to kill you. And if it starts trying to kill you, you should run and hide behind a strong barrier that can withstand its lethal antlers and hooves.

If you don’t make it to a barrier — a bull moose can weigh more than 1,600 pounds and run 30 mph, faster than any Olympic sprinter — police advise you to curl up in a fetal position, shield your head with your arms, and don’t move until the moose decides to leave.

“Use any means you can to protect yourself from an aggressive moose,” the official university moose warning advises.

Moose are frequently spotted near residential quarters on Alaska’s Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson, which is about 7 miles north of the Anchorage campus.

Biologists estimate roughly 1,500 moose live on or near the base, which sprawls across 125 square miles and is home to more than 40,000 service members and their families.

In 2021, JBER officials tracked 125 calls reporting moose. The incidents fall into multiple categories: collision with a vehicle, injured or orphaned animal, or a moose that wanders onto an active range, near a school, or close to people.

So far in 2022, they’ve taken one call about a moose that was on the Glenn Highway. Most reports arrive from JBER’s Cantonment Area, a 7,000-acre spread that includes 1,261 family residence units.

“Most moose calls are not nuisance moose. If they are in a hazardous area, we monitor them and usually route people around them until it’s safe,” said US Air Force Staff Sgt. Michael Pfeiffer, a base spokesperson, in an email to Coffee or Die Magazine.

State and federal officials know that Alaska’s moose can pose problems for people, aircraft, and vehicles.

Since 1990, the Federal Aviation Administration has recorded six incidents in Alaska when moose tangled with planes, including at the bustling Ted Stevens Anchorage International Airport. Five of those aircraft suffered extensive damage.

The Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities counts about 765 collisions involving vehicles and animals annually, 85% of which are linked to moose.

The typical crash incurs $34,000 in vehicle and medical costs.

“I’ve unfortunately encountered dangerous moose quite a few times,” Alaska Department of Fish and Game’s Hollis said. “They can be real aggressive. They’ll kick and stomp.”

Read Next:

Carl Prine is a former senior editor at Coffee or Die Magazine. He has worked at Navy Times, The San Diego Union-Tribune, and Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. He served in the Marine Corps and the Pennsylvania Army National Guard. His awards include the Joseph Galloway Award for Distinguished Reporting on the military, a first prize from Investigative Reporters & Editors, and the Combat Infantryman Badge.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.