Nineteen servicemen have been awarded the Medal of Honor twice. Fourteen have been awarded the medal for two separate events. The U.S. Navy is the most awarded branch with eight sailors, some receiving the award not for combat heroism but life-saving actions. Added to that, the Medal of Honor was initially confined to only enlisted Navy sailors and U.S. Marines; U.S. Army officers were granted eligibility in 1863, and then it was open to everyone in the military. The most recent double Medal of Honor recipient earned the medal almost exactly 100 years ago in 1918 during World War I.

Regulations for the Medal of Honor today do not allow for two awards to be given for the same action. Those that were recognized for their peacetime heroism now are awarded the Soldier’s Medal (Army) or the Navy and Marine Corps Medal. Remarkably, of the 19 veterans to earn the Medal twice, five of them were born in Ireland, which has a strong representation with 258 Irish-born U.S. service members having earned the medal.

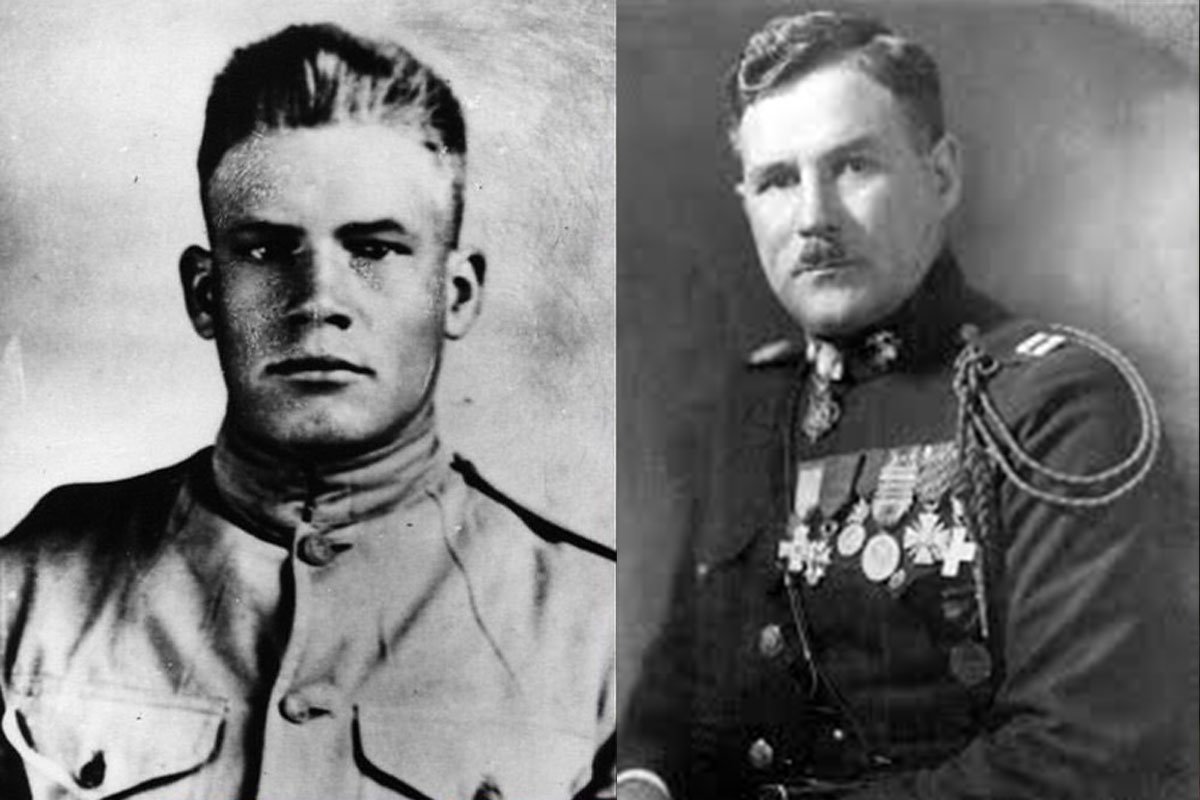

Frank Baldwin, U.S. Army

Frank Baldwin, a career U.S. Army officer, was recommended for the Medal of Honor three times while fighting two different adversaries and practically didn’t have an off-day from soldiering for 35 years across the American West! He served under George Armstrong Custer and alongside the legendary lawman “Bat” Masterson. They were living legends in a time when turmoil between the nation and American Indian tribes could make or break the direction of our country’s future. The 1864 Battle of Peachtree saw the captain leading “his company in a countercharge, under a galling fire ahead of his own men, and singly entered the enemy’s line, capturing and bringing back two commissioned officers, fully armed, besides a guidon of a Georgia regiment.”

Harper’s Weekly sat down with Masterson and discussed their heroic campaign during the winter of 1868 to 1869. He spoke of then-Lieutenant Baldwin serving alongside him and how he was responsible for leading a company of Custer’s scouts in 7 degrees below zero weather and two feet of snow into Indian Territory on Thanksgiving Day. Baldwin also served under notorious Indian fighter Nelson A. Miles in 1874 and was responsible for rooting the violence from the Cheyenne, Kiowa, Arapahoe, and Comanche tribes. When his unit received word that two women were captured by a superior force of Indians, Baldwin led a two-company-strong rescue to save them. For these actions, he was awarded his second Medal of Honor.

Baldwin retired after 40 years of service and was later recalled to the National Guard to help mentor soldiers entering World War I. He spent his final days in Colorado with his wife and daughter.

Smedley Butler, U.S. Marine Corps

Smedley Butler may be the best-known double Medal of Honor recipient and one of the most popular military generals in U.S. history. Butler served 33 years in the Marine Corps and had a role in the Spanish-American War in Cuba, the Philippine-American War in Manila, the Boxer Rebellion in China, the Banana Wars in the Carribean, the Mexican Revolution, and World War I. Butler’s first Medal of Honor was earned during the Mexican Revolution when the then-major fought block to block in the streets of Vera Cruz to rid the city of the resistance. His second award occurred a year later in 1915 when his Marines engaged in hand-to-hand combat with the Cacos resistance, a lower society of miscreants who formed a gang to wreak havoc in Haiti.

His wartime heroics became legendary, and he is one of the most recognized Marines of all time. Butler also introduced the Marine Corps’ first unofficial mascot, a bulldog named Jiggs, in 1922. It birthed a tradition, with all following mascots being awarded a service contract of “life” with duties of “sit, stay, and lie down.” “The Fighting Quaker,” which was a nickname for the Pennsylvania native, wasn’t afraid to speak his mind, and Butler wrote several short stories in “War is a Racket” discussing how those in power profit from war.

Although he only served as the director of public safety in Philadelphia for one year, his impact helped establish police reform in the city, which was full of corrupt public officials. He was labeled as being “incorruptible” and formed his own ragtag group of bandit-chasing police. The squads patrolled in armored cars with radios and carried sawed-off shotguns. The 1920s were fret with speakeasies, organized crime, and untrustworthy politicians. Butler later said, “Cleaning up Philadelphia’s vice is worse than any battle I was ever in.” He died in 1940 as one of the most revered military generals of all time.

John Laver Mather Cooper, U.S. Navy

Not much is known about John Laver Mather, who also went by the alias John Cooper. He was born in Dublin, Ireland, in 1832, and served as a coxswain in the U.S. Navy aboard the USS Brooklyn, where he was involved in the Battle of Mobile Bay. He and 13 other Irish-Americans were awarded the Medal of Honor for their actions that day. On Aug. 5, 1864, Cooper fought with distinction despite his ship being shot to pieces and his men lying dead on the ship’s deck. The rebel ram Tennessee surrendered, and Cooper shifted his focus to coastal batteries at Fort Morgan.

The second action that Cooper received the award was while serving as a quartermaster under Rear Admiral Thatcher. On April 26, 1865, an accidental fire had sprouted near a stockpile of shells. At risk of the shells exploding, Cooper rushed into the fire, grabbed a wounded soldier, heaved him over his shoulder, and ran outside, saving the soldier from certain death.

Louis Cukela, U.S. Army and U.S. Marine Corps

Louis Cukela was a two-branch vet, having enlisted in the U.S. Army a year after he emigrated from Croatia in 1913. He served for four years before he reenlisted into the Marine Corps when the U.S. got involved in World War I. In France’s Forest de Retz, Cukela crawled beyond friendly lines to charge a machine gun nest by himself. He single-handedly disabled it by bayoneting the crew one by one in hand-to-hand fighting. He then grabbed their hand grenades and lobbed them on top of remaining positions. In the end, he captured four soldiers and two undamaged machine guns.

For this action, both the Army and Navy awarded him the Medal of Honor; he also received valor awards from Yugoslavia and France. Cukela was wounded twice during the war, though not seriously enough to warrant a Purple Heart distinction. He continued to serve and received a field commission as a mustang officer (former enlisted). He later deployed to Haiti; Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic; and China, as well as serving in shore-based assignments in the States.

Cukela retired as a major in 1940 but was recalled during World War II for shore duties. After almost 32 years of service, Cukela officially ended his historic career with a chest full of medals.

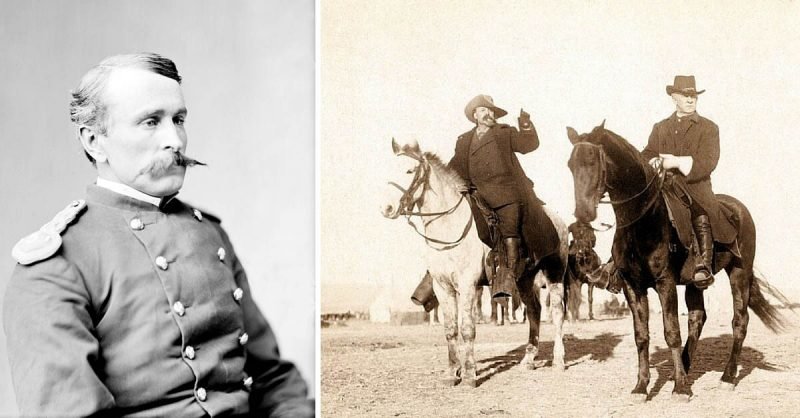

Thomas Custer, U.S. Army

Thomas “Tom” Custer was the first dual Medal of Honor recipient, and the only American Civil War veteran to achieve such a feat. He is often called “the other Custer” as he is the younger brother of George Armstrong Custer. On Sept. 2, 1861, at just 16 years old, Tom needed his parent’s approval to enlist into the 21st Ohio Infantry.

Flag bearers on the battlefield were critical in relaying communications by signaling their troops on what to do in the middle of chaos. To capture a flag meant facing extraordinary peril and having extreme courage. While at the Namozine Church, Tom Custer overtook the 2nd North Carolina Cavalry flag by jumping over an obstacle on his horse and yanking the flag from the bearers hands. Eleven soldiers and three officers surrendered on the spot.

Three days later, Custer repeated the feat at Sailor’s Creek, this time armed with only a pistol. He was wounded in the face by the rebels and was evacuated on horse from the Army of the Potomac’s 3rd Cavalry Division. Custer was wounded a second time during the Indian Wars’ 1868 Wichita Campaign and served during the expeditions in Yellowstone and the Black Hills.

The Custer brothers led a hard life and were eventually slain together at what became known as Custer’s Final Stand during the Little Bighorn Campaign in 1876.

Daniel Daly, U.S. Marine Corps

Daniel Daly’s reputation is such that Major General John Lejune once called him “the greatest of all leathernecks” and “the [most] outstanding Marine of all time.” Smedley Butler, who also appears on this list, once said Daly was “the fightingest Marine I ever knew” and “it was an object lesson to have served with him.” High praise from two legendary Marines

Daly stood just 5-foot-6 and weighed 132 pounds. The Long Island native was a newsboy and amatuer boxer before he became a Marine. During the Boxer Rebellion in China, Daly personally positioned himself alone along the Tarter Wall despite being exposed to sniper fire and other attacks. His small contingent of Marines helped protect the diplomatic personnel from being overrun. For this action, he was awarded his first Medal of Honor.

He would earn his second nearly 15 years later while fighting the Cacos in Haiti. His second award citation reads, “On 22 October 1915. Gunnery Sergeant Daly was one of the companies to leave Fort Liberte, Haiti, for a six-day reconnaissance. After dark on the evening of 24 October, while crossing the river in a deep ravine, the detachment was suddenly fired upon from three sides by about 400 Cacos concealed in bushes about 100 yards from the fort. The Marine detachment fought its way forward to a good position, which it maintained during the night, although subjected to a continuous fire from the Cacos. At daybreak the Marines, in three squads, advanced in three different directions, surprising and scattering the Cacos in all directions. Gunnery Sergeant Daly fought with exceptional gallantry against heavy odds throughout this action.”

Daly also is known for his legendary battle cry — “Come on you sons of bitches, do you want to live forever?” — which has become synonymous with his heroism. During World War I, 44-year-old Daly led an assault in which he single-handedly captured a machine gun nest armed with only a pistol and several hand grenades. He was wounded three times and was recommended for his third Medal of Honor; however, due to bureaucratic red tape, it was downgraded to the Distinguished Service Cross. Daly is still remembered as one of the greatest U.S. Marine Corps officers to ever live.

Henry Hogan, U.S. Army

Henry Hogan was awarded his two Medal of Honors while assigned to the same unit: Company G, 5th US Infantry. His first medal citation is incredibly vague. The Ireland-native served at Cedar Creek, Montana, from October 1876 to January 1877, where he was recognized for “Gallantry in actions.” The Battle of Cedar Creek called for the removal of Confederate soldiers in the Shenandoah Valley and the destruction of food and supply routes.

Hogan’s second action occurred at Bear Paw Mountain, Montana. Hogan carried a severely wounded Lieutenant Henry Romeyn off the battlefield despite heavy gunfire. Romeyn’s report said that Hogan “carried me off the field” and “whose action probably enabled me to live.” Romeyn was awarded the Medal of Honor for his action in leading an assault within close distance of enemy forces until he was wounded. Hogan is one of only three Medal of Honor recipients who saved the life of another Medal of Honor recipient (John Coleman and Mike Thornton being the other two).

Ernest A. Janson (AKA Charles Hoffman), U.S. Army and U.S. Marine Corps

What did the soldier Ernest Janson and the Marine Charles Hoffman have in common? Quite a bit considering they were the same person. Hoffman served under the name Ernest Janson in the U.S. Army for 10 years prior to the start of World War I. By the time of his action in France during the Battle of Belleau Wood — working under his assumed alias Charles Hoffman — he was a highly respected 39-year-old Gunnery Sergeant.

Hoffman was a part of the 5th Marine Regiment attached to the Army’s 2nd Division. Near Belleau Wood on Hill 142 located about 30 miles from Paris, Janson led a one-man counterattack against a dozen German soldiers. In the surprise attack, Hoffman rushed forward, stuck his bayonet into two of them, and caused the remainder of the soldiers to flee the area. For this action, he was awarded the Medal of Honor by both the Army and the Navy. After the war, he became Ernest Janson again and continued to serve until he retired as a sergeant major at the age of 48.

John J. Kelly, U.S. Marine Corps

John Joseph Kelly was a Chicago native who earned the Medal of Honor from both the Army and the Navy while he was still a teenager. Kelly fought in Chateau Thierry, St. Mihiel, Blanc Mont, and the Meuse-Argonne during World War I. At Blanc Mont Ridge, he sprinted 100 yards into no man’s land through an artillery barrage to seize an enemy machine gun nest.

Kelly killed the crew and captured eight prisoners of war. General John J. Pershing personally draped the medal around his neck. He returned to Chicago a national hero.

John King, U.S. Navy

Chief Watertender John King was decorated for two separate actions both aboard naval vessels that experienced catastrophic accidents. King lived in a small market town called Ballinrobe in western Ireland. A son of a farmer, King emigrated to the U.S. when he was 24 and enlisted in the U.S. Navy when he was 31. Research from the Garland County Historical Society uncovered King’s firsthand account of his action during a boiler explosion on the USS Vicksburg (Gunboat No. 11).

On May 29, 1901, King said he “shut off the main stop of the boiler and smothered it up with blankets and towels.” His second recommendation for the Medal of Honor came aboard the USS Salem, the Navy’s first turbine-engine warship.

King stated, “explosion in a boiler [which] carried away the tube and 12 men in the fire-room stood in danger of being scalded to death. I was in the fire-room, and turned on the blowers full force. There was 310 pounds of steam on at the time. I was badly scalded on the arms, but went back to the fire-room and stayed until the engineer of the watch found me, and sent me to sick bay. We got all the men out of the fire-room and no one was injured.”

King was 47 years old and continued to serve until he was discharged in 1916. He was briefly recalled during World War I. He and his wife resettled in western Ireland not far from where he grew up. A life-sized bronze statue sits in his hometown, and the U.S. Navy honored him with a now decommissioned guided-missile destroyer.

Matej Kocak, U.S. Army and U.S. Marine Corps

Matej Kocak was born in Egbell, Kingdom of Hungary (now Slovakia), and he immigrated to the U.S. in 1906. Kocak served in both the Marine Corps and the Army. He fought bandits in the Dominican Republic and also participated in missions throughout France during World War I.

On July 18, 1918, Kocak was awarded the Medal of Honor by both the Army and the Navy for the same action while serving with 66th Company, 5th Regiment, 2nd Division. His citation reads: “When the advance of his battalion was checked by a hidden machine gun nest, he went forward alone, unprotected by covering fire from his own men, and worked in between the German positions in the face of fire from enemy covering detachments. Locating the machine gun nest, he rushed it and with his bayonet drove off the crew. Shortly after this he organized 25 French colonial soldiers who had become separated from their company and led them in attacking another machine gun nest, which was also put out of action.”

In October 1918, Kocak was killed in action in the Argonne Forest. He was 36 years old.

John Lafferty, U.S. Navy

This Navy sailor served under two names: John Lafferty and John Laverty. His first citation reads, “[F]or extraordinary heroism in action while serving on board the U.S.S. Wyalusing. Fireman Lafferty participated in a plan to destroy the rebel ram Albemarle in Roanoke River, North Carolina, 25 May 1864. Volunteering for the hazardous mission, Fireman Lafferty participated in the transfer of two torpedoes across an island swamp and then served as sentry to keep guard of clothes and arms left by other members of the party. After being rejoined by others of the party who had been discovered before the plan could be completed, Lafferty succeeded in returning to the mothership after spending 24 hours of discomfort in the rain and swamp.”

His second award was earned in 1881 while aboard the USS Alaska at Callao Bay, Peru. The Alaska was a wooden-hulled vessel, and if a fire onboard spread, it could lead to disaster. A stop-valve chamber had caught fire in the boiler room. Laverty was the ship’s fireman and helped extinguish the flames.

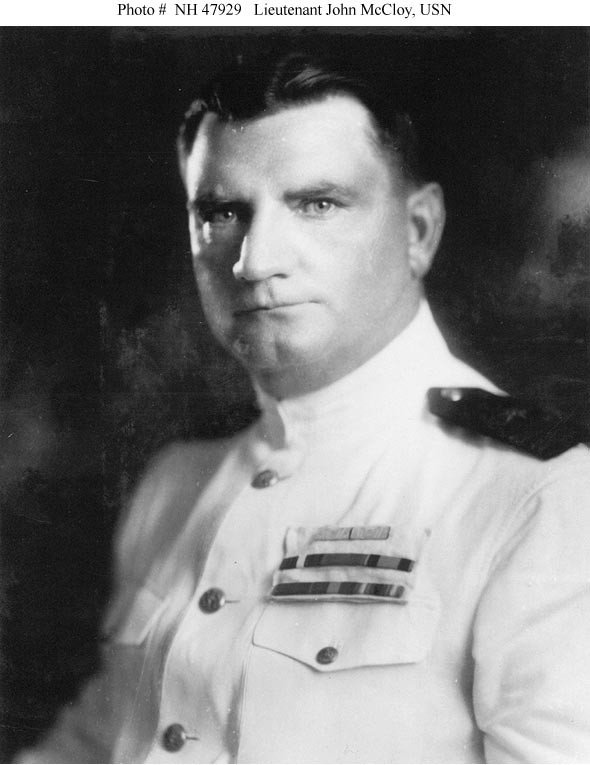

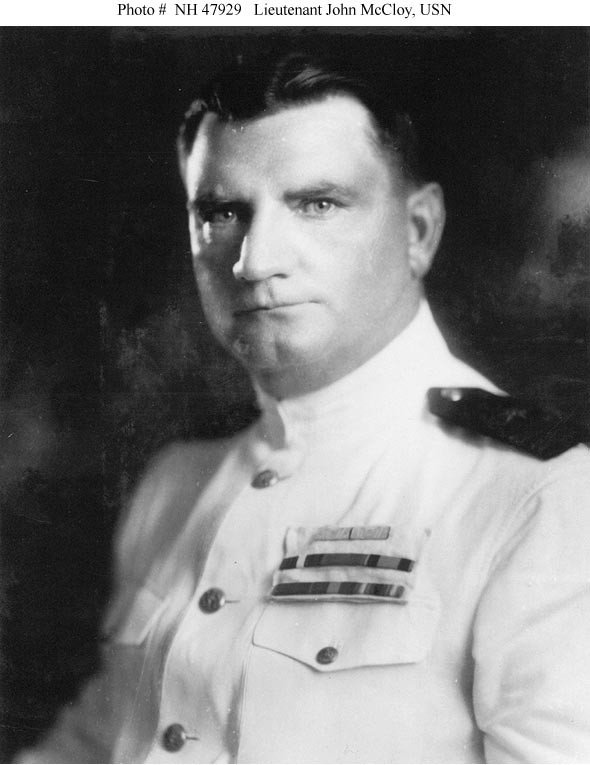

John McCloy, U.S. Navy

John McCloy is a veteran of the Spanish-American War, the Boxer Rebellion, the occupation of Vera Cruz in Mexico, and World War I. His first award came while serving in the Boxer Rebellion, where he distinguished himself in the presence of the enemy on June 13, 20, 21, and 22, 1900.

The New York native’s second award came 14 years later. According to his citation, “For heroism in leading 3 picket launches along Vera Cruz sea front, drawing Mexican fire and enabling cruisers to save our men on shore, 22 April 1914. Though wounded [through his thigh], he gallantly remained at his post.”

McCloy’s boyhood dream was to be a sailor, and he joined the Merchant Marines when he was 15 years old. In addition to his two Medals of Honor, McCloy was also awarded the Navy Cross during World War I for operating a minesweeper through the North Sea, and the state of New York recognized his peacetime heroism while saving an entire schooner from shipwreck during a hurricane off the Florida Keys. He retired in 1928 as a lieutenant after 20 years of honorable service.

Patrick Mullen, U.S. Navy

Irish-born Patrick Mullen earned his first Medal of Honor during a boating expedition up Mattox Creek on March 17, 1865. Mullen was engaged with enemy rebels, and to provide assistance to his commanding officer, Mullen successfully loaded a howitzer while lying on his back and fired it into a crowd of soldiers, dispersing those who had survived the assault.

Mullen’s second award came from his action on May 1, 1865. Mullen recognized an officer couldn’t keep his head above the water and was starting to drown. With quick responsiveness, Mullen hurled his body into the water to rescue his shipmate. He retrieved him and brought him onto the deck of the USS Don, saving his life.

Ludwig Andres Olsen, U.S. Navy

Ludwig Andres Olsen was born in Oslo, Norway, in 1845. Under an alias, he dropped his Norwegian name and adopted Louis Williams as his new identity. While aboard the USS Lackawanna off the coast of Honolulu, Hawaii, in March 1883, he dove off the deck to save Thomas Moran, a landsman who was drowning.

Only a year later, in Callao, Peru, Olsen again jumped into the water to save a drowning shipmate. William Cruise had fallen overboard on June 13, 1884. Olsen, along with Issac L. Fasseur (also awarded the MOH), was in the right place at the right time. Olsen served for a total of 16 years and is one of the few to earn the award twice for non-combat actions.

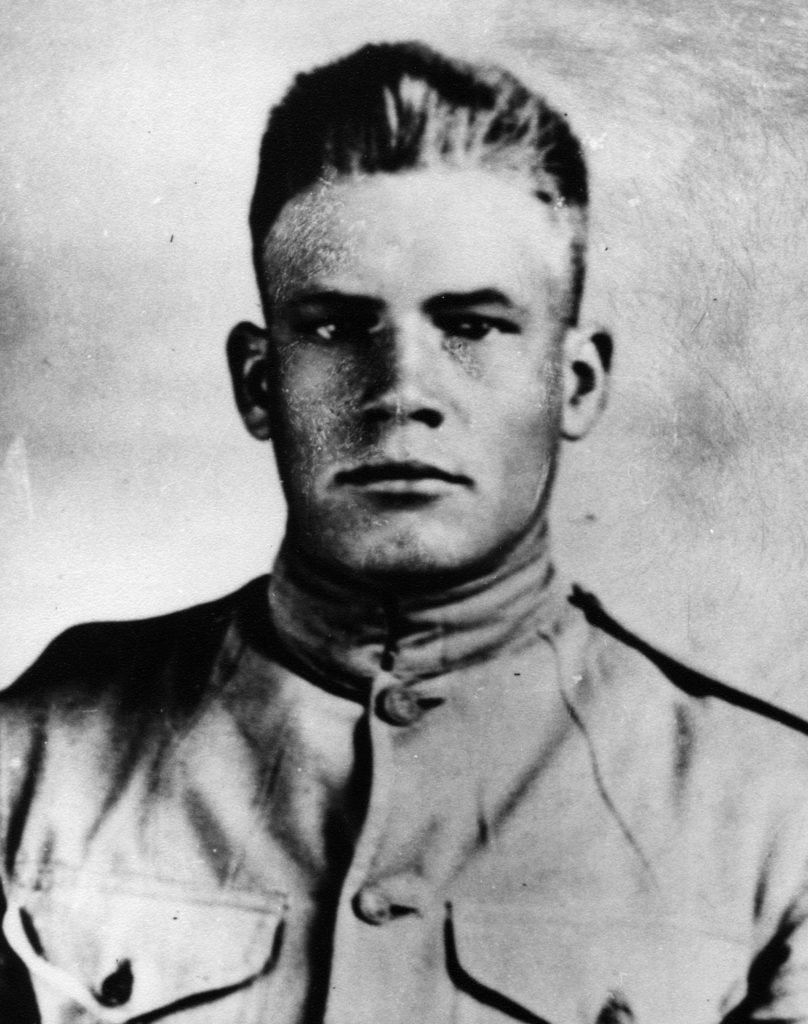

John H. Pruitt, U.S. Marine Corps

John Pruitt was listed on General John J. Pershing’s 100 — 100 names with 100 stories of valor that provided perspective to the average U.S. citizen about what their brothers, husbands, and sons faced during World War I. Pruitt was born in Fayetteville, Arkansas, and was a veteran of the 6th Marine Regiment. He served in the Battles of Belleau Wood, Chateau-Thierry, and Blanc Mont Ridge. He received three Silver Stars before performing the actions that would earn him the highest U.S. military medal for valor. His first came when he and his squad captured an enemy machine gun in September 1917. Pruitt’s second and third occurred between October 1st and 10th at Blanc Mont Ridge.

The day before his 22nd birthday, Pruitt would earn the Medal of Honor posthumously from both the Army and the Navy for the same action. His citation from the Army read: “Pruitt single-handedly attacked two machineguns, capturing them and killing two of the enemy. He then captured 40 prisoners in a dugout nearby. This gallant Marine was killed soon afterward by shellfire while he was sniping at the enemy.”

Robert Augustus Sweeney, U.S. Navy

Robert August Sweeney is the only African-American to receive the Medal of Honor twice. There are no images of him, but his deed aboard two naval vessels will never be forgotten. Born in 1853 in Montserrat, a French island in the West Indies, Sweeney immigrated to the United States and enlisted in the U.S. Navy in New Jersey in 1873. His first Medal of Honor action occurred on Sept. 17, 1881, in Hampton Roads, Virginia, when a sailor aboard the USS Kearsarge fell overboard. The tide pulled the sailor farther away from the Kearsarge and waves flowed over his head, but that didn’t stop Sweeney from diving overboard to save his shipmate. When Sweeney finally reached the sailor, he held onto him for an estimated half an hour before the vessel could lift them aboard.

His second award also occurred stateside and for a similar action. While the USS Yantic had a gangplank between the USS Jamestown in the New York Navy Yard, sailors had to watch their step in order to cross. A cabin boy named A.A. George missed his step and fell into the water. Both Sweeney and a USS Jamestown sailor named J.W. Norris leapt after the boy and ultimately saved him. Sweeney and Norris were both awarded the Medal of Honor for their peacetime actions.

Albert Weisbogel, U.S. Navy

Albert Weisbogel was born in New Orleans in 1844 and served in the U.S. Navy. He was assigned to three different ships over his career, including the USS Juniata, a traditional Navy sloop of war, and the USS Benicia and the USS Plymouth, which were screw loops — sloop of wars with a propellor — from 1874 to 1886. Weisbogel earned both his Medal of Honor awards for peacetime actions. On Jan. 11, 1876, while aboard the USS Benicia, a suicidal Marine jumped overboard, and Weisbogel went in after him to prevent his “fit of insanity.”

Two years later, Weisbogel jumped into the water near Kingston, Jamaica, to save a drowning shipmate, this time from the USS Jaunita. Today, peacetime actions in the U.S. Navy warrant the Navy and Marine Corps Medal in lieu of the Medal of Honor.

William Wilson, U.S. Army

There are two William Wilsons that earned the Medal of Honor at least once. William Othello Wilson served with the famed Buffalo Soldiers during the Sioux Campaign in 1890. William Wilson of Philadelphia earned the Medal of Honor twice for two separate actions during the Indian Wars.

An interview in 1890 with The Sunday Herald, Wilson said, “In the year 1872 I was a sergeant in Troop I, Fourth Cavalry, stationed at Fort Concho, Tex., and was ordered with a detail of one corporal and ten privates in pursuit of a raiding party of Indians who had stolen stock in the neighborhood of the post. On the morning of March 11 I started. After striking their trail five miles from the post I followed it all day and the greater part of the night on a trot and gallop, halting thirty minutes in the afternoon to eat lunch, camping at night on the trail in the mountains. In the morning we started again, the trail leading toward the Colorado River, and after traveling some time I turned in to the river for the purpose of cooking breakfast, sending one man on lookout. We had hardly got our cups on the fire before the lookout was observed coming into camp on a run.

“We immediately upset our water, put out the fire, and led the horses in. By this time the lookout had reported Indians a short way up the river. I mounted my detail and moved up in the direction indicated, and as we were about crossing a small stream leading into the main river we were greeted by a shot and then by a straggling volley. We charged their position, going through their camp, and, taking my position on a small eminence in their rear, I dismounted my men and went to work. In about two hours I had the entire outfit, burnt their saddles and camping outfit, capturing their stock and bringing in one prisoner, killing two, and wounding three, without the loss of a man or horse in my detachment. We returned to Fort Concho, where we arrived on the morning of the 13th, having ridden 120 miles in fifty-four hours. My conduct was brought to the notice of the Government, and I was awarded Medal No. 1. That prisoner I brought in was questioned, and gave information in relation to camps of Indians on the Staked Plains, and three columns were sent to operate against them.”

His second award came a few months later in September while leading the U.S. Army’s 4th Cavalry in the Battle of the North Fork of the Red River. He and his men killed 100 tribesman, captured more than 100 survivors, seized an estimated 3,000 ponies, and overtook a series of villages. He continued service, wrote often about his experiences, and even did a stint as a railway superintendent. Wilson died of stomach cancer in 1895.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.