An American Special Forces NCO launches a 120mm mortar round during a fire mission in eastern Afghanistan. Photo by Marty Skovlund Jr./Coffee or Die Magazine.

Wars are as culturally defining for a nation as its pop culture and politics. Each generation of war veterans breeds a new generation of writers who are willing to expose their scars and bleed them onto the page. The act itself violates a warrior-culture taboo: breaking the quiet professionalism ethos.

The Global War on Terrorism began when the twin towers fell on Sept. 11, 2001, and it continues to this day. It has been operating in the background of American life for the past two decades. Over 2.77 million men and women have deployed in direct support of it, creating a new generation of veterans and war correspondents who have seen fit to share their experience and knowledge through literature. What follows are seven of the most defining books of the Global War on Terror.

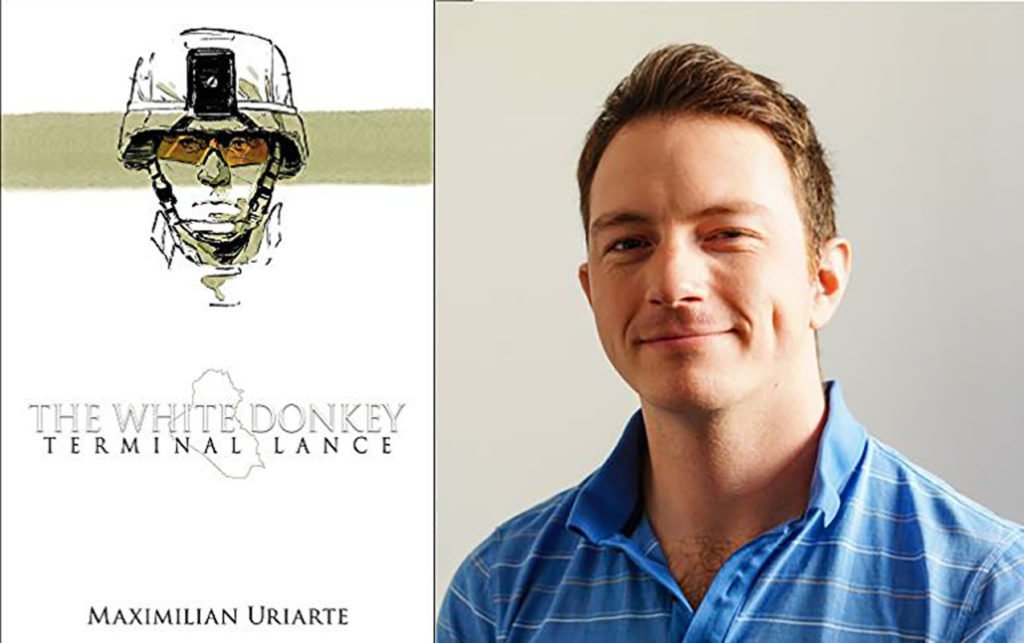

“The White Donkey” by Maximilian Uriarte

A beautifully illustrated and written graphic novel by the creator of the “Terminal Lance” comic strip, “The White Donkey” follows the story of Lance Corporal Abraham “Abe” Belatzeko, who joins the U.S. Marine Corps in the later stages of the Iraq War. In search of something he can’t explain, he trudges through the mundanity and physical discomfort of being a boot infantryman. Abe yearns for the opportunity to prove himself as a man and find enlightenment through spilling the blood of the enemy. But then the irreversible horrors of combat show him that war ain’t as glamorous as it’s portrayed in the movies.

When Abe returns home, the demons that were spurred from his experiences and regrets on that deployment cause him to disassociate from his fellow Marines, friends, and family. Uriate’s attention to detail in his realistic imagery is striking. He captures the essence of mid-2000s military and civilian life: The flip phones. The protests. The general population’s misunderstanding of the Iraq war. Through the story of this single Marine, “The White Donkey” takes us back to a war that has almost been forgotten.

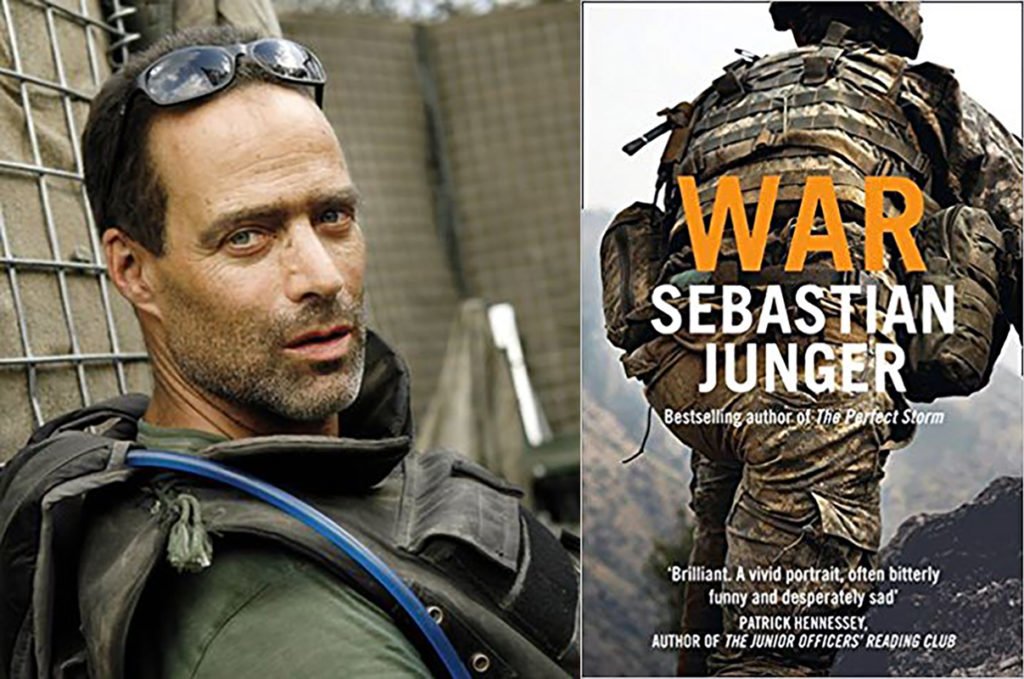

“War” by Sebastian Junger

What’s it like at the edge of the world? “War” follows the paratroopers from the U.S. Army’s 173rd Airborne Brigade as they establish a forward operating base in the Korengal Valley in Afghanistan. The valley is a route used by the Taliban to smuggle in fresh troops and supplies for their Jihad against the Americans. The area has been left alone in the past because it was too remote to conquer, too poor to intimidate, and too autonomous to buy off.

Private First Class Juan Restrepo is amongst the first casualties of the platoon on this deployment. His death leaves such a rift that they name their FOB after him. Aside from the occasional resupply helicopters and their sister platoon in the valley, the men are completely cut off from the rest of the world, deep in hostile territory. Facing the ever-present threat of being overrun by a determined and skillful enemy, they eagerly await their next firefight, as the boredom and repetition of war sets in.

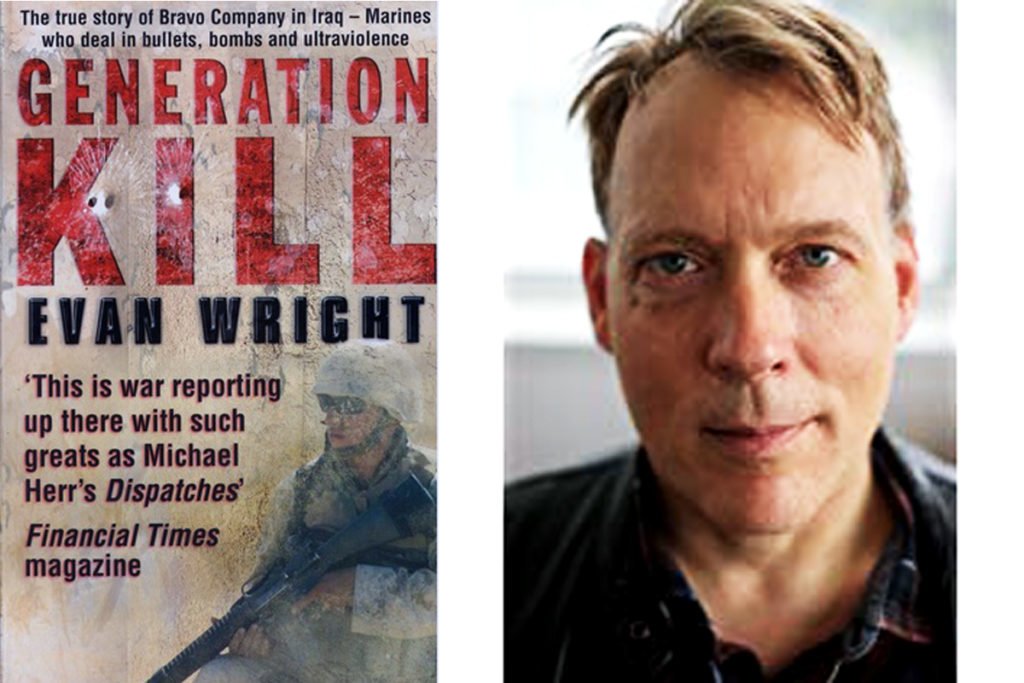

“Generation Kill” by Evan Wright

In March 2003, on the dawn of the invasion of Iraq, Evan Wright (a reporter from Rolling Stone magazine) joined the Marines of 1st Reconnaissance Battalion. Taking a passenger seat in the lead Humvee full of colorful Marines, Wright followed them on a road trip to war. What makes this book so captivating is not the war itself, but rather how Wright was able to capture the personalities of the Marines he was with.

The dialogue between Sergeant Colbert and Corporal Person are masterful examples of how humor is amplified by and transcends the chaos of war. The mean-street-influenced philosophy of Sergeant Espera offers surprising insight into human nature and how the white overloads really control the people. Trombley’s cavalier eagerness to get his first kill is strangely relatable.

Wright also captures many of the shortcomings of the chain of command, from overly strict enforcement of the grooming standards to its recklessness in abandoning a supply truck carrying the colors that their battalion had taken into combat since Vietnam. In a vivid scene, the company commander, known as “Encino Man,” attempts to call in artillery fire that is danger close to his men, only to be stopped by his subordinates because it may get them killed. The internal strife and politics alongside the basic discomfort of life in a combat zone wears thin on the morale of the unit.

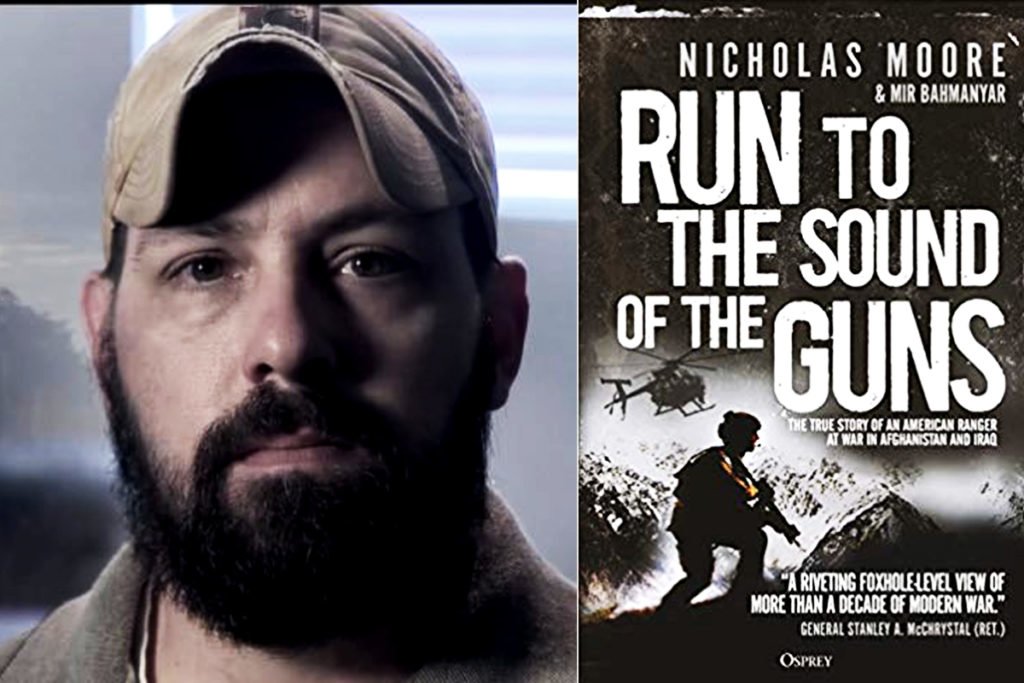

“Run to the Sound of the Guns: The True Story of an American Ranger at War in Afghanistan and Iraq” by Nicholas Moore

The true, firsthand account of Sergeant First Class Nicholas Moore, who has spent more than a decade preparing for and going to war with the U.S. Army’s 75th Ranger Regiment. When 9/11 occurred, Moore was a young private going through Ranger School. He was not scared of going to war — he was afraid of missing out on the action. Everyone thought that the war in Afghanistan would end quickly, similar to the more recent conflicts in Grenada, Panama, and Somalia. Little did he know that he’d be taking part in some of the war’s most famous events, such as rescuing Jessica Lynch and Operation Red Wings, the latter involving the search for a U.S. Navy SEAL element that had been pinned down.

The foul-mouthed nature of Rangers is softened considerably in Moore’s account, which is due to the fact that Moore is a family man who wanted to set a positive example for his children. However, he has no qualms with friendly criticism of his fellow special operations units. In these pages, you’ll catch a glimpse of the intense operation tempo of the 75th Ranger Regiment. Moore’s personal and professional development from lower-enlisted to senior noncommissioned officer is in direct parallel to the changes the GWOT and Ranger Regiment underwent.

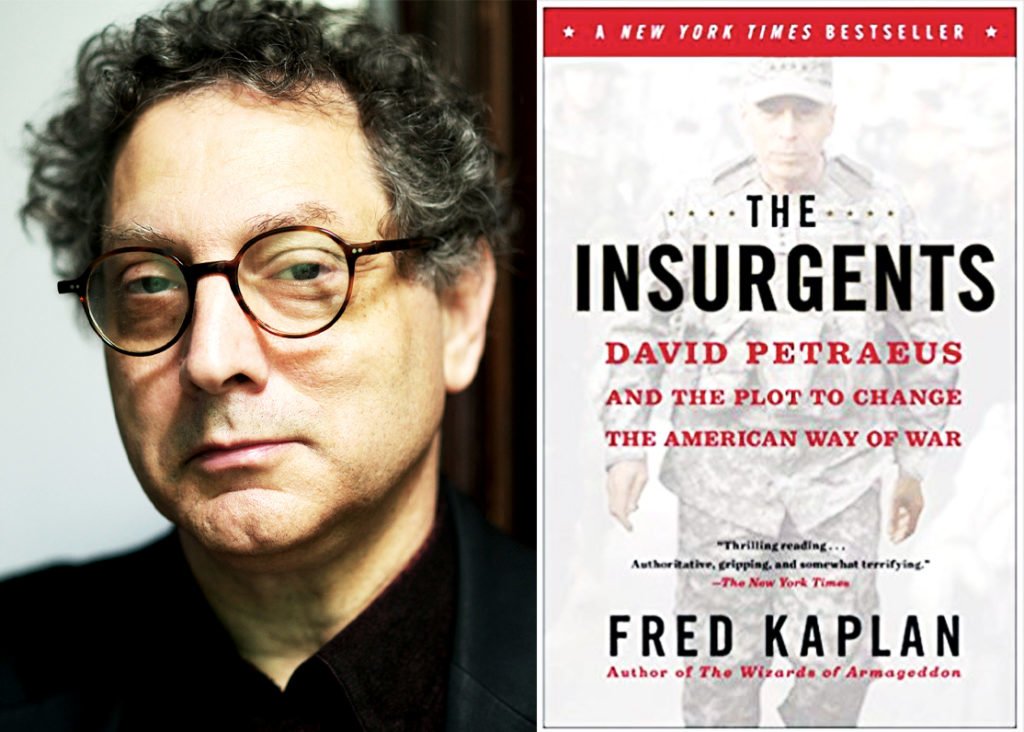

“The Insurgents: David Petraeus and the Plot to Change the American Way of War” by Fred Kaplan

The post-Vietnam War American military had adopted a “never again” philosophy toward fighting an indigenous guerilla force. The hard lessons it acquired in Vietnam through bloodshed were tossed aside as it returned to the Cold War-era of mass manpower military in a superpower conflict like World War II. The collapse of the Soviet Union and the destruction of Saddam Hussein’s vast tank columns during the first Gulf War left the U.S. the only super left on the planet. When the invasion of Iraq in 2003 ousted Hussein from power, a power vacuum occurred as the civil service administration run by the Ba’ath Party also collapsed.

General David Petraus, commander of the 101st Airborne Division during the invasion, found that he was fighting off an insurgency in Mosul, which was unthinkable to the top military commanders at the Pentagon. Petraus’ academic studies and military career had prepared him for such a mission. While his fellow field commanders were doing what the military does best — destroying the bad guys and asking questions later — Petraus knew that was counterproductive in terms of winning over the hearts and minds of the Iraqi people. To defeat an insurgency, the U.S. military needed officers who were well-versed in politics, diplomacy, economics, and military strategy.

There was a loose network of officers in the military who sought to fundamentally change the way America conducted its war. They argued that the small wars the U.S. had been reluctant to engage in would be the wars of the 21st century, and that there was a need for a deep and comprehensive counterinsurgency plan in order to win them. The military would be its own worst enemy during this period because of the bureaucratic pushback that change and reform entails. It required a paradigm shift in the role of the military in these conflicts.

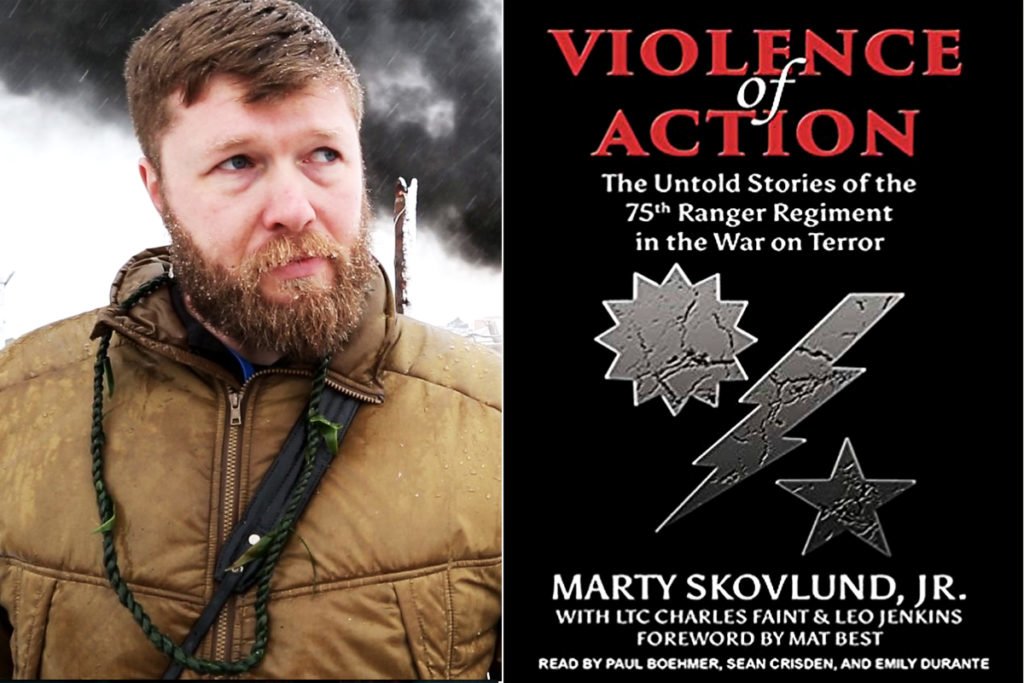

“Violence of Action” by Marty Skovlund Jr., Lt. Col. Charles Faint, and Leo Jenkins

The 75th Ranger Regiment really came into its own during the GWOT. Marty Skovlund Jr., a former batt boy himself, gives an ambitious and in-depth overview of the regiment’s transformation from 2001 to 2011. Skovlund captures details such as the evolution of the combat gear worn to the change in operating procedures and mission scope. “Violence of Action” adds a personal touch with essays written by Ranger veterans and a Gold Star mother.

What stands out is how different every individual Ranger’s experience is in their battalion, yet each seem to have an overwhelming eagerness to complete the mission. Many small stories that would otherwise be lost in time are captured in this collection. Readers will get a sense of Ranger humor and crassness as these elite warriors seek to make the best of otherwise heart-wrenching and painful situations.

Still, a strong sense of duty and pride radiates through the pages as each man recounts their experiences in the toughest infantry unit in the world. No other book on the 75th Ranger Regiment does as much for the average reader in terms of understanding this secretive and oft-misunderstood unit.

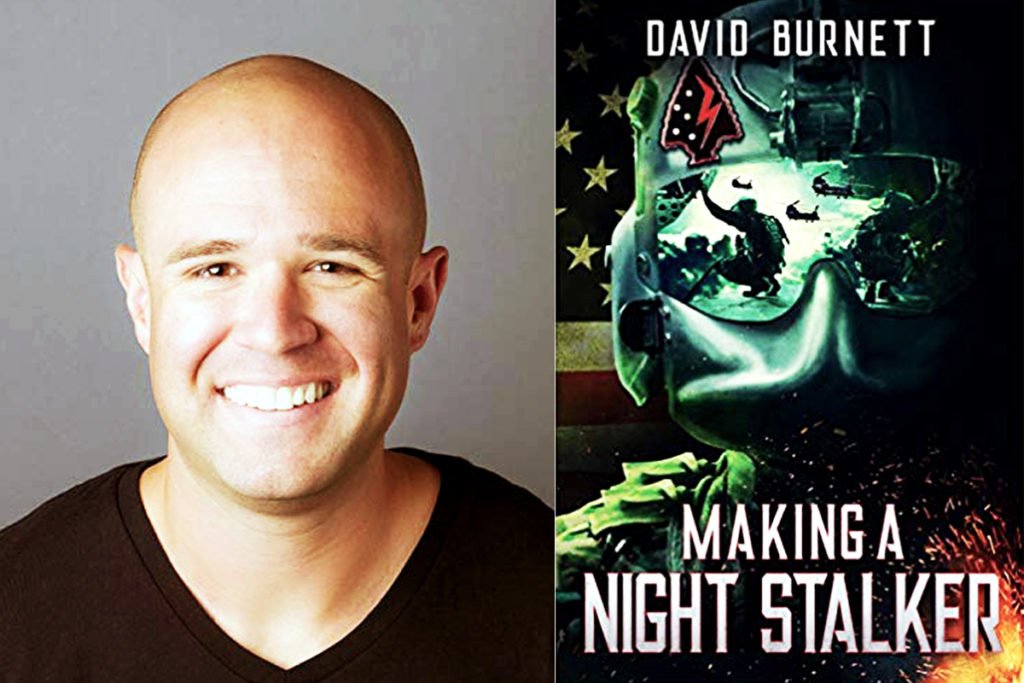

“Making a Night Stalker” by David Burnett

In the special operations world, all the glory goes to the ground pounders — Rangers, SEALS, Special Forces, and the special missions units. Yet the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment (SOAR), known as the Night Stalkers, is to aviation what Rangers are to infantry: an elite unit comprised of the best aviators in the Army.

Specialist David Burnett started his military career as a CH-47 Chinook mechanic, but found the assignment unfulfilling. While he did maintain the helicopters in his unit, he didn’t feel like he was personally doing anything to fight the war. That changed when he saw a group of crew chiefs preparing their helicopters for a mission. Impressed by their professionalism and that they didn’t miss out on the fun of riding on the birds, he applied for selection for the 160th SOAR while deployed in Afghanistan. A good omen appeared to him that day when he saw, for the first time in his life, a Night Stalker’s signature black Chinook on the airfield.

A five-week smoke fest known as Green Platoon is the selection process that each candidate must endure to test their mental fortitude and commitment. Burnette graduated, earned the maroon beret, and was assigned to Alpha Company, which is a Chinook Flight Company.

When he reported to the 160th, his new platoon sergeant handed him a stack of manuals and a list of schools, including Dunker School and SERE (Survival, Evasion, Resistance, Escape) School, that he had to complete before he would be allowed to fly. Getting used to the high operational tempo of his unit, Brunette learned that remaining a Night Stalker during the GWOT was harder than becoming one.

Raul Felix is a 32-year-old Mexican-American from Huntington Beach, California. He currently lives in Long Beach. He served in the United States Army from 2005-2009. Raul writes about sex, dating, women, military life, manhood, Mexican-American culture, motorcycle travel, and anything else he pleases. He currently attends college, bartends, and writes. He has been a featured writer on Thought Catalog. You can find all his written work at RaulFelix.com. He’s on a quest to be one of the greatest writers of our era. You can reach him at [email protected].

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.