Today marks the 77th anniversary of when the U.S. Navy Seabees officially coined their name from the United States Naval Construction Battalions (USNCB; “CB,” pronounced Seabee). The first Seabees were established out of necessity because civilian contractors were used to build bases in the Pacific prior to World War II. Under international law, civilians weren’t allowed to defend themselves in the event an adversary targeted their position.

Rear Admiral Ben Moreell, chief of the Bureau of Yards and Docks (BUDOCKS), fixed this predicament on Dec. 28, 1941, when he requested a specialized unit that could work in remote and austere environments in direct support of Navy and U.S. Marine forces. The early Seabees quickly donned their official motto “Construimus Batuimus,” which translates to “We Build, We Fight.”

This capability gave the Navy a strategic footprint to deploy and provide essential logistics and infrastructure wherever they were needed; the hills of Korea, islands in the Pacific, deserts in the Middle East, polar expeditions in the Arctic — if humans could occupy the area, the Seabees weren’t far behind.

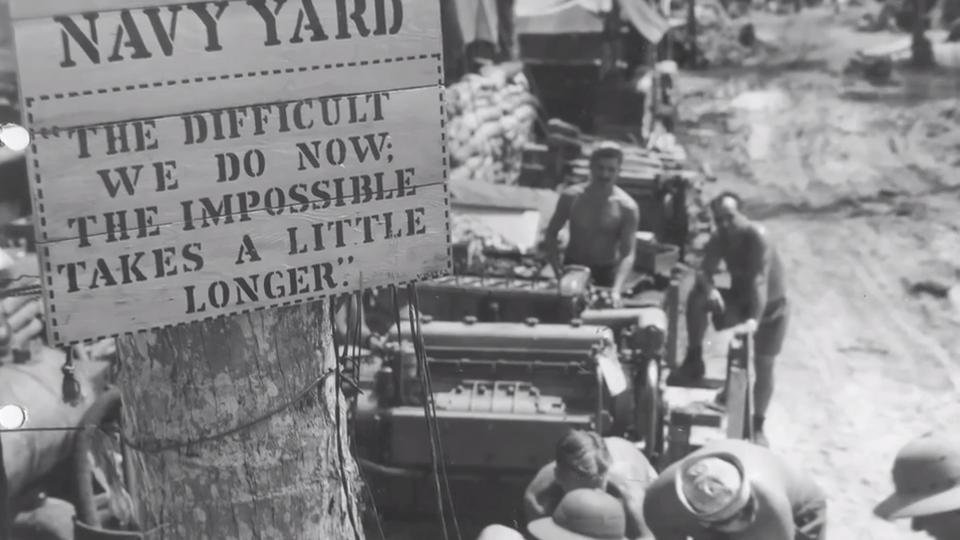

This list pays tribute to the early generations of Seabees who epitomized miraculous battlefield and peacetime achievements others thought could not be done. If given a job, the Seabees have one answer: “The difficult task we accomplish right away, the impossible may take a little longer!”

1. Operations Crossroads

The Bikini Atoll in the Pacific’s Marshall Islands was the test site where the U.S. military released two atomic bombs in the summer of 1946.

The project, dubbed Operation Crossroads, required 42,000 men (37,000 Navy personnel); a combination of sea, air, and land units; and a small contingent of civilian scientists who ultimately made up Joint Task Force 1. The tests were planned to study the effects on ships, equipment, material, animals, and sea life. Before the fleet of men arrived, an advanced party of Seabees from the 53rd Naval Construction Battalion (53rd NCB) arrived in March to conduct the initial survey for the mission. They determined only essential buildings and facilities were required and constructed instrument towers, radio beacons, magazines, photo reference crosses, observation towers, seismic huts, bombing targets, and a recreational space with a max occupancy of 7,000 personnel.

The Seabees were present in every step of the process to ensure all administrative tasks were on course. In August, the 53rd NCB was disbanded and members transferred to Construction Battalion Detachment 1156 to help with cleanup operations.

2. Dong Xoai

The Seabees were among the first Americans to deploy to Vietnam, with their first mission happening as early as 1955. But some of their most heroic exploits wouldn’t come until they started building clandestine Special Forces camps deep in the jungles of Vietnam.

One such camp was at Dong Xoai, about 55 miles northeast of Saigon. Seabee team 1104 was sent to repair the newly established camp in early June 1965, as well as expand it in support of Special Forces ODA 542 and their 200 Montagnard soldiers who were stationed there. On June 9, just days after the Seabees arrived, a force of approximately 2,000 enemy soldiers from the 272nd Viet Cong Regiment mortared the camp and then initiated a full-scale assault to capture it.

The battle raged for four days, and the Seabees fought side-by-side with the Special Forces soldiers to defend the camp. One Seabee, Marvin Shields, was wounded by mortar fire early in the battle but continued carrying ammunition up to the firing lines. He was again wounded, this time being shot in the jaw, but fought on and even helped evacuate the mortally wounded Special Forces commander to a safer position within the camp. He then returned to the line and volunteered to maneuver outside of the camp toward an enemy machine gun position alongside the new acting commander of the Special Forces A-team.

They made it into position, and Shields loaded a 3.5-inch rocket into the commander’s rocket launcher, who then fired and successfully took out the machine gun and its crew. On their return to the camp, Shields was wounded a third time — this time shot through both legs. The commander ordered him and five other wounded Seabees to be evacuated, but Shields’ wounds proved to be fatal, and he died during the evacuation.

The battle took the life of two Seabees, Shields and William C. Hoover, along with seven more who were wounded. Shields was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for his heroic actions in combat while wounded and under intense enemy fire; he also received the Purple Heart with two gold stars. To this day, Seabees have continued their relationship with the special operations community and routinely deploy alongside special operations forces all over the world

3. Ghost Battalion

During the Vietnam War, the North Vietnamese continually attacked an airstrip at Dong Ha, the capital of Quang Tri Province, causing enough damage and mayhem that the Seabees were called in to complete a top-secret temporary duty assignment. Their mission was of the highest priority and utmost importance to counter the offensive and gain a tactical advantage. Their instructions were simple: go to site “X” and construct a 3,500-foot-long airfield capable of handling C-130 airplanes, living quarters for more than 500 men, and a 90,000-square-yard helicopter pad. They had fewer than 45 days to complete the project.

Seabees from the 32nd Naval Construction Regiment and Naval Mobile Construction Battalions (NMCB) first arrived on Sept. 15, 1967, at site “X” in Quang Tri located north of Ho Chi Minh City. Because of the secrecy and nature of their work, the Seabees called themselves the “Ghost Battalion” and flew the skull-and-bone Jolly Roger flag. In just two days — under heavy rain, unbearable weather conditions, and limited food rations — the Seabees completed 90 percent of the helicopter pad. No problem was met with dismay, including half of the airfield containing 11,000 graves. With only a week to complete, the Seabees called in local Vietnamese civilian laborers to assist in removing the burial areas.

The site remained a secret until North Vietnamese and Viet Cong snipers witnessed flying crane helicopters bring in heavy-duty equipment. Although Dong Ha was just 10 miles from their location, convoys carrying materials, rough terrain forklifts, and bulldozers were transported from Phu Bai located 55 miles away because of the threat of nighttime sabotage raids on critical supply bridges. The Seabees braved sporadic and direct rifle fire and mortar attacks and completed site “X” in 38 days. It later became a key installation in the Vietnam War.

4. Cubi Point Naval Air Station

The Seabees’ “Can-Do” attitude while constructing the Cubi Point Naval Air Station in the Subic Bay, Philippines, allowed them to move mountains to complete their mission. No, really — they cut a mountain in half to prepare a 2-mile-long runway, and that was only part of the arduous earth-moving project that took five years and 20 million man-hours to complete. Beginning in 1951, the U.S. Navy declared Cubi Point, part of the Bataan Peninsula, as the best operational position to launch airborne and carrier missions in future conflicts. This determination was due to its geological position and protection from mother nature’s hellacious typhoons. The problems that most civilian contractors thought to be insurmountable were clearing the thick jungle vegetation and the daunting Zambales Mountains.

The benefit over prior Seabee missions is that they didn’t have to worry about gunfire because this was a peacetime mission, yet they still had run-ins with trouble. On numerous occasions, bands of monkeys, wild pigs, pythons, and carabaos became unbearable nuisances. The natives also told them to beware of roaming Philippines Communists, called Huks, who frequently pillaged nearby villages. The unknown threat of attack may have been present, but it was never realized.

By 1956, the Seabees blasted coral into a critical section to the fill the Subic Bay, cut down trees as tall as 150 feet, relocated a native fishing village, and flattened 1,200 feet of a mountain — the total amount of work is said to equal building the Panama Canal. The labor created a spectacular air station and an aircraft carrier pier that has since played an integral role in Operation Desert Storm/Desert Shield.

To this day, the project is considered one of the greatest peacetime accomplishments ever conducted by the U.S. Navy.

5. Assault of the Doodlebugs on Tinian, July 1944

The Seabees were involved in every major invasion during World War II, supporting and fighting alongside their infantry brothers at Guadalcanal, Los Negros, Tarawa, Munda, Saipan, Tinian, Attu, Iwo Jima, Guam, Samara, Okinawa, Salerno, Sicily, and Normandy. The tiny island of Tinian, which sits 3 miles southwest of Saipan, soon became the next target of U.S. Marines, who only months before earned their scars against fierce Japanese resistance. Tinian served as a critical location in the Pacific, and both the Japanese and the Americans were going to do everything to control it.

However, there was a challenge that battlefield commanders faced: how the assault force would overcome the bottleneck of two small strips of beach on the northwest shore guarded by fortified Japanese positions and surrounded by 8- to 15-foot jagged coral reefs. The situation was dicey at best, so the Marines turned to the Seabees and consulted with Captain Paul J. Halloran and Lieutenant W.G. McRae. The pair conceptualized the Doodlebug, an LVT (landing vehicle, tracked), to get past the coral reefs. They jerry-rigged the AMTRAK with large pieces of steel taken from Japanese sugar mills in Saipan and made a makeshift ladder that rested on the top.

On July 24, 2nd Marine Division feigned an assault on the southern part of Tinian Town by faking a landing in concert with several supporting battleships that hammered their battery defenses with artillery. Meanwhile, 4th Marine Division launched a full-on assault in the northwest, several Seabees fighting alongside to reach a reconnaissance point in preparation for the Doodlebugs launching from Saipan 3 miles away.

Ten Doodlebugs arrived to the edge of the reef, attached hooks that secured tightly on the highest points of the cliffs, and reversed, leaving a ramp that stood as a bridge over the pointy obstacles. Ramp crews docked nearby and dropped their latches, releasing the full vehicular package of military firepower on the island.

In just over a week’s time, Tinian Island was largely secured despite a few skirmishes here and there. The ingenuity of the Seabees earned the praise of Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, who later described the invasion as “probably the most brilliantly conceived and executed amphibious operation in all of World War II.” Two months later, the Seabees transformed the island into the largest strategic air base in the world.

6. Operation “Crippled Chick”

Anti-aircraft guns belonging to communist North Korea and China shot down an increasing number of American aviators in the spring of 1952. The USS LST 799, a refashioned helicopter landing ship, saved 24 pilots from the Sea of Japan. American ground forces were on the retreat, losing precious territory for the past two years — their only viable answer was from the air. As a result, Allied pilots conducted bombing runs daily on critical supply routes of North Korean positions but had no safe bail-out options if their plane became disabled.

The only two options at their disposal resulted in suffering, agony, or death: skip the plane into the enemy-controlled Bay of Wonsan and, if one survived, wait in frigid hypothermic waters until Navy destroyers came to their rescue — or crash into North Korea-controlled territory and risk being captured. The cost of losing any teammate weighed heavily on all, and on June 6, 1952, Operation “Crippled Chick” tasked Seabees with creating an emergency landing strip on the small island of Yo-Do, near the port city of Wonsan on the enemy-controlled harbor.

Given a 45-day timeline, the Seabees worked tirelessly for 16 hours a day, often under fire by North Korean bombardments. Sixteen days later, the Seabees constructed a 2,400-foot runway and sent out the discreet call over the transmitter: “Steak for dinner.”

The coded message signaled all frantic Allied pilots in the area that the airbase was ready. Once the pilots landed safely, the Seabees would refit and refuel the planes if they were salvageable and send them on their way back to aircraft carriers and more risk-averse bases.

Editor’s note: A previous version of this article said the Seabees operated in the “jungles” of Korea. There are no significant jungles on the Korean Peninsula, so the article has been amended to say “hills” of Korea — a more accurate representation of their geography.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.