The Destruction of a Warship: A Disgruntled Sailor or a ‘Sloppy Investigation’?

The USS Bonhomme Richard burns in San Diego in July 2020. A member of the crew was formally charged in December 2021 with starting the fire on the warship. US Navy photo.

Navy prosecutors presented no direct physical evidence this week linking a junior sailor to a fire they said he started aboard the USS Bonhomme Richard that destroyed the billion-dollar warship. The defense described the government’s case as speculation reliant upon a “sloppy investigation.”

The pre-trial Article 32 hearing for Seaman Apprentice Ryan Sawyer Mays lasted three days on Naval Base San Diego. The prosecution relied heavily on the testimony of one witness, Petty Officer 3rd Class Kenji Velasco, who testified he’d seen Mays at the scene of the fire right before it began.

However, the defense highlighted several times that a joint investigation conducted by the Naval Criminal Investigative Service and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives turned up no direct evidence against Mays. The defense also presented expert opinions that an electrical fire could be to blame.

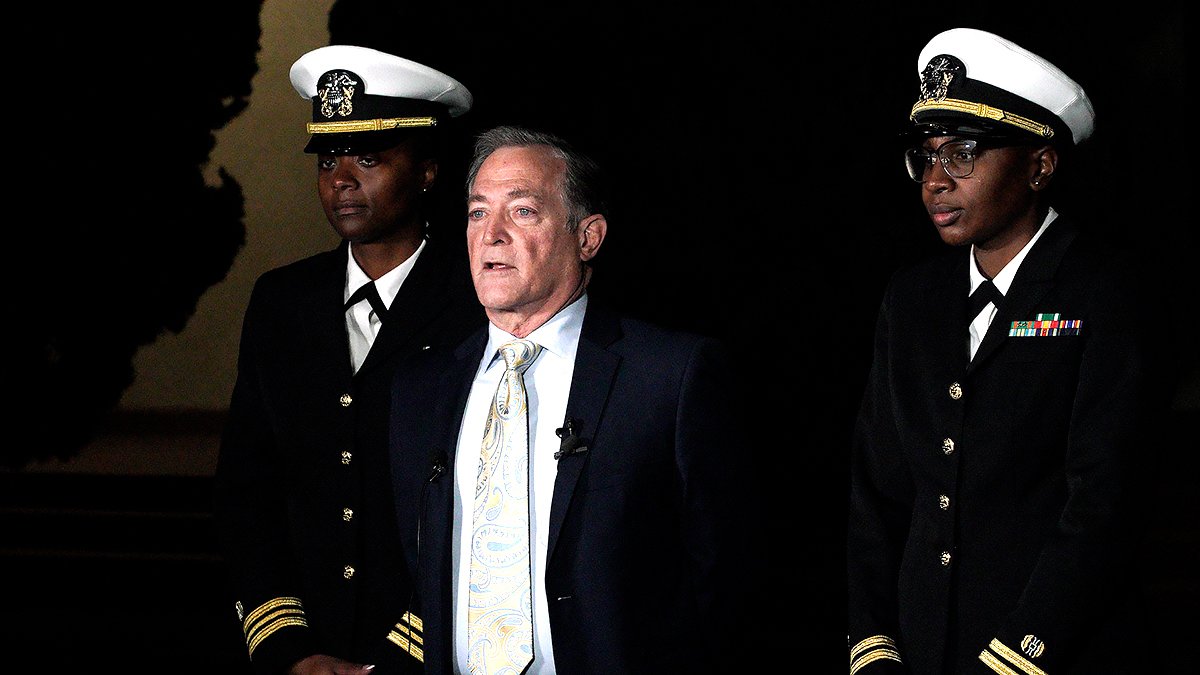

Hearing officer Navy Capt. Angela Tang will offer an opinion in the coming weeks on whether there is enough evidence to move the case to a general court-martial, though the convening authority, Vice Adm. Stephen Koehler, commander of 3rd Fleet, has the final say on whether to proceed with a court-martial.

Here is what you need to know about the case of the United States v. Ryan Sawyer Mays.

An Intentional Fire?

During testimony Monday, Dec. 13, ATF Special Agent Matthew Beals, a certified fire investigator, said he believed the fire on the warship was caused by arson. Beals said he’d found evidence that an individual had set fire to a stack of extra-large cardboard boxes using either diesel fuel or mineral spirits, both of which were easily accessible to sailors aboard the ship.

Beals and other investigators determined the fire had originated in the ship’s lower vehicle storage area, known as “the lower V,” where vehicles are stowed while the vessel is underway.

However, since the ship was in the middle of a two-year overhaul, the lower V served as a storage area for all manner of shipboard and construction-related items, including large boxes, ammo carts, pallets, spools of line, hoses, and more.

Naval prosecutors called Velasco on Tuesday. As the government’s key witness, Velasco said he’d been standing watch on the upper vehicle storage area, one deck above the lower V, the morning of the fire. He swore he was “100%” certain that he’d seen Mays enter the lower V shortly before the fire broke out sometime around 8 a.m. on July 12, 2020.

Prosecutors believe Mays started the fire and then used one of two ladder wells to escape the lower V unseen by Velasco or other sailors.

Flames quickly engulfed the deck and spread through the ship, forcing the crew to flee.

The fire aboard the Bonhomme Richard burned for more than four days, injuring 68 and resulting in the warship being decommissioned and scrapped by the Navy. A report on the fire released in October concluded the fire was a result of arson but that the ship was lost because of a series of leadership, safety, and planning failures that resulted in an “inability to extinguish the fire.”

Another Theory

The defense presented two witnesses who suggested arson wasn’t the only available explanation for the fire: Andrew Thoresen, an electrical engineering consultant with 20 years of forensic experience investigating 3,000 fires, and Phil Fouts, a former ATF fire investigator and instructor.

Both testified that the Naval Criminal Investigative Service and ATF investigation had improperly ruled out the possibility of an accidental electrical fire caused by one of two forklifts stowed in the lower V. During his investigation, Thoresen said he’d found a damaged wire on the forklift that showed signs of arcing, something he said the government’s investigators had failed to look into. One portion of the wire, he explained, may have made contact with a metal part of the engine compartment, melting part of the copper wire.

Thoresen also pointed out that investigators had found lithium-ion batteries at the scene, which were only visually inspected by investigators. The batteries should have been X-rayed to check for internal damage, Thoresen said.

Lithium batteries are a common cause of fires he investigates, Thoresen said. “I do about 300-some fires a year. This is in the top three or five causes,” Thoresen said. “They’re a major [cause of fire] we see all the time.”

Without a lab inspection, he said, there was no way to eliminate the batteries as a potential cause for the fire.

Fouts, siding with Thoresen, said the cause of the fire should have been classified as unknown because an electrical incident couldn’t be ruled out. When pressed by the prosecution, Fouts said the investigators had used the wrong approach to determine the cause of the fire. Rather than rule out possibilities and declare the cause as unknown, Fouts said, investigators had applied negative corpus, a theory in which an absence of a clear cause of a fire is taken to be evidence of arson.

“They made some speculations of the heat source or fuels ignited,” he said. “I think there’s been some leaps made there to find this conclusion.”

A Lack of Evidence

In the end, the defense hammered on the government’s lack of physical evidence tying Mays to the blaze. A lawyer for Mays noted that, despite interviewing more than 375 individuals, logging thousands of pages of documents, and combing areas near the fire’s origin and around the ship, the prosecution had found no physical evidence linking the accused sailor to the fire.

No DNA or fingerprints matched Mays at the scene. In fact, the only DNA found in one of the ladder wells was identified as female, Beals said.

The defense also noted that, while Velasco said that the sailor he’d seen enter the lower V wore blue coveralls, multiple witnesses testified that Mays had been wearing a green navy working uniform, or NWU, the morning of the fire.

Prosecutors argued Mays had donned blue coveralls to start the fire, fled the lower V using one of the ladders, and then changed back into his NWUs to throw off any witnesses. But Gary Barthel, one of May’s attorneys, said that narrative was strictly speculation.

During closing comments Wednesday, Navy prosecutor Cmdr. Richard Federico implied there might be more evidence against Mays, though he did not specify what kind. Instead, he argued that the purpose of the Article 32 hearing wasn’t to prove Mays was guilty but to show there was probable cause to convene a court-martial.

“What we have submitted to you throughout this hearing for probable cause is not a close call,” Federico said. “We need not present all of our evidence at this time.”

A Question of Character

With little physical evidence, the prosecution spent considerable effort on Mays’ attitude. Prosecutors portrayed Mays as a sailor without discipline and prone to lying. Multiple witnesses testified that the junior sailor was unpopular among his peers, which they attributed to his “cockiness” and “arrogance.” They said Mays had a chip on his shoulder, having dropped out of the Navy’s Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL training and being assigned to deck duties aboard the Bonhomme Richard.

During the hearing, prosecutors showed several video clips of NCIS agents interrogating Mays. In one interrogation captured on video, now-retired NCIS Special Agent Al Porter, himself a former SEAL, built a rapport with Mays before diving into questioning.

Mays told Porter, “The fleet Navy is fucking gay,” and that he planned to return to BUD/S as soon as possible. He told Porter that he had stayed in BUD/S until Hell Week, which comes at the end of the course’s first phase, before being medically dropped for an injury. However, Porter was told Mays had quit the course just five days in, long before Hell Week.

Porter’s trust in Mays shrank further when he caught the sailor in an alleged lie about his relationship with a female sailor. Mays told both Porter and Beals that he had been previously engaged to a female sailor who was assigned to another ship, but they had gone their separate ways when she became pregnant by another man. However, Porter said the female sailor told him she had been the one to break off the relationship with Mays because she believed he’d attempted to impregnate her without her consent.

The female sailor did not testify in the hearing.

In his closing comments, Federico pointed out that Mays had spent the last three days in court in the wrong uniform, wearing the rank of seaman rather than seaman apprentice. Mays had been demoted, Federico said, after testing positive for a controlled substance earlier in the year.

“He is not a truth-teller,” Federico said. “He lied about his time in BUD/S, he wasn’t truthful about his relationship with the other sailor […] he even spent the week in the wrong uniform.”

The only time the prosecution argued that Mays was telling the truth was when he allegedly made a statement to a brig guard that prosecutors argued amounted to a confession. Master-at-Arms 1st Class Carissa Tubman testified that, as she’d escorted Mays to the brig, she’d heard him say, “Well, I’m guilty, I guess. I did it.”

The defense argued Mays was being sarcastic, but the prosecution said it was an admission. Tubman also said during her testimony that Mays had ended his comment with “It had to be done,” but the defense said she’d never mentioned that line in her initial interview with investigators.

‘A Sloppy Investigation’

Mays’ defense did not push back against the picture of Mays as cocky, arrogant, and at times unpleasant. But lying about his time at BUD/S and being a disgruntled sailor, his team argued, didn’t mean he tried to hazard a billion-dollar vessel.

Barthel and the defense picked apart the prosecution’s arguments over three days, citing failures and inaccuracies by investigators and inconsistent testimonies made by some of the witnesses. They said Mays, like many BUD/S dropouts, seemed salty and arrogant, which seldom leads to long-lasting friendships with other sailors and instead makes him an easy target. Several supposed lies the prosecution presented, Barthel argued, were just as likely to be misunderstandings or faulty memory.

“Sometimes people say things that might not be accurate,” Barthel said. “It doesn’t mean they’re lying.”

In his closing comments, Barthel called the prosecutors’ material a “sloppy investigation” more concerned with finding somebody to blame than the actual cause of the fire. Barthel said investigators had developed a narrative early on that Mays had set the fire while the sailor had maintained his innocence since the day of the fire.

“They tried to pin him down. For nine hours, they interrogated him. He constantly denied going to the lower V, he constantly denied starting the fire,” Barthel said. “He was labeled a liar. They constantly tried to get him to play into a narrative. He refused.”

Read Next:

Dustin Jones is a former senior staff writer for Coffee or Die Magazine covering military and intelligence news. Jones served four years in the Marine Corps with tours to Iraq and Afghanistan. He studied journalism at the University of Colorado and Columbia University. He has worked as a reporter in Southwest Montana and at NPR. A New Hampshire native, Dustin currently resides in Southern California.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.