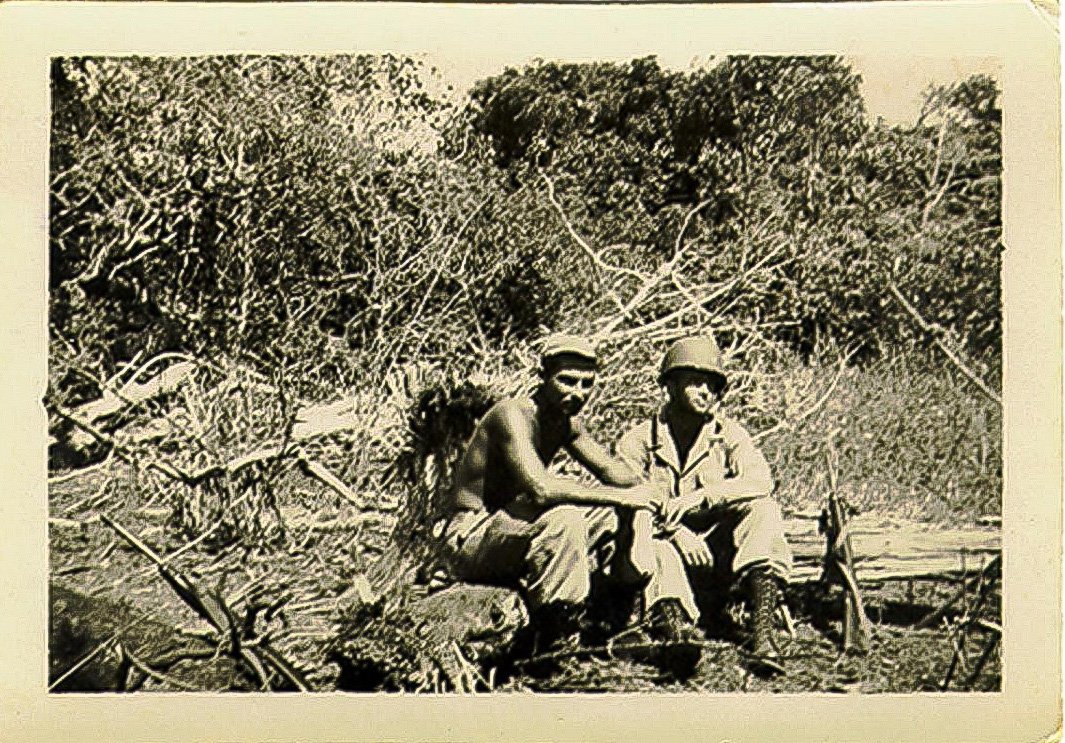

Neil Gray, far left, served with the Office of Strategic Services in the China-Burma-India theater and was one of the early pioneers of the US Air Force’s Special Reconnaissance career field. Photo courtesy of the Grey Beret Association.

Airborne operations in World War II called for specialists capable of determining the weather in austere and dangerous environments. In 1942, Cornelius “Neil” Gray joined the US Army Air Forces. He was selected for an unconventional program that created meteorology-trained weather observers, also known as “guerrilla weathermen.”

During World War II, Gray served at a weather station in the China-India-Burma theater before answering a request put out by the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the predecessor of the CIA. It was “looking for people to assume various missions behind the Japanese lines,” Gray told the New York State Military Museum in 2002. “Being a weather observer at that time, they thought they’d like to establish weather stations in the rear of the Japanese.”

Weather forecasters served varied roles between the US Army Air Forces and the OSS. Their missions involved being put ashore by US submarines and supporting Allied airstrikes in preparation for Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s invasion forces.

Guerrilla weathermen like Gray underwent specialized training with the OSS. He participated in rudimentary communications courses and learned how to send and receive 20 words per minute using Morse code. Transmitting coded observations — such as the temperatures on the ground and barometric pressure — to airlift pilots to determine flight paths proved pivotal in Gray’s operations overseas. In addition to other secure communications, Gray received instruction on how to handle various types of weaponry and demolitions. But perhaps the most critical training of all involved how to survive, evade, resist, and escape from enemy pursuers through the thick jungle vegetation.

In June 1945, Gray parachuted behind enemy lines into Central Burma as a member of Detachment 404 — an OSS operational group tasked with collecting intelligence (including on weather) and building a resistance force. Another “guerrilla weatherman” and two Burmese riflemen joined him in Burma, where the small group helped train hundreds of Burmese guerrillas and launched raids targeting Japanese officers.

“We went into just going in as a weather observer to various and much broader missions,” Gray said. “Looking for possibly preparing an airfield for an American group to come in and release prisoners of war. We never got to the point where we actually reconnaissanced the prisoner of war camps, but that was part of our mission.”

Despite horrible living conditions, Gray survived 77 days in the jungle. Resupply airdrops only occurred every three or four weeks, so the guerrilla weathermen recruited local tribe members to provide them with rice. Gray went to great lengths to augment the team’s rice diets with protein-rich meat. After Gray obtained a suppressed .22 weapon, the team lived off monkey meat for nearly a month.

The OSS was so successful in their ambushes that the Japanese sent a massive response force to hunt them down.

“We had been a little bit of a thorn in their sides,” Gray said. “They reacted to this by sending 45 dogs and 1,900 line troops down to see if they couldn’t eradicate us.”

Gray credits his survival to the abrupt end of the war via the dropping of the atomic bombs. Following Japan’s surrender, Gray and his team coordinated with a British speedboat that extracted them from the Burmese jungle.

“I probably owe my life to the atom bomb being dropped,” Gray reflected.

In the aftermath of World War II, Gray left the military to attend Siena College, then Georgetown University. While he was attending Georgetown’s School of Foreign Service, the Korean War broke out, and Gray was activated from the Reserves to the US Army as a second lieutenant. Gray served as a counterintelligence agent, and he was responsible for interviewing prisoners of war. He then went to language school to learn Mandarin before participating in classified intelligence assignments in Asia and Europe.

Gray served in his third war and deployed to Vietnam when the conflict began, taking command of an element of the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment. In 1968, after 27 years of dedicated service, Gray retired as a major. He later worked for the Atomic Energy Commission and General Dynamics, including on a special project in the Navy’s Nuclear Propulsion Program. In 1998, he was inducted into the Air Commando Hall of Fame and is considered one of the pioneers of the Special Operations Weather Team occupational field.

Gray died in 2012.

In 2019, the SOWT career field became Special Reconnaissance — one of four special warfare jobs in the Air Force — according to the Grey Beret Association, an organization that exists to preserve the historic legacy of combat weathermen past and present, including pioneers like Gray from World War II.

Read Next: To Hell and Back: The Epic Adventures of British Commando Freddy Spencer Chapman

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.