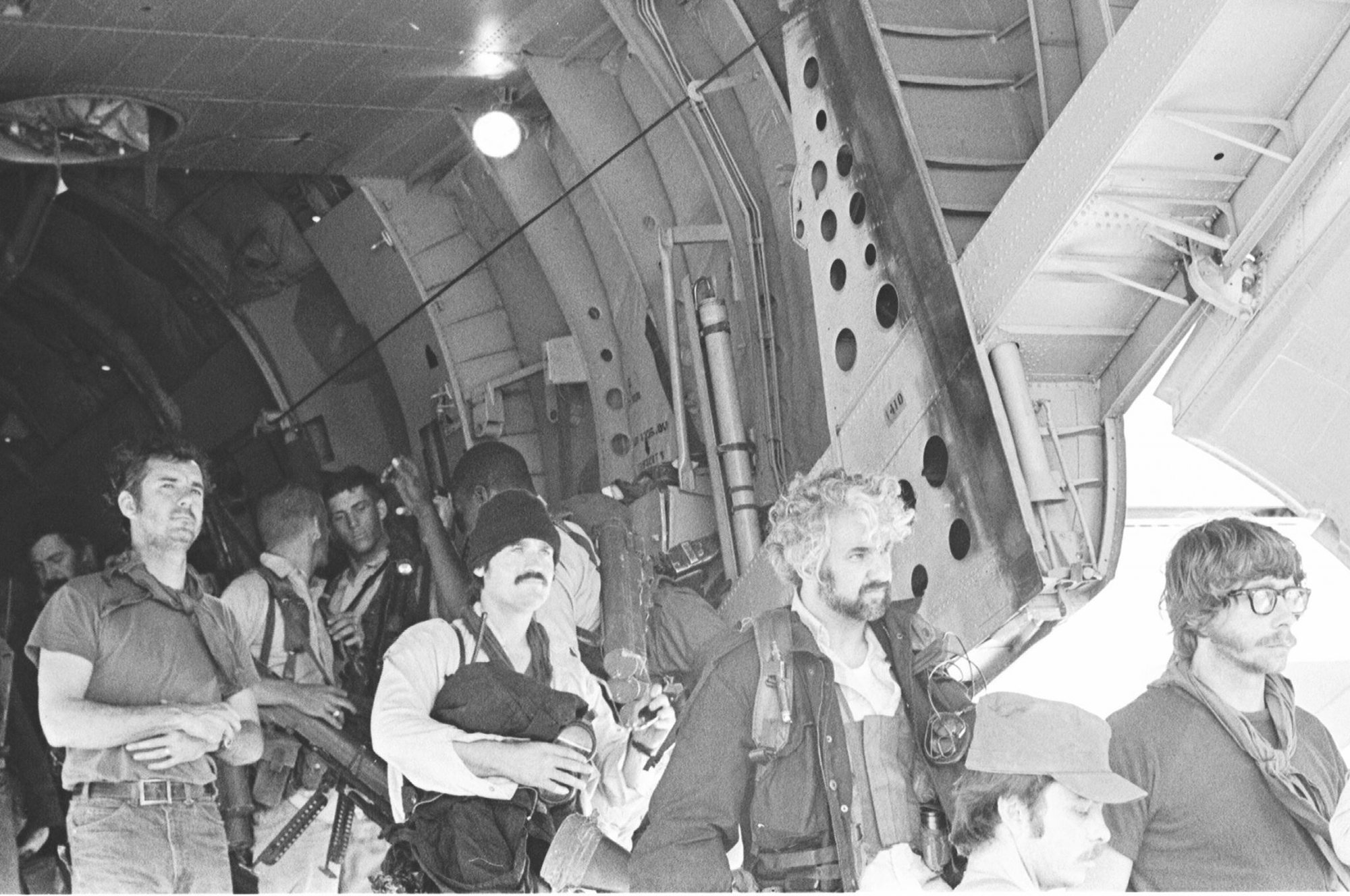

Disembarking a C-141 aircraft, left to right, Dennis E. Wolfe, Durwin D. Dengerud, Lawrence N. Freedman, William L. Welsch, and Mike R. Vining. Photo courtesy of Mike Vining.

On Sunday morning, Nov. 4, 1979, 3,000 university students, many armed, stormed the US Embassy in Tehran. Two weeks prior, President Jimmy Carter had allowed former Iranian head of state Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi to enter the US for cancer treatment. The radical protesters took more than 90 hostages, including 63 Americans, planning a nonviolent three-day revolt using the hostages as leverage to demand the Shah’s return for trial. But what unfolded was a 444-day saga that became known as the Iranian hostage crisis. Only two days after the US Embassy was seized, the US military was tasked with the rescue efforts code-named Operation Eagle Claw.

Staff Sgt. Mike Vining, 29, was participating in winter warfare training in Breckenridge, Colorado, when his squadron was alerted to immediately return to Fort Bragg, North Carolina. Vining had been a plank owner or founding member of the Army’s then-brand-new counterterrorism team established by Army Special Forces legend Col. Charles Beckwith, based on the British SAS. The unit collected the best the Army had to offer, and Beckwith valued those with combat experience or unique skill sets. Vining had both, previously serving as an explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) specialist in Vietnam for a 12-month tour, where his composite team was responsible for the destruction of the largest enemy weapons cache in the war.

Operation Rice Bowl

When Vining and other members of B Squadron returned to their unit’s compound, they were briefed on the situation and put into isolation to begin planning. The planning stages were dubbed Operation Rice Bowl. The name was picked to suggest, in the event their mission brought scrutiny, that something was going on in Southeast Asia away from the Middle East.

“We were really fearful of any satellites picking up any indication of what we were trying to do,” Vining told Coffee or Die Magazine in a recent interview. “The Russian satellites and so forth. We were worried that the Russians would alert the Iranians.”

The assault teams moved to Camp Peary in Virginia, home to “The Farm,” where CIA operations officers are trained to perform covert missions. The site was transformed to create a mock replica of the US Embassy in Tehran. The CIA even built a 3D model similar to the one used in preparation for the Son Tay Raid in Vietnam, where one could take the roof off and see the interior within.

“When you do military operations and stuff like that you create what’s called a sand table,” Vining said. “The Rangers do that in Ranger School. You draw in the sand what the objective looks like, points that you need to know about. And so it’s just like a sand table, but very elaborate, very sophisticated. It was a great model.”

In Iran, the 27-acre US Embassy compound housed 50 hostages guarded by some 500 Iranian Revolutionary Guards, while three additional hostages were kept in the Iranian Ministry of Foreign Affairs building 16 blocks away. Throughout the crisis, several hostages were released early, and a secret operation dubbed Canadian Caper helped others escape to a safe house and use Canadian passports to leave the country. This operation was later chronicled in the Hollywood movie Argo.

The planned assault on the embassy was the easy part. It was getting there that was the challenge and that would spiral out of control for the ill-equipped joint-military operation.

The Elaborate Plan

Beckwith initially proposed a parachute infiltration, but that was quickly scrapped once predictions estimated the ground rescue force would likely suffer a 7% casualty rate right at the start. Instead, planners came up with a helicopter raid, and the training resumed at Yuma Proving Grounds in Arizona.

The Navy’s helicopter pilots lacked tactical expertise. They were not used to flying at nap-of-the-Earth altitude under night vision goggles, nor were they equipped to transition from desert flying to urban flying. The Marine Corps pilots had no prior experience working with the Navy pilots. Moreover, both the Navy and Marine models of the Sikorsky H-53 helicopters were old and worn out, with frequent mechanical problems. In the end, Marine aircrews were selected to fly Navy helicopters, the first of several decisions to pair up mismatched equipment and personnel that would haunt the mission.

Weeks before the pilots or assaulters were set to launch on the operation, Beckwith enlisted Maj. John Carney, an Air Force Combat Controller (CCT), to install a hidden airstrip with lights that were only visible under night vision goggles. The site was called Desert One, about 200 miles from Tehran, and would be the operation’s initial rally point and refueling site. Next came a small advanced force that would infiltrate Tehran and secure a warehouse containing five Ford trucks and two Mazda vans. The vehicles had facade compartments that would conceal the assaulters as they went through Iranian checkpoints to reach the embassy.

“We had with us people that spoke Farsi really well,” Vining said, adding some of the members included former Iranian generals. “They were going to be our drivers on the vehicles.”

The plan was elaborate. Eight US Navy RH-53D Sea Stallion helicopters would fly from the USS Nimitz in the Arabian sea to Desert One. There they would meet the assault force, which would reach Desert One on Air Force C-130s. The helicopters would refuel, and the assaulters would then board the helicopters to fly to a site 50 miles outside of Tehran, called Desert Two. During daylight hours, Vining and the assaulters would stay in a warehouse, while the helicopters hid at Desert Two. The raid would come on the second night.

The escape was even more audacious: The assault teams would move the hostages to a nearby soccer stadium, where helicopters would fly in to pick them up. Meanwhile, a Ranger element would secure a nearby air base. The helicopters would ferry the raiders and the hostages to the air base, where Air Force C-141s would arrive to fly the whole force home.

If anything went wrong, the teams had contingencies to escape.

“We had maps and everybody was carrying money,” he said. “I had $10,000. I had $5,000 in American money and I had $5,000 in Iranian money to help drive our way out. We had stuff to jump-start vehicles if we had to steal a vehicle and get out of Tehran. Then our E&E (Escape and Evasion) plan, we’d head up into the mountains and work our way across the mountains towards Turkey, hopefully running into some Iranians that were friendly, and would help us.”

The plan, however, never made it past Desert One.

Operation Eagle Claw

On April 20, 1980, the complex plan was set into motion. The rescue ground force was flown to Germany, then to Egypt, before the flight to Desert One.

“But as soon as we landed, we see headlights come in, and there was a bus coming down the road,” Vining said. “So Beckwith hollered, ‘Stop that bus!’ So one of the Rangers fired a 40 mm round at the front of the bus. And the bus came to a stop and we boarded the bus.”

Two more vehicles came down the road, a fuel truck and a pickup, who the raiders believed were likely gas smugglers. A Ranger fired a rocket at the fuel truck and it caught fire. “That tanker blew up because it had been sitting there on fire and lit up the sky with a giant fireball,” he said. “It was like, we are really announcing here we are.”

That was only the beginning.

The helicopters were late. Among the eight Sea Stallion helicopters scheduled to land at Desert One, only six arrived, one of which was immediately declared out of service for mechanical issues. Five was the bare minimum the plan allowed to continue the rescue mission.

Vining and his assault team sat inside the EC-130 that had brought them to Desert One. They would board the Sea Stallions after the helicopters took on the fuel that the EC-130 had brought for them. In the center of the EC-130, the large communications pod normally on board the aircraft had been swapped with a bladder of 5,000 gallons of fuel.

On the improvised airstrip, the Air Force CCTs told two of the waiting helicopters to move away from the sandblast of the EC-130’s propellers. One of the helicopters couldn’t taxi on the ground because it had suffered a hard landing and flattened its tires.

“He had to actually lift up off the ground to reposition,” said Vining. “He lifted up, kicked up some sand, [the pilot] got vertigo, and he turned and he twisted. Next thing I know you feel this movement of our aircraft and then the rotors of the helicopter actually cutting into the top of the fuselage.”

The left front cockpit door blew in and behind it was nothing but fire and flames. As the Sea Stallion crashed into the EC-130, its fuel tanks exploded. “The people that witnessed this from the outside said our two aircraft completely disappeared,” he said, “disappeared into a fireball. They thought that both aircraft were at that instant gone.”

Eight Americans died in the initial fireball. Inside the doomed plane, next to a gas tank, Vining thought for sure he was going to as well.

“I really didn’t believe I could make it from my position to that door,” Vining recalled. “I thought I was going to die that day. I was surprised when I actually made it to the door and jumped out. I came out and did a somersault, landed on some hot metal, came to my feet, and just ran.”

As Vining sprinted to safety, he started to hear grenades and small-arms ammunition cook off in the fireball. Then came six Redeye missiles shooting out into the air and into the desert. In the chaos, all of the other helicopter aircrews left their helicopters and ran to fixed-wing planes.

There would be no rescue mission. The task force piled onto the remaining helicopters and planes and returned to a US base in Oman.

“Contrary to what you ever heard, there was no head count taken at Desert One,” he said. “We didn’t know who we had or who we didn’t have until we got to Oman. Then we figured out that we lost eight people, three Marines and five Air Force crewmen that were in the front of the cockpit.”

Operation Eagle Claw was later cast as the “Desert One Debacle.” The Iranians split up the hostages so that they were no longer all in one spot. Still, a second hostage rescue mission was planned, but it never came to fruition. In June 1980, the Iranians released an American hostage with multiple sclerosis. The rest of the hostages were released in January 1981.

Although Eagle Claw wasn’t a success, its failure kick-started the buildup of US special operations forces and capabilities. The 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment, the Joint Special Operations Command, and the rest of the US special operations forces can all trace their beginnings to Desert One.

Read Next:

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.