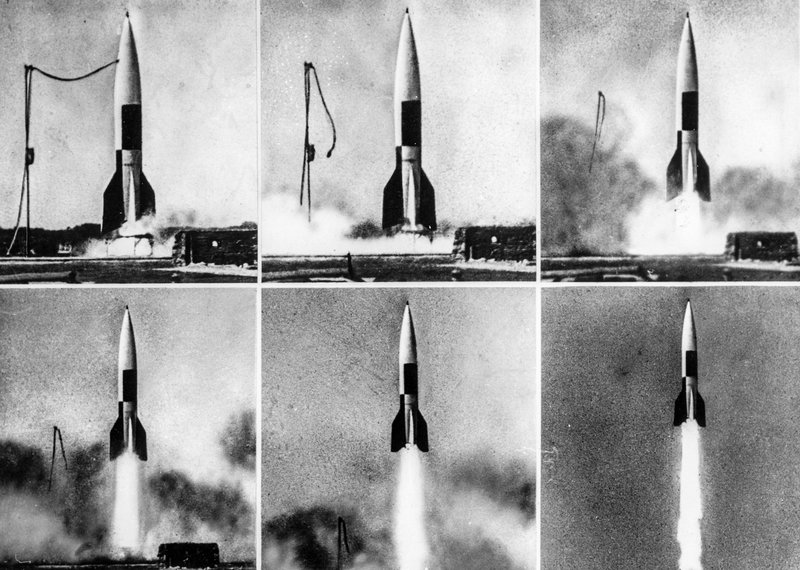

In 1949, the "Bumper-WAC" became the first human-made object to enter space as it climbed to an altitude of 393 kilometers (244 miles). The rocket consisted of a JPL WAC Corporal missile sitting atop a German-made V-2 rocket. The V-2 was developed by Wernher von Braun's team of German researchers, who surrendered to the United States at the end of World War II. Photo courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech.

When the existence of Operation Paperclip was first revealed to the American public in 1946, the general consensus in the country was that it was a bad idea. Prominent figures, including former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, were vociferous in their disapproval. The United States had, after all, just fought a world war against the Nazis. They were the bad guys.

For the architects of Operation Paperclip, it wasn’t so cut-and-dried. In the larger terms of US national defense, the criteria for who could be classified as “the enemy” was quickly changing. Even before the fall of Berlin, American intelligence agents had begun quietly tracking down and recruiting Nazi scientists and engineers with expertise in electronics, medicine, aerospace, rocketry, chemistry, and other wartime technologies — expertise that could give the Western powers a greater edge in the burgeoning Cold War. In all, more than 1,600 Nazis were given safe haven in the United States so their skills and knowledge could be exploited to maintain American military superiority.

After The New York Times and Newsweek broke the news about Paperclip in 1946, government officials assured the American public that the individuals recruited in the operation were the “good Nazis,” insisting that none of them had been complicit in the atrocities committed by Hitler’s regime. In reality, however, there were a number of known war criminals among them, including some who had conducted human experiments, used slave labor, and even overseen the systematic murder of thousands.

German rocket scientist Wernher von Braun (arm in cast) surrenders to US Army counterintelligence personnel of the 44th Infantry Division in Reutte, Bavaria, in May 1945. Von Braun later played an integral role in the US space and rocket programs. Photo courtesy of NASA.

It was Moscow’s own version of Operation Paperclip that had sent the US scrambling to enlist as many Nazi scientists and engineers as it could. Washington was willing to overlook their egregious crimes because the battle lines were shifting. With the defeat of Hitler, America’s World War II ally, the Soviet Union, had instantly replaced the Third Reich as its primary enemy, and the two sides were now locked in a technological arms race that would ultimately bring the world to the brink of nuclear annihilation.

Origins of Operation Paperclip

Operation Paperclip began in the summer of 1945. However, Washington’s plans to exploit technologies developed by the Nazis had been underway since before the Allies fully liberated Europe.

According to Annie Jacobsen, author of Operation Paperclip: The Secret Intelligence Program That Brought Nazi Scientists to America, the British and Americans created the Combined Intelligence Objectives Sub-Committee (CIOS), an intelligence organization of more than 3,000 technical experts, in 1945. CIOS was tasked with collecting Nazi military research and materials in liberated territories. Initially, its chief objective was to gather information on special weapons — especially nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons. The US knew Nazi scientists had begun a nuclear program, and had already discovered stocks of chemical and biological munitions. CIOS agents worked with special reconnaissance teams to locate and secure these weapons and their delivery systems (and/or their blueprints), as well as the men who had developed them.

A 46-foot, 14-ton captured German V-2 rocket is launched during a test firing at White Sands Proving Grounds, near Las Cruces, New Mexico, in May 1946. The long-range liquid-fuel rocket was developed by German engineer Wernher von Braun, who in September 1945 came to the US as a technical adviser to the United States Army's missile program. AP photo.

By March 1945, the end of the war in Europe was finally in sight. The last German offensive had been thwarted, the Allies had crossed the Rhine in the west, and the Red Army had crossed the Oder River in the east. With Berlin now encircled, British, American, and Soviet troops closed in to deliver the final death blow to the Third Reich.

Then, suddenly and unexpectedly, the Americans halted their advance. Supreme Allied Commander Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower told Soviet leader Joseph Stalin that Berlin would be his for the taking. The British were incensed, but Eisenhower was already looking beyond the end of the war in Europe.

By that point, CIOS operations had revealed Germany’s military industrial complex to be staggering in scale and innovation. Nazi scientists and weapons engineers were much further along in their research than their American counterparts. While logistical and resource constraints prevented the Nazis from completing many of their most ambitious projects, they had pioneered a number of significant technologies, including the first combat jet, air-to-air missiles, and the impenetrable Tiger tank armor.

From left: Dr. William H. Pickering, director of the Cal Tech jet propulsion lab; Dr. James Van Allen, chairman of the physics department at the State University of Iowa; and Dr. Wernher von Braun, director of the development operations division of the Army, are seen at a news conference at the IGY headquarters in Washington, Jan. 31, 1958. AP photo by Bill Allen.

Having ceased major combat operations, the Allies made acquiring those technologies a top priority. While the Red Army was busy fighting for Berlin, Allied operatives got to work tracking down and arresting Hitler’s scientists, determined to beat the Soviets to the punch. The Americans formed the Joint Intelligence Objectives Agency (JIOA) to gather and review dossiers on hundreds of Nazi scientists and engineers, then recruit the ones deemed useful, move them to the United States, and, at least initially, put them to work in the war against Japan.

What Was Operation Paperclip?

Paperclip was originally called Operation Overcast. Under that name, the mission was to capture and interrogate 100 prominent Nazi scientists and leverage their expertise to expedite the defeat of the Japanese Empire.

In March 1945, CIOS agents made an accidental discovery that quickly changed and expanded the mission of Overcast. It began when a lab technician at Bonn University (in the German town of Bonn) found a crumpled document floating in one of the school’s toilets. The document turned out to be the so-called “Osenberg List,” a register of prominent Nazi scientists and engineers who, in 1942, had been moved from the war’s front lines to begin developing new weapons for the German Reich.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower gets a warm handshake from Alabama Gov. John Patterson, left, after arrival in Huntsville on Sept. 8, 1960, for the dedication of the George C. Marshall Space Flight Center. Wernher von Braun, director of the center, stands center. AP photo/BHR.

Created by German scientist Werner Osenberg, the list included only the names of scientists and engineers who had been thoroughly vetted to ensure their political ideology aligned with the Nazi regime. After being plucked from the toilet in Bonn, the list eventually found its way to US Army Maj. Robert B. Staver, an intelligence officer assigned to Operation Overcast.

The Osenberg List proved an invaluable resource for Staver and his team as they raced to capture Nazi scientists and engineers before they could be recruited by the Soviets. It also provided Staver with the intelligence he needed to expand the scope of the mission. Because the CIOS had uncovered enough evidence to show that the US was lagging far behind the Germans in many fields of research, Staver implored the War Department to recruit hundreds of the men named in the Osenberg List and relocate them to the US as soon as possible.

In July 1945, the Joint Chiefs of Staff released a top secret memo titled “Exploitation of German Specialists in Science and Technology in the United States.” The memo was never shown to President Harry S. Truman. In it, the Joint Chiefs described “desired” Nazi scientists as “chosen, rare minds whose continuing intellectual productivity we wish to use.”

German rocket expert Wernher Von Braun is shown Aug. 5, 1955, at the Pentagon in Washington. Von Braun had been working on a smaller model of the US Army's "Corporal" guided missile. AP photo.

It was no secret that most of those “rare minds” were war criminals, but that didn’t stop the War Department. Overcast was soon renamed Operation Paperclip, for the paper clips attached to the dossiers on the Nazis with “troublesome” records. Despite their records, most were still offered employment by the American government and approved for relocation to the United States as “War Department Special Employees,” according to Jacobsen.

President Truman approved the operation in August 1946, “provided they were not known or alleged war criminals,” according to Jacobsen. The Army and the OSS (forerunner agency to the CIA) circumvented this provision by simply ignoring their recruits’ deep ties to the Nazi regime. To that end, it was helpful that most of the Nazis themselves spent the rest of their lives whitewashing their own history.

The Soviet Union’s Operation Paperclip

Though the Soviet Union was an ally during World War II, the British and Americans saw the writing on the wall. They wanted to prevent the latest in supersonic rockets, nerve gasses, and jet engines from ending up in Stalin’s arsenal, but doing so would prove to be no small task, as the Red Army was just as hell-bent on scooping up Nazi tech.

Kurt H. Debus, a former V-2 rocket scientist who became a NASA director, sits between US President John F. Kennedy and US Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1962 at a briefing at Blockhouse 34, Cape Canaveral Missile Test Annex. Photo courtesy of NASA.

The Soviet version of Operation Paperclip was called Operation Osoaviakhim. Its objective was to move Nazi scientists and engineers to the USSR, along with their families, laboratory equipment, and other work materials. In some cases, the Soviets moved entire research facilities — including the Mittelwerk V2 rocket factory and the Luftwaffe’s aviation test center — from occupied areas into Soviet territory. Similar to the Americans, they euphemistically referred to the recruits as “Foreign Experts in the USSR."

Unlike with Operation Paperclip, however, the Nazi scientists captured by the Red Army were treated like criminals. They weren’t given the option of staying in Germany, let alone employment contracts. Instead, Moscow considered their work on behalf of the Soviet Union to be war reparations.

On Oct. 22, 1946, the Red Army, under the direction of the Soviet Union’s Interior Ministry, began implementing a carefully orchestrated plan to move Nazi experts in the fields of optics, aviation, chemical engineering, and other technology sectors eastward into the Soviet Occupation Zone. Upwards of 6,000 Germans were whisked out of their homeland on freight trains in a single day.

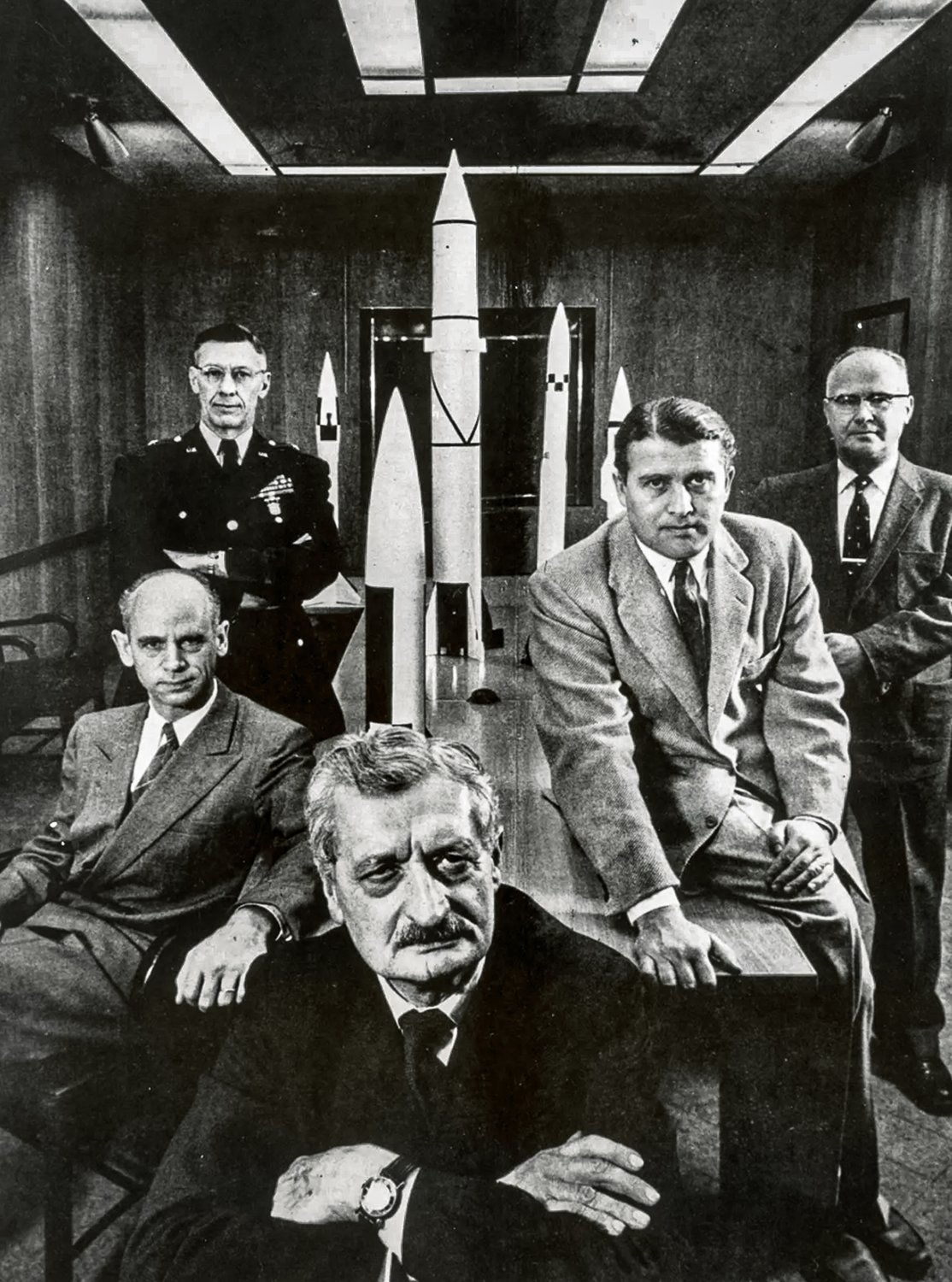

Operation Paperclip officials and participants: Hermann Oberth (foreground), Ernst Stuhlinger (seated left), US Army Maj. Gen. H.N. Toftoy (standing left), Robert Lusser (standing right), and Wernher von Braun (seated right). Photo courtesy of NASA.

Many of the forcibly relocated Germans were accomplished scientists or engineers who had been prominent members of the Nazi Party. As vassals of the Soviet Union, they would be crucial in the development of advanced turboprop engines, the Soviet Space Program, and even (some believe) the Kalashnikov AK-47 rifle.

The Success of Operation Paperclip

At the top of the Osenberg List was Wernher von Braun, who had served as the technical director of the Peenemünde Army Research Center in Nazi Germany. In that role, von Braun had overseen the development of the V2 rocket. After the war, he and his team — along with hundreds of other Paperclip recruits — were offered contracts to resume their work in the US as “War Department Special Employees.”

Von Braun and his team of Nazi rocket scientists arrived at White Sands Proving Grounds, New Mexico, in 1946, long after the war in the Pacific had ended. The rest of the Paperclip recruits were dispersed to various other facilities across the country, including Fort Bliss in Texas and Wright Field in Ohio. They were contracted to work in the US for just a short period — between six months and a year — but the resettlements turned out to be permanent.

Members of the German rocket team who worked on rockets for Army Ordnance under Paperclip are shown at White Sands Proving Ground, New Mexico, in 1946. Photo courtesy of NASA.

As the Cold War threatened to escalate into World War III, the recruits’ Nazi backgrounds became less important. What was more important was that the United States military needed their skills and knowledge more than ever — and, most importantly, so did the Soviet Union. In other words, were they to become free agents, they’d find plenty of job opportunities on the other side of the Iron Curtain.

Von Braun eventually became the director of NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center. He helped design the Saturn V rocket, which would take American astronauts to the moon and win the Space Race. And he wasn’t the only former Nazi with a very questionable past to play a central role in America’s Cold War strategy.

Operation Paperclip Declassified

Many of the scientists and engineers who came to the US via Operation Paperclip had worked directly with high-ranking Nazi officials, including Heinrich Himmler (head of the Nazi SS), Hermann Göring (head of the German Luftwaffe), and even Hitler. Some were themselves members of the SS, and a few were even tried for war crimes at Nuremberg.

Dr. Wernher von Braun, left, briefs President John Kennedy, center, and Vice President Lyndon Johnson at the assembly plant of the huge Saturn rocket on Sept. 11, 1962, at Huntsville, Alabama. AP photo.

For example, Arthur Rudolph, another Nazi scientist who helped develop NASA’s Saturn V rocket, had been director of Mittelwerk, an underground, high-tech German weapons factory and subcamp of the Buchenwald concentration camp. Some 20,000 inmates died at Mittelwerk. After a former camp inmate wrote a book condemning Rudolph in 1979, the US government finally launched an investigation. In 1984, he returned to Germany and renounced his American citizenship to avoid a trial.

There was also Hubertus Strughold, who as the Luftwaffe’s medical chief conducted human experiments on inmates at the Dachau concentration camp. After being relocated to the US, he helped design the pressurized suits and onboard life support systems for the Gemini and Apollo programs.

Georg Rickhey, the former head of the Mittelwerk camp, was the only Paperclip recruit who ever faced a formal trial. In 1947, he was extradited from Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio, to Germany for the Dachau Trials, where he was indicted for working with the SS and the Gestapo. It was alleged that he witnessed extrajudicial executions at Mittelwerk, but he was ultimately acquitted.

Although a lot of information about Operation Paperclip is now viewable to the general public at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., much of the paper trail remains classified. The full scope of the program — and the true histories of all the men it brought to the US — may never be known.

Read Next: How White Sands Missile Range Launched the Atomic Age

Randall Stevens is a military veteran with more degrees than he knows what to do with. He enjoys writing and traveling, and has an unnatural obsession with Harry Houdini.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.