Operation Remorse: How British Spies Conducted Economic Espionage in China During World War II

First of the Force 136 recruits, also known as the Operation Oblivion group, in Darwin, Australia. Back row (left to right): Douglas Jung, Jim Shiu, Norm Wong, Hank Wong, Louey King. Front row: John Ko Bong, Ed Chow, Roy Chan, Wing Won (in front), Norm Low, Roger Cheng, Tom Lock, Vincent Leung, Ray Lowe. Photo courtesy of the Chinese Canadian Military Museum.

Walter Fletcher was deemed unfit to serve in the British Armed Forces during World War II and was such a nuisance to Baker Street that any jobs he had requested that involved physical effort were denied. Colin Mackenzie, the head of Force 136, the Far East branch of the Special Operations Executive (SOE), once referred to Fletcher as “gloriously fat.” All 280 pounds of him requested special aircraft accommodations to be prepared in advance since he took up two seats on a flight’s manifest. His physicality differed from what was typically seen throughout the ranks of Britain’s elite paramilitary unit — but his wit as a snarky businessman was unmatched.

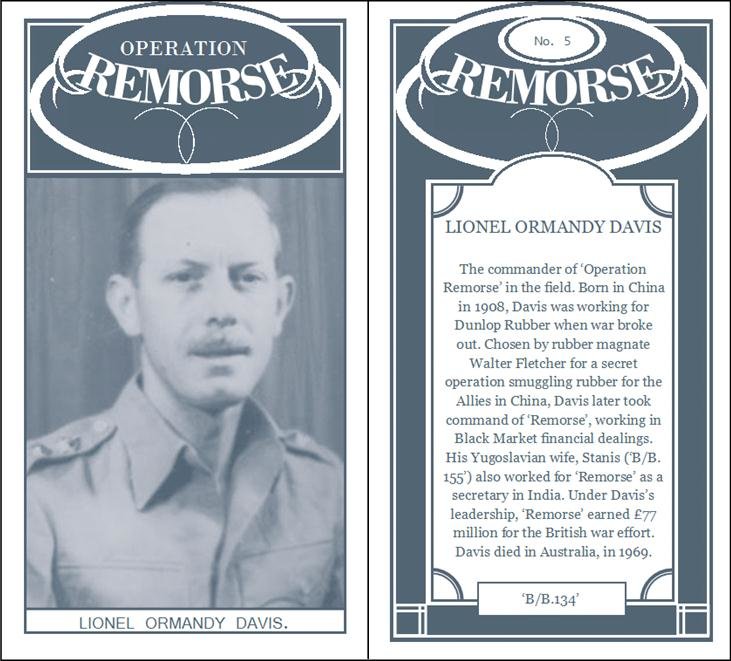

Fletcher was not well liked, but he was resourceful. Hugh Dalton, the Secretary of State for War, called Fletcher a “thug with good commercial contacts.” When he pitched the idea to run a covert economic espionage mission to manipulate exchange rates on the Chinese Black Market, his expertise was worth the risk. Codenamed Operation Mickleham then later Operation Remorse, Fletcher’s program in the initial stages went from sheer failure to among the most successful economic missions of the war, establishing influence in Hong Kong and funding other covert schemes.

The Bank of England provided Fletcher, who built a reputation as a wealthy rubber trader, with 100,000 pounds on Sept. 15, 1942. His bold moves for the next two years involved smuggling rubber from Japanese-controlled Indo-China, and his calculations were met with considerable losses. Internal reports authored by SOE officers were convinced their early predictions of Fletcher — the “Tragicomedy” — were correct.

As his reputation faltered, the Ministry of Supply demanded results. A lesser man would have given up, but Fletcher, both stubborn and determined, took economic intelligence learned during Operation Mickleham and adapted to the currency exchange rates to make profit.

“Then he went up to China and started negotiating in strategic materials, funny ones like tung oil and things like that,” Mackenzie told the Imperial War Museum. “Then he went on dealing in diamonds, watches, whatever the warlords wanted.”

Fletcher employed a seasoned team, including Frank Ming Shin Shu, also known as “Mouse,” one of his most trusted contacts. Shu bought £500,000-worth of Indian rupees at a lower official rate only to resell them at an inflated price on the Chinese Black Market.

“We had a very good accountant in London, John Venner, and he helped: even in the early days I had £20,000 of diamonds across my desk in one go,” Mackenzie told the Imperial War Museum. “One estimate is that the net profit was worth £77 million [£2 billion].”

Not all of the money was invested in back-end deals that filled their pockets. In April 1945, a force of 5,500 French soldiers across eight different locations were low on food and medical supplies and lacked blankets and clothing. Over the next six weeks, some of the funds from Remorse were diverted to purchase 93 tons of aid.

“A better job was done by Mr. Davis’s organisation than could have been achieved by the combined resources of the American and Chinese services of supply,” said a British ambassador in 1945.

B. S. van Deinise, a civilian and advisor of the mission, penned a memo that determined Operation Remorse was the “masterkey” for further intelligence actions in China: “I wanted to point out that the Masterkey should be made available to some of those who want to peep in and out of various compartments without attracting undue attention.”

The billion pound endeavor, hidden behind the auspices of bank statements and a covert paper trail, was only revealed to the general public after several intelligence activities from organizations like the SOE were declassified during the 1990s.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.