These Rescuers Traveled 1,500 Miles Through the Arctic with 400 Reindeer to Resupply Stranded Whalers

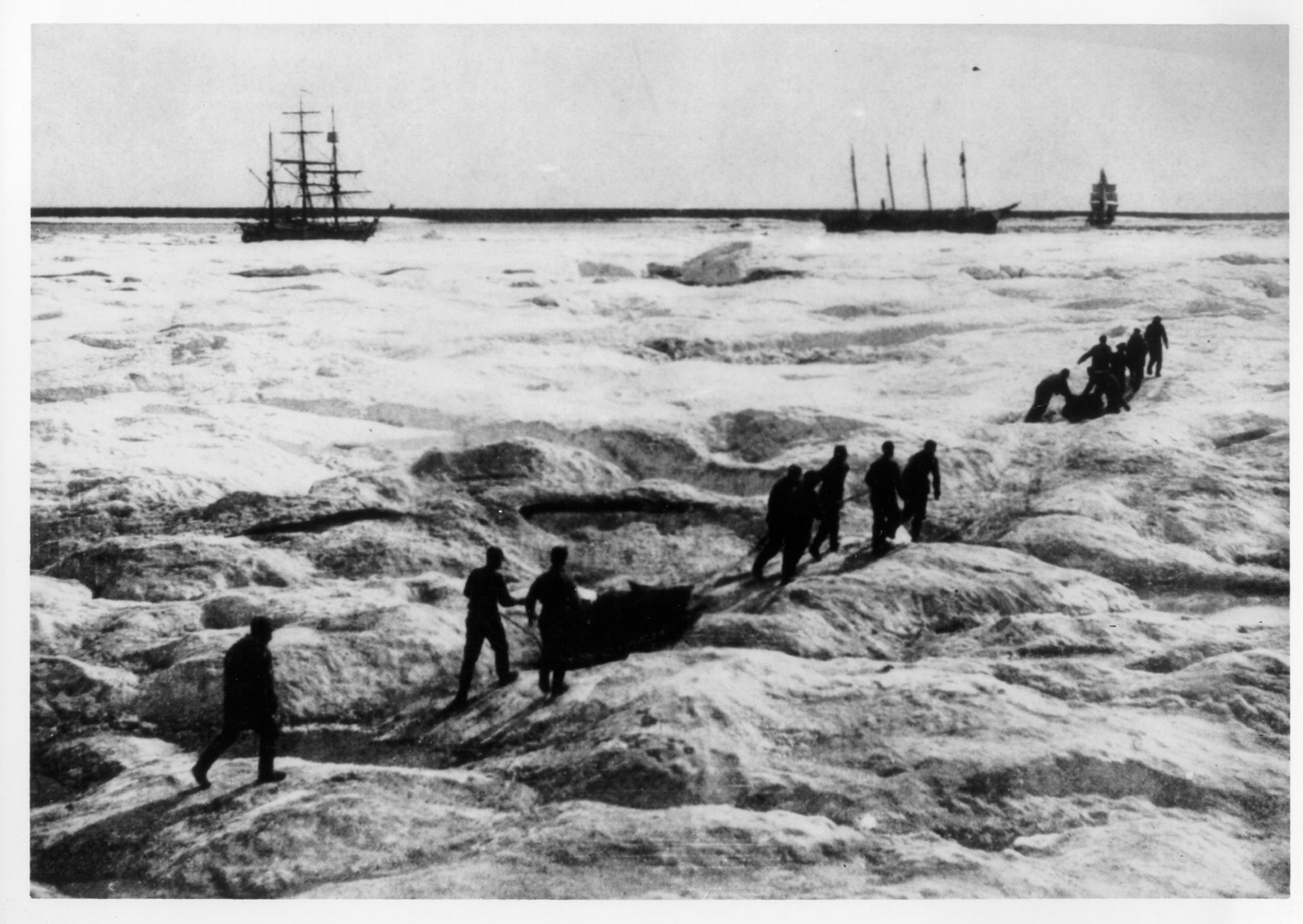

1897 Overland Relief Expedition approaches whalers trapped in the Arctic ice. Photo courtesy of the U.S. Coast Guard

Eight whalers and 265 men were stranded in the Arctic ice fields near Point Barrow, Alaska. From the top of the world the ship’s captain feared the worst. His crew was in danger of starvation, as they didn’t have enough food to endure the winter. In November 1897, President William McKinley had ordered the USS Bear — a dual steam-powered sailing ship and forerunner to modern icebreakers — to launch a rescue party.

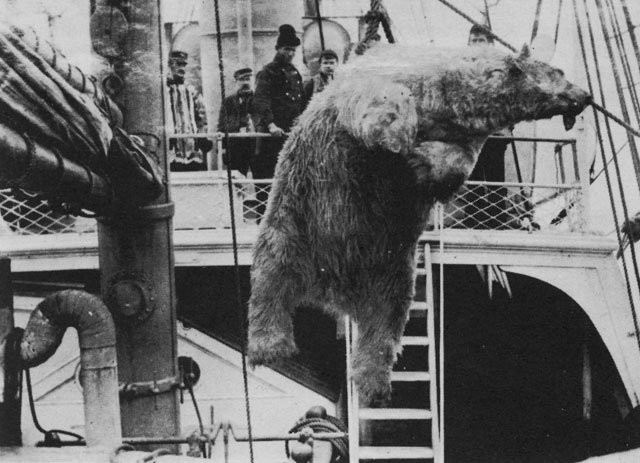

The Bear had just returned from its annual Bering Sea patrol. The perilous seafaring conditions tested the merits of its sailors, members of the US Revenue Cutter Service — the predecessor of the US Coast Guard — responsible for patrolling between 15,000 and 20,000 nautical miles of Alaskan coastline. As experienced as they were, the icy wasteland was wild and vast. Although the Bear had successfully rescued the surviving members of the Greely expedition 13 years prior, this mission presented an entirely new set of challenges.

The fall season was nearing its end, and the ice was too thick for the Bear to conduct a sailing rescue through the open ocean. Roads and railroads were nonexistent, and the Wright brothers hadn’t yet invented the first powered airplane. The only means of travel was over land using equipment such as snowshoes, kayaks, and skis as well as pack animals such as sled dogs and reindeer.

The Overland Relief Expedition, as it was later famously called, was daunting. The voyage was 1,500 miles through the unforgiving Arctic frontier. Capt. Francis Tuttle, the Bear’s skipper, asked for willing volunteers only. Executive officer and 1st Lt. David H. Jarvis took command of the mission. The two other officers were 2nd Lt. Ellsworth Bertholf and US Public Health Service Surgeon Samuel Call. They were later assisted by three others: W.T. Lopp, the superintendent of the Teller Reindeer Station; Charlie Ariserlook, a native reindeer herder; and F. Koltchoff, an enlisted sailor.

As the shore party landed near the village of Tununak on Dec. 16, 1897, the men were covered from head to toe in fur, with their faces exposed only where not covered by facial hair. Their caravan packed 1,500 pounds of food and supplies onto four sleds pulled by experienced huskies. A Russian guide and four Eskimos joined the expedition but took refuge near a camp in Cape Blossom after only a few days. Jarvis’ team crossed the frozen tundra and braced negative-15-degree gales during a blinding blizzard that moved in on Christmas Day. The severe conditions only temporarily stalled their efforts because timing was of the essence.

Huskies with scrapes on their paws were swapped for new dogs at aid stations to get fresh legs on the trails. The men’s minds couldn’t wander as they might have facing boredom aboard their ships; this journey was far too arduous to think of anything other than navigating onward. Jarvis made contact with a man called Mr. Tilton who was a third mate aboard the Belvedere, one of the eight whaling ships, which had taken aboard the crews of both the Orca and the Freeman. Those ships were either damaged or abandoned, and thus the rescuers sensed the urgency. In January 1898, the snow was too deep even for the sled dogs, and the men could only traverse through the snow with snowshoes.

“We had to make the next village, some thirty-five miles away, for it was out of the question to pitch a tent in such weather,” Jarvis’ log reads. “Tramping alongside the sleds and beating ourselves to keep warm, there were times when we anxiously looked for the protecting ice of Cape Nome. In the middle of the day we would see the sun, a red ball through the driving snow, but everything else on a level was a winding, blinding sheet. As we worked along, seeing nothing, buffeted about by the fierce gusts, it seemed as if we would certainly pay dearly for our temerity. In the afternoon the storm suddenly lulled, and we found ourselves under the lee of Cape Nome. We now breathed easier, and several hours later made our camp at the village of Kebethluk, on the west side of the Cape.”

On Feb. 3, 1898, at the Teller Reindeer Station, Jarvis ultimately decided the last leg of 800 miles toward Point Barrow was to be supported with a herd of 438 reindeer and 18 deer-drawn sleds. “Though the mercury was -30 degrees, I was wet through with perspiration from the violence of the work,” Jarvis later recounted in the final days of the Overland Relief Expedition. “Our sleds were racked and broken, our dogs played out, and we ourselves scarcely able to move, when we finally reached the cape [at Pt. Barrow].”

The mariners arrived to meet the surprised whalers after 99 days. “When we greeted some of the officers of the wrecked vessels, whom we knew, they were stunned; it was some time before they could realize that we were flesh and blood,” Jarvis recalled. “Some looked off to the south to see if there was not a ship in sight, and others wanted to know if we had come up in a balloon. Had we not been so well known, I think they would have doubted that we really did come in from the outside world.”

The impossible distress call was answered with 382 reindeer delivered out of the original 438. The most daring rescue in the history of the Arctic was accomplished through the efforts of a handful of men who didn’t know the meaning of failure. The following summer, the Bear sailed to Point Barrow and rendezvoused with the rescuers, legends in the crew’s eyes, who had miraculously survived without casualties.

President McKinley recommended Jarvis, Bertholf, and Call for the Congressional Gold Medal — an honor now shared with the likes of George Washington and the Wright brothers and groups such as the American Red Cross and the 65th Infantry Regiment.

After the historic mission, writings from Jarvis’ journals discussing his experiences provided further insight into one of the most polarizing figures belonging to the Long Blue Line.

“If you are subjected to miserable discomforts, or even if you suffer, it must be regarded as all right and simply a part of life; like sailors, you must never dwell too much on the dangers or sufferings, lest others question your courage.”

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.