Silver Wings, Silver Hair: Liberty Jump Team Takes Paratroopers of Yesteryear on a Wild Ride

The author in front of the “Southern Cross,” a C-47 troop transport like one of the 2,000 planes that dropped thousands of American paratroopers over Normandy on D-Day. Photo by Julia Akoury.

CORSICANA, Texas — We are flying on “jump run,” cruising at about 100 mph in a World War II vintage aircraft dubbed “Southern Cross,” a C-47 troop transport like one of the 2,000 planes that dropped thousands of American paratroopers over Normandy on D-Day.

We are about 1,500 feet above ground level, three times the altitude that D-Day paratroopers had jumped from to minimize exposure to Nazi ground fire and anti-aircraft artillery. The higher altitude for our plane is set to leave a safety margin for a reserve-chute deployment. A breeze from the open rear door keeps the tubular cabin of olive-drab steel and aluminum cool. The engine racket is deafening.

“On your feet!” the jump master, an active-duty Green Beret named Kris, shouts.

We clamber off the aircraft’s deck. I am the last jumper in my stick — a squad-sized team. Inside the aircraft jump order, I am just ahead of retired Army Col. Stu Watkins, a Vietnam War veteran, a man I had last jumped with nearly 50 years earlier. I am a couple of birthdays shy of 70, and Stu won’t hit 80 for years yet. The jumper in front of me is Klinton Jackson, a youngster of 56 from Keller, Texas, a trucking executive by way of the 25th Infantry Division from the 1980s.

“Hook static lines!” Kris shouts.

We hook our static lines to the long steel cable that spans the cabin’s interior like a clothesline.

“Check equipment!” the jump master shouts.

“Sound off for equipment check!” he adds.

“Okay!” six jumpers shout back in chorus. We each tap the leg of the jumper in front of us.

“One minute!”

For any who remember Band of Brothers, Steven Spielberg and Tom Hanks’ HBO miniseries about the Easy Co. paratroopers of the 101st Airborne in World War II, this safety ritual may look familiar.

The epic Emmy-winning series adapted from the Stephen Ambrose book is compelling history. But to really understand jumping from a perfectly good airplane full of paratroopers, you have to be in the airplane.

The C-47’s vibration, twin-engine roar, and cold rush of wind can only be experienced firsthand, hands clenched to the door, knees in the breeze. Near sunset on a cool evening in a week punctuated by thunderstorm and tornado warnings, we were on our final jump run to finish out “Operation Lone Star” with the Liberty Jump Team in Corsicana, Texas, deep in the oil patch outside Dallas.

Jump Master Kris shouts final jump commands above the din.

“Stand in the door!” and “Go!”

First jumper is out, and the rest of us follow in 1-second intervals. Jackson is in the door, then I am. The prop blast and breeze are blowing my cheeks sideways, my boots are set, my hands are on the door.

When I jumped with Stu in Cold War Germany, he was a 28-year-old captain recently awarded the Silver Star from adviser duty with Vietnamese paratroopers for Military Assistance Command-Vietnam. A tall, lean Texan, he is little changed nearly 50 years on. Col. Watkins remains a steady hand and cool head. He somewhat resembles Star Trek’s Jean-Luc Picard character, only Stu is the real thing — a flesh-and-blood leader. He invited me to return with him to Normandy if I refreshed my jump skills.

My bride, Julia, calls Stu “the gateway drug.” His invitation accounts for why I am in an aircraft training with the Liberty Jump Team, a nonprofit organization that performs highly authentic, military-style airborne operations for air shows, commemorations, and other teachable moments of history in classrooms and at special events.

“We’re not re-enactors,” Stu says. “We act.” Meaning everything about a parachute drop is real.

We hit it off in the real Army, even though Stu was an officer, and I was a buck sergeant. Rank flattens on skydiving teams, and we made a lot of free falls together and toasted our small victories with good German beer.

Once, while we were loitering in Strasbourg, France, on a three-day pass, the best idea Stu and I ever had at the same minute was a snap decision to not join the French Foreign Legion.

On a lark, we’d stepped into the centre recrutement de la Légion étrangère and listened to a harrowing pitch from a Belgian pit-bull terrier disguised as a recruiting sergeant. Had we left the US Army for that reckless adventure, I never would have met Julia, the girl I would always want to marry. Oddly, that decision brought us all together at a Texas airfield nearly 50 years later.

Little in life is ironic, but it can be fateful. Stu and I reconnected on Facebook after a couple of decades because Julia and I traveled to France in 2018 to pay respects to my Airborne heritage during a D-Day commemoration in Normandy. D-Day is the Airborne’s national legend as Iwo Jima is for the Marines. On June 6, 1944, 13,000 American paratroopers dropped in France to initiate the liberation of Western Europe from Nazi tyranny. Our Allies and all service branches made the D-Day victory, but American and British paratroopers were the first in.

In the decades since World War II, D-Day ceremonies evolved into weekslong celebrations for veterans, NATO troops, history buffs, and local survivors and descendants. Remembrances, battle re-enactments, parades, reunions, and toasts mark the “Day of Days.” Ceremonies honor the sacrifices of D-Day fallen, with heads of state paying respects at cemeteries near Omaha and Utah beaches, as well as at Juno, Gold, and Sword, the other three Allied landing beaches. Ceremonial parachute jumps by active-military and commemorative groups are key events.

For days, canopies blossom and paratroopers from active-duty American, British, and French units and from other Allied and NATO forces drop from the sky. Starting in 2006, the Liberty Jump Team began writing its own chapter of Airborne legacy by bringing WWII veterans to Normandy, all expenses paid, said Jil Launay, an LJT co-founder and daughter of a paratrooper officer. Most team members are paratrooper veterans or served in other military units and branches, and they come to jump.

The group also hosts speaker banquets. After our class of students and refreshers completed jumps from a Cessna light plane, we were waiting for the big bird, the C-47. Meanwhile, at a dinner to mark our progress, we got to hear from a real-life D-Day paratrooper, Sgt. Daniel McBride, a 101st Airborne Division veteran whose unit, the 502nd Parachute Infantry Regiment, was “first cousin” to the Band of Brothers of the 506th PIR.

McBride, of Silver City, New Mexico, is 97 years old. He is long lived despite three Purple Hearts earned between D-Day and the Third Reich’s defeat.

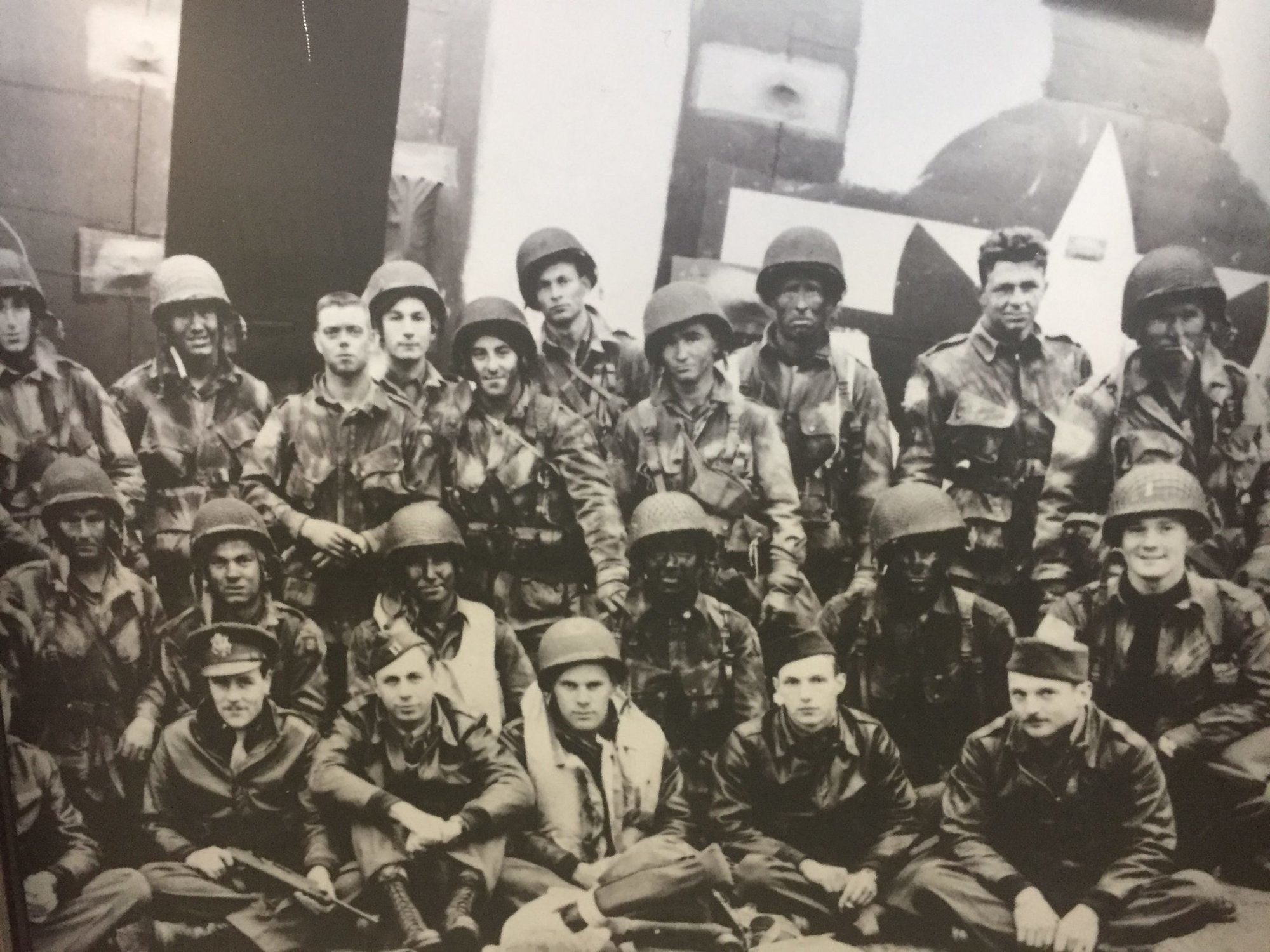

McBride lifted off for D-Day with his buddies from the 101st Airborne Division aboard a C-47, the two-engine workhorse of the Allied Command. Earlier on June 5, McBride and his “Screaming Eagle” buddies received a special visitor: Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, overall commander of the Allied invasion of Western Europe, Operation Overlord.

“He asked me if I was afraid, and I said, ‘No,’ because I wasn’t,” McBride recalled at the dinner hosted by Veterans of Foreign Wars Post 3066 in Corsicana, Texas. McBride added that a famous photo of Eisenhower fist pumping while he chatted with 101st paratroopers involved praise for fishing back home, not a battle cry.

A few hours later, around midnight June 5-6, the fleet of C-47s carrying the Airborne troops flew into fog, scattering planes across a sky full of flak, with Nazi anti-aircraft artillery cracking with pops and bangs, throwing shells that tore into aircraft, crashing some in fiery blazes, though most made it through.

“I looked up, and I saw France coming at me. I looked down, and I saw canopy.”

“I was third in the door, and the pilot was already swerving,” he recalled. “Maybe 300 feet altitude. […] I looked up, and I saw France coming at me. I looked down, and I saw canopy.”

He was hanging upside down, one of his jump boots having tangled in harness straps called risers as he was going out the door. Then, nothing.

“I don’t know if I was knocked out 10 seconds, or 10 minutes.” He came to, he said, feeling utterly alone.

He spied a German helmet moving in the hedgerows. “I traded one of my hand grenades for his MP-44.” Seizing the machine pistol from his erstwhile foe, McBride was re-armed. As with many paratroopers, much of his gear, including his compass, was lost in the opening shock and descent. Sometime before sunrise, he connected with a buddy and a lieutenant, who tried to get their bearings.

“Far as I can tell, I am almost nearly positive that we are somewhere in … Europe,” the lieutenant quipped.

“We spotted a 1936 Ford painted with camouflage,” McBride recalled. “We thought it might be the French Resistance we heard so much about.” Next, they spotted the driver’s German helmet, and McBride’s buddy made a killing shot with his M1 Garand.

“The rear door of the car came open with this squarehead armed with a handgun getting out, and I opened up with the MP-44. It fired four rounds and stopped, but they must have all hit him.”

McBride took the German’s pistol, a 9 mm Luger. They commandeered the vehicle and later found the town of Sainte-Mère-Église — the first town liberated in Normandy.

“That’s all we did on D-Day,” he concluded in a masterpiece of understatement.

After his talk, McBride led the Liberty Jump Team and VFW veterans in a rousing rendition of the paratrooper anthem, “Blood Upon the Risers,” remembering every word of its many stanzas. Most of us only remember the chorus, “Gory, gory, what a helluva way to die, and he ain’t gonna jump no more!” — which is sung to the tune of the “Battle Hymn of the Republic.”

The room rose to its feet and gave a standing ovation for D-Day veteran McBride and the other honored guest, Gold Star mother Cindy Marsh-Dietz, mother of Danny Dietz, one of the Navy SEALs killed in Operation Red Wings, recounted in the book and film Lone Survivor.

The atmosphere on a commemorative team such as Liberty Jump Team is military but without being militaristic. Students and refresher jumpers include veterans whose experiences range from nonconflict eras to combat from Vietnam to endless post-9/11 deployments and points between. Civilians can enroll as military history buffs, descendants, and documentarians and are welcome “to an experience that will test their limits, mentally and physically.”

During a weeklong class, students learn how to land safely via Parachute Landing Falls, or PLFs. Students also learn how to exit a military aircraft in flight and “how to jump from a perfectly good airplane.” Which raises the question, “Why?”

“There were three things I wanted from the Marine Corps,” Mike Algeo, a millennial veteran, said. “I wanted to graduate boot camp and then go overseas. My third goal was to go to Jump School at Fort Benning, but that’s a hard billet to get in the Marines.”

In the 1980s, Jackson, the trucking-company owner, wheedled his commander in Hawaii about attending Jump School half a world away in Georgia until he finally got approved. He never got it out of his system. For Rob Bueno, who fought in Afghanistan and served in the 101st Airborne, jumping a D-Day vintage C-47 troop carrier represents reverence for his service history.

“When we arrived at the 101st Airborne at the 506th at Fort Campbell, you watch Band of Brothers all the way through and read the book by Stephen Ambrose. There is a test, and you’ve got to pass it.”

Tracie Hunter, Army daughter and Emmy-winning documentary producer, started a nonprofit that honors World War II veterans such as McBride and the memory of her grandfather, who was wounded in the Battle of the Bulge. Motivations for military-style jump training are passionate and intense.

“This is where I wanted to be,” Jack Jones, who served with the 82nd Airborne Division in the 1990s, said. “I want to be with people like I served with. These are the people I want to be with.”

Lead LJT trainers include Senior Jump Master Butch Garner and Senior Rigger Jim Micko, who teaches parachute packing. It’s serious business, with safety the sole focus for these seasoned Airborne veterans. “This is not (fantasy) paratrooper camp,” team literature states.

“We teach it the military way for good reason,” Garner, who graduated jump school at Fort Benning in 1964, said. “We teach it this way because it works. Our objective is to get you to the ground safely.”

Packing parachutes is a sweaty, knuckle-busting exercise in patience and anxiety management, which is why Micko sounds like he could do it during a thunderstorm in New York traffic.

“There’s a purpose for every step in the process,” he said, smacking a chute bag tight as if he were delivering a baby. “If you cut corners, bad things can happen.”

We learned to fold nylon panels over suspension lines, laid out neat. We stuffed folded canopy into a canvas bag, hooked suspension lines into loops, installed it all in harness, and tied it off with a surgeon’s knot topped by square knot. The static line, with its snap hook, finishes the job.

We were ready, except for practicing parachute emergencies to be avoided, such as tree, water, and power line landings, plus more PLF practice from a 30-inch platform.

“If you keep feet and knees together, you will almost certainly have a good landing,” Garner counseled while running students through PLF practice.

Age range at Liberty Jump Team’s training session ran from 30s to 70s, with team members such as my jump buddy, Jackson, in his mid-50s, right in the middle. The Texas trucker was ready to revisit his roots more than 30 years after the long Cold War. Nodding at the chute I packed with sweat, blood, and a few tears, Jackson asked, “Did you pack it right?”

I told him it was okay and that the rigger signed off on it. “Not what I wanted to hear,” Jackson said. “Tell me that was an outstanding pack job!” I told him exactly that.

“Gearing up” is a Zen trust exercise of hooking your buddy’s chute harness, leg straps, chest straps, and chest-mounted reserve. The jump master checks it all again. During the strapping, hooking, and checking, we missed lunch and sunk to the tarmac, hungry and a bit wrung out. Stu was outfitted in the WWII kit of his 82nd Airborne unit, the 508th, and I wore my old unit patch: 8th Infantry Division, Airborne. My bride, Julia, walked over to the hangar and handed Col. Watkins and me a pair of energy bars. She smiled, and like magic, we were revived by soy protein, chocolate, and caffeine. Did I say this was a love story?

Fortified, we were, like the 82nd Airborne and Liberty Jump Team motto says, ready “All the Way.” We waited to hear the same engine roar Dan McBride heard on an airfield in southern England on June 5, 1944, the powerful Wright Cyclones. And we heard them.

The C-47 Skytrain, restored to D-Day black-and-white striped marking on wings and fuselage, swooped onto the runway for the final jump of Operation Lone Star, March 26, 2021, more than 75 years after McBride’s “rendezvous with destiny.” Propellers feathered, and we walked to meet the plane. Once aboard, we heard what sounded like a series of backfires signaling the radial engines spinning up. On the floor, I backed my butt against the bulkhead of the pilot compartment.

“For the record, this is what we came to do,” I said, loud enough for my buddy Jackson to hear and nod in response.

We felt the aircraft speeding up down the runway, then lifting off, with fading gold sunlight illuminating the interior through plexiglass windows.

Close to the door, his WWII paratrooper helmet strapped tight, Col. Watkins smiled, the same serene smile I witnessed on jump runs nearly 50 years earlier.

Jump Master Kris made his way along the line, shouting, “Jumpers, on your feet!” We lurched up, keeping hands over our reserve chute handles.

“Sound off for equipment check!” Rays of amber light filtered through plexiglass windows. The air was cold, crisp.

“Stand in the door!” First jumper, grasping both sides of the door. And “Go!”

Standing. In. The. Door. Is a heady instant, an amygdala rush of high terror, that brain component that screams “You have no business being here!”

Next, I’m in rushing air, and I look up to check a green nylon canopy that blossoms like a giant mandala. The lines are slightly twisted, so I bicycle with my legs the way I was trained to in 1973, and last week, and the thing straightens out nicely. At a little above 1,000 feet, sudden silence and cool breeze hits me in the face. A panoramic view of Earth rotates beneath my jump boots. Exhilaration flows through the pores … even if you are 68 years old, like I am. Back under canopy, in the heady performance of confident youth. Living the dream, with eyes on horizon, I guesstimate last seconds, put feet and knees together, and drop to Earth, collapsing in a heap, hitting terra firma like a lineman sacking the quarterback.

My buddy Jackson, his gear bundled, trudges my direction and calls out, “You good?”

“All okay,” I answer. We plod toward the hangar at dusk, feeling our age a bit.

The next day, a blue-sky Saturday, we line up as many of us did in service a long time ago. Our Liberty Jump Team wings are pinned to our chests by Sgt. Daniel McBride, veteran of D-Day, Holland, the Defense of Bastogne, and the capture of Hitler’s Eagle’s Nest.

McBride saluted, shook hands, and said, “Congratulations. Proud to know you.”

With our silver wings, both old and new, we were qualified to return to Normandy and jump in honor of the fast-vanishing veterans of D-Day under peaceful skies with our friends.

Read Next: World War II Veteran Vincent Speranza and His Legendary Airborne Beer Story

Dennis Anderson is a licensed clinical social worker at High Desert Medical Group. An Army veteran and retired journalist, he deployed with California National Guard troops to cover the Iraq War for the Antelope Valley Press. He specializes in veterans and community mental health issues.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.