‘I Just Disobeyed the Order’: The Incredible Story of Capt. Paris Davis’ Medal of Honor

Paris Davis, a Green Beret Captain in Vietnam, killed or shot at least 20 enemy soldiers, rescued four other Americans while under fire, and led the defense of a camp against a force of at least 250 in June 1965. President Joe Biden approved a long-delayed Medal of Honor for Davis.

Outgunned 3-to-1, with all of his men injured and dozens of them dead, a young Special Forces captain was ordered to withdraw from a vicious ambush in a Vietnam rice paddy.

“Sir, I’m just not gonna leave,” then-Capt. Paris Davis radioed back to the colonel who gave the order. “I still got an American out there.”

During the opening minutes of the ambush, three Americans had been pinned down, including the team’s medic, Spc. Robert Brown. Half a day later, he was still in the open, shot through the head but alive.

Again the colonel, circling in an aircraft overhead to direct air support for Davis’ beleaguered team, gave him an order to retreat.

"He told me to move out,” Davis later said. “I just disobeyed the order.”

Medal of Honor

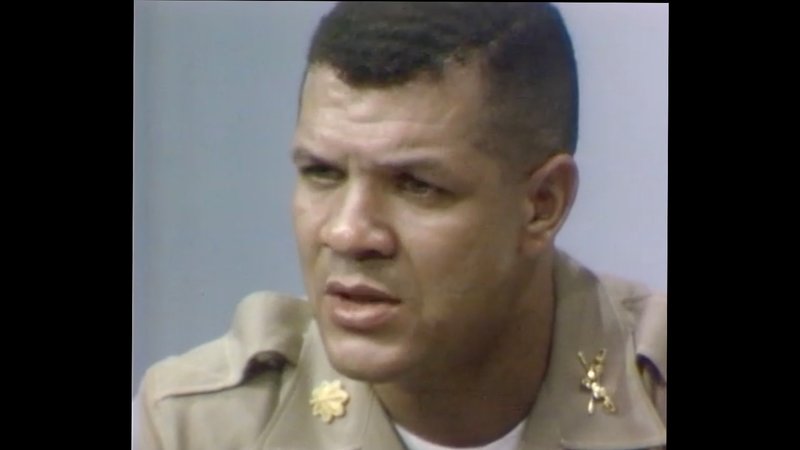

Then-Maj. Paris Davis in a 1969 television interview recounting his 1965 battle. Video capture from the University of Georgia archive.

Now Davis, one of the first Black officers to lead elite Green Berets, will receive the Medal of Honor for his actions during the 1965 ambush, a gunfight so intense that he later described it as “like being in the Fourth of July.”

President Joe Biden called retired Col. Paris Davis on Monday, Feb. 13, to officially tell him he had been awarded the nation’s highest award for valor. News that Pentagon officials had recommended him for the medal spread in November 2022, but a Medal of Honor is only official when approved by the president.

On June 18, 1965, Davis led his outnumbered force through a 14-hour battle and rescued four Green Beret teammates under direct fire.

Over the course of the gunfight, Davis was shot or took shrapnel eight times, but personally shot or killed at least 20 Viet Cong. Defending his positions and rushing forward to reach his wounded comrades, Davis engaged Viet Cong soldiers with virtually every weapon and method a Green Beret might need in a full career: He fired his M16, his pistol, a heavy machine gun, and a heavy mortar, threw grenades and dropped them into hidden foxholes, helped pinpoint airstrikes, and killed at least one enemy soldier in a hand-to-hand fight.

At least six times, Davis moved across open ground under fire to rescue four injured comrades, according to his own after-action report and the memories of his teammates.

‘Like Being in the Fourth of July’

Davis was a captain in the predawn hours of June 18, 1965, in command of a Special Forces team and three platoons of Vietnamese soldiers. He had played football at Southern University while attending on an ROTC scholarship and was one of the first Black members of the Special Forces.

In a 1969 television interview, Davis described being a Black officer in the then-mostly white world of Special Forces.

“It’s the third team that I had and I never had any negroes on my team. I’ve always had just whites. And we got along just splendidly,” Davis said. “I think one of the good things about a war or any type of crisis like Vietnam is the fact that people that are committed to it gel. There’s no race there. In the dark, brown is just as black or white as anyone else. We’re kin […] by virtue of being American citizens.”

The June 1965 battle at Camp Bong Son, Binh Dinh province, began in the early morning hours, just after Davis’ combined force of four Americans and roughly 70 Vietnamese returned from a raid on a Viet Cong camp. The soldiers had surprised the Viet Cong on the raid, wiping out dozens of soldiers in their beds and as they fled, including a senior commander.

Soon after they returned from the mission, a force of 250 to 300 North Vietnamese attacked the camp from positions surrounding the team.

In the opening minutes, Davis briefly broke away from the other three Green Berets to chase down a South Vietnamese commander who had fled the site of the ambush.

When he returned to his men on the edge of a rice field, he found a scene of carnage: All three Americans had been wounded and were stuck in exposed positions in the paddy. Staff Sgt. David Morgan had been stunned by a Viet Cong mortar round, though he would recover as the battle dragged on. Master Sgt. Billy Waugh and Brown, the medic, were gravely hurt and lying in open positions nearby.

Around them were dozens of their wounded and dead Vietnamese comrades.

Capt. Paris Davis escorting Gen. William Westmoreland, the commander of all US forces in Vietnam, on a tour of the Special Forces outpost in the weeks before the battle. Video capture from University of Georgia archive.

For the next 12 hours — as night gave way to day and then later back to darkness — Davis led a fierce, occasionally hand-to-hand defense of the position, fighting off waves of Viet Cong attackers, even killing one soldier with the butt of his rifle.

In his after-action report, Davis detailed a series of close, deadly engagements with enemy fighters:

- Early in the fighting, at least 11 Viet Cong tried to overrun his team’s trench. “I ran down to where the firing was and found five Viet Cong coming over the trench line. I killed all five,” he wrote. “Then I heard firing from the left flank. I ran down there and saw about six Viet Cong moving toward our position. I threw a grenade and killed four of them. My M16 jammed, so I shot one with my pistol and hit the other with my M16 again and again until he was dead.”

- He first looked for Morgan, who began yelling from a ditch, where he was stuck in a trough of human excrement used by farmers as fertilizer. He was also under sniper fire. Davis spotted the sniper, killed the shooter with his own rifle, then crawled to the shooter’s camouflaged hiding site and dropped a grenade in, killing two more Viet Cong. He then threw Morgan a rope and pulled him free of the muck.

- With Morgan recovered, Davis turned to Waugh, who was “submerged” in mud and vegetation, shot four times in the foot. Davis twice ran to the injured soldier before freeing him from vegetation. As he prepared to pull Waugh back, “the enemy again tried to overrun our position,” Davis wrote. “I picked up a machine gun and started firing. I saw four or five of the enemy drop and the remaining ones break and run. I then set up the 60mm mortar, dropped about five or six mortars down the tube, and ran [for Waugh].”

- After carrying Waugh to safety, Davis held off yet another Viet Cong assault with a machine gun. “I picked up the nearest weapon and started to fire. I was also throwing grenades. I killed about six or seven,” Davis wrote.

Spc. Robert Brown, who lay wounded in a rice paddy for the duration of the battle until rescued by Davis. Video still from University of Georgia archive.

Refusing To Retreat

As fighters dropped bombs, US helicopters came and went delivering ammunition and evacuating the wounded under heavy fire. As one landed, its crew chief had his nose shot off.

Waugh was evacuated with a shattered foot but returned to Vietnam a year later with a prosthetic before going on to a 40-year career as an agent in the CIA.

Another Green Beret, Sgt. 1st Class John E. Reinburg, arrived on the medevac helicopter that took Waugh and immediately joined the fight.

Reinburg first began running ammo to friendly Vietnamese troops, and then assaulted a machine-gun nest. As he charged, he was shot twice in the chest.

Under fire, Davis retrieved Reinburg and fireman-carried him 400 meters across the muddy rice field to safety.

Late in the afternoon of the fight, as American air support circled overhead, Davis was ordered to withdraw from the position by a colonel serving as a forward air controller overhead. But Reinburg needed to be evacuated, and Brown had not been recovered.

Davis told the air controller he would not leave until all were recovered.

“I guess I was real psyched up and I said some words over the telephone I don’t care to repeat, I guess it was because of the intensity of the situation,” Davis recalled (many field radios in Vietnam used handsets shaped like the telephones of the day).

A Vietnamese interpreter eventually found Davis. Though in shock from a badly mangled arm, the man told Davis “he alive” — the first word Davis had that Brown, the medic, was not dead.

As fighters dropped bombs, Davis crawled and made runs into the open to reach Brown, who he found in and out of consciousness. He had been shot in the head in the battle’s opening minutes and had lain in one spot for most of the 14-hour fight.

Davis examined the wounded soldier and discovered that his head had been bandaged by a Vietnamese medic who had since been killed in the fighting.

Finally, Davis carried Brown to safety as the fighting wound down.

The Medal of Honor hangs on recipient Maj. Gen. Patrick Brady’s chest during a military appreciation event at Clemson University, Oct. 31, 2019. Photo by Ken Scar.

Two ‘Lost’ Nominations

In the aftermath of the battle, Davis was nominated almost immediately for the Medal of Honor, but word came back that the nomination was lost in paperwork.

A second nomination by Davis’ fellow Green Berets also disappeared in the Pentagon’s bureaucracy.

Eventually Davis received the Silver Star, the military’s third-highest combat award. Among others decorated in the battle, Reinburg — the Green Beret who arrived mid-battle by helicopter, was shot in the chest and carried by Davis across the rice field — was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, which is second in precedence to the Medal of Honor.

Several of Davis’ white comrades began to suspect that racism was at the heart of the “lost” paperwork.

“What other assumption can you make?” fellow Green Beret Ron Deis told The New York Times in 2021. Deis was the youngest soldier on the team in 1965, the Times said, and was working as an air controller at the team’s main base, arranging for air support and communicating with Davis throughout the day.

Davis retired from the Army as a colonel and ran a small Black-focused newspaper in Virginia for 30 years. In recent years, a team of his supporters have rallied political leaders to revisit his case, and his review was fast-tracked in 2021.

“We all knew he deserved it then,” Deis told the Times. “He sure as hell deserves it now.”

Read Next: Hiroshi Miyamura, Awarded Secret Medal of Honor While Still a POW, Dies at 97

Matt White is a former senior editor for Coffee or Die Magazine. He was a pararescueman in the Air Force and the Alaska Air National Guard for eight years and has more than a decade of experience in daily and magazine journalism.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.