Walking Point: How Patrol Base Abbate Helps Veterans Find Their Tribe

Cody Morris spars with Garreth Hoernel at Patrol Base Abbate's "Fight Club" in July 2021, near Thompson Falls, Montana. Photo courtesy of Mark Cornellison.

Sweat shone on Cody Morris’ back, plastered strands of hair to his neck, and soaked the red bandana tied around his head as he held his boxing gloves in a defensive position. It was about 95 degrees in Thompson Falls, Montana, and the late afternoon sun had effectively transformed the black wrestling mats into a skillet.

With controlled swiftness, the 28-year-old Marine Corps veteran raised his left knee and smacked his sparring partner with his padded shin.

A moment later Simron Biant, a combat engineer in the US Army, got his revenge, landing a kick against Morris’ arm with a satisfying thud.

“There ya go,” Morris said good-naturedly.

Morris and Biant were among the dozen veterans and active-duty service members to set up camp in the dusty hills of western Montana the weekend of July 11, 2021, for Fight Club, the second of several retreats organized that summer by Patrol Base Abbate, a nonprofit dedicated to giving veterans a place to rest, reconnect with their warrior spirit, and rediscover their purpose through interest-based clubs.

Fight Club focused on developing martial arts skills, particularly through Brazilian jiujitsu and muay thai. Morris, however, told Coffee or Die Magazine he was new to sparring and rolling around on mats. He signed up for Fight Club simply because he’s high energy and missed “getting rowdy with the boys in the barracks.”

“Growing up, I never really had a family, and the Marine Corps gave me the family I always wished I had,” Morris said.

He and his sister bounced between foster homes whenever their mother wound up back in rehab. In 2011, he left for the Corps and never looked back. That is, until he finished his service and realized how difficult finding camaraderie in the civilian world could be.

“Coming here and hanging out with everybody, I feel like I’m with family again,” he said.

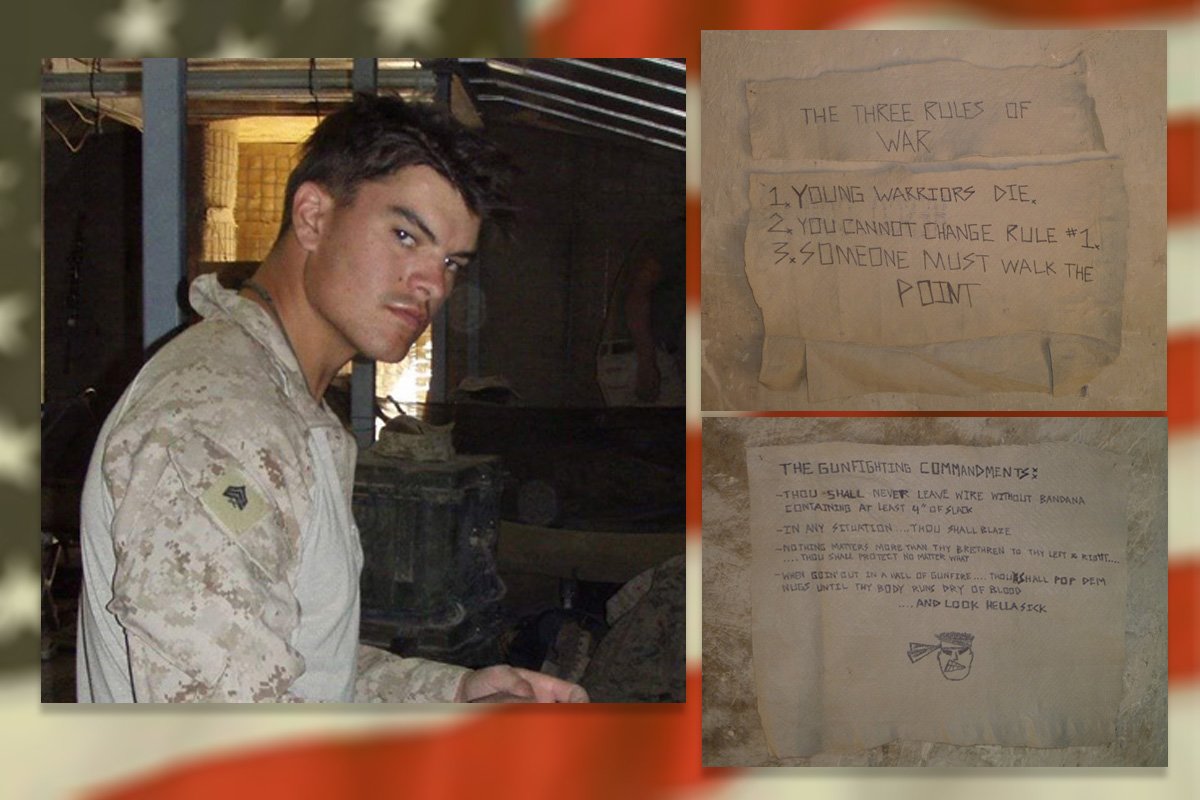

Patrol Base Abbate takes its name from Sgt. Matt Abbate, a scout sniper in the 3rd Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment, who was revered by his fellow Marines. He once said being a Marine was the only thing he’d ever been good at and famously penned three “Rules of War”:

1) Young warriors die.

2) You cannot change Rule #1.

3) Someone must walk the point.

Maj. Thomas Schueman, a platoon commander in the company Abbate supported, describes Abbate as fearless on the battlefield and a “modern-day Achilles.”

Abbate died during a firefight Dec. 2, 2010, in Afghanistan’s Sangin district. He was 26 years old.

Schueman returned from his Sangin deployment the following year and noticed many of his Marines were struggling with the transition to civilian life. He gained a greater understanding of those difficulties while studying veteran trauma narratives at Georgetown University in 2018, and by 2020, the idea for a virtual and physical community for veterans was underway, named in honor of Abbate.

With the help of a Marine Corps veteran who donated the use of part of his western Montana property, the nonprofit set up a physical patrol base in the summer of 2021 and hosted five retreats: Book Club, Fight Club, Strength Club, Hunting Club, and Music Club. Clubs, retreats, and regional chapters are free and open to all veterans, no matter how they served.

That’s huge because with many nonprofits catering to combat and special operations veterans and to wounded warriors, Schueman wanted to open the gates to everyone. Period.

“If you raised your right hand and said you would die for the Constitution of this country, you can come here,” Marine Corps veteran Mason Rodrigue said.

Rodrigue walked point the weekend of Fight Club. He joined the Marines in 2016, deployed to Syria, and “didn’t handle coming home well,” Rodrigue told Coffee or Die. His personal life spiraled out of control and he went back to the drawing board to figure out who he was and what he wanted his future to look like. He started writing — mostly poetry and fiction — and discovered Schueman’s popular Instagram page @kill.z0n3, where literature is a frequent topic. When PB Abbate’s inaugural retreat was announced, Rodrigue knew he had to get to Montana and meet other veterans at Book Club.

“It was really important for me to get up here and meet these people in person that I had made these online connections with and talk about this common thing we had together, which was writing,” he said.

At the end of the inaugural retreat, Rodrigue said it became apparent that someone needed to hang back and guide the following groups through the experience. So he stepped up. As someone who left the Marine Corps as a lance corporal, Rodrigue couldn’t believe he now found himself leading retreats and making a difference. He knows firsthand the struggle of service members and veterans pondering whether or not their efforts were worth it or wrestling with feelings of guilt or inadequacy because they didn’t see combat.

“I went to the Middle East, and I didn’t get the combat I thought I would get,” Rodrigue said. “I struggled with that when I came home, and I’ve realized that wallowing in this idea of being ‘less than’ doesn’t serve the men whose legacy I want to uphold. […] I hate the idea that my brothers might feel that their service didn’t matter because it mattered to me. That is why this place means so much to me, and what we’re doing here means so much to me.”

The patrol base was a short but bumpy drive up the hill from the highway. At night, Fight Club participants slept in two large canvas tents, and during the day they grappled on a platform built by the group that had visited PB Abbate before them.

“There’s a service component out here,” Rodrigue explained. “The Book Club literally built the platform that the Fight Club is fighting on.”

Fight Club cleaned up the trash, stuffing broken-down cardboard boxes, Styrofoam, and plastic into the backs of cars and hauling the debris to the dump. It’s far from the typical retreat experience, but the men agreed that it gave them a sense of ownership in the base.

“I don’t know anybody that would enjoy making runs to the dump,” said Kyle Whited, a Marine Corps vet. “This is our patrol base. It falls on us to make it better, not only for ourselves, but for the other people that follow us.”

Whited also follows Schueman on Instagram, but unlike Rodrigue, he was an ambivalent attendee at the first retreat. He planned to be in Montana for the summer anyway, so he figured he’d sign up and see what PB Abbate was all about. Since he was driving from southwestern Ohio in his blue Toyota Tacoma (complete with a rooftop tent), he could leave if the retreat sucked.

“Here I am the second week, so I guess it didn’t suck,” Whited said.

With the assistance of energy drinks, the 6-foot-6-inch, bearded former embassy guard drove 28 hours straight to get to Montana. Given that inauspicious entrance, one might not have expected him to have such a calm, mountain-man aura about him. But Whited spent the weekend of Fight Club quietly preparing dozens of strips of bacon and massive piles of scrambled eggs on a propane stove for breakfast as the other guys sparred a few yards away, and plucking country folk songs on his guitar as background music to the nonstop chatter and coarse jokes.

“It was refreshing after being out [of the Marines] for about five years to see a group of guys just fall in on one another and immediately get to working together just like they’ve been doing a whole year of work up,” Whited said.

Everyone Coffee or Die talked to said they bonded with the other participants remarkably fast — even if it looked as though they were trying to murder each other on the mats.

“When I got off the plane, I was just like, Damn, I’m hanging out with the Marine buddies again,” Morris said. “I was a little nostalgic.”

Skill levels ranged from novice to brown belt to an assistant instructor with a black belt, said Nick Cimmarusti, owner and Brazilian jiujitsu instructor at Chicago School of Grappling. Cimmarusti had some exposure to BJJ in the Marine Corps. After returning from a deployment to Iraq in 2005, he had his own difficulties transitioning to civilian life.

“Even though I started training, I was still drinking more than I should have, hanging out more than I should have, and then a few years later my mother got killed by a drunk driver,” Cimmarusti said. “It really changed my perspective on drinking and my intentions on life and where I wanted to be.”

Martial arts helped him get through the next few years. Instead of drinking, he told himself to focus, just go to the gym, and get some exercise.

“Whatever happens, just go to the gym. Do that,” he said. “Eventually it got easier and easier to deal with.”

Now, he hopes to share that passion with other veterans, especially ones who might be fighting their own demons.

“When you’re training, you’re generally very focused, and it allows you to forget about the other stuff that’s happened, either in the past or around you,” he said. “So for a little bit of time, you get to step away from that. And then the physical aspect of it allows you to kind of just reset and then come back to those thoughts that may have been troubling you with a clear head.”

As Cimmarusti and his co-instructor, Garreth Hoernel, ran the guys through warmups and technical drills, they were amazed by the group’s passion and dedication. Sweat streamed down faces like tears and dripped from the tips of noses, yet everyone wanted to keep going. Just one more round.

Hoernel was the lone civilian at PB Abbate that weekend. A friend in the Marine Corps had connected him with the group so he could help out during Fight Club.

“It puts wind in my sails and gives me more purpose, realizing that what I’m put on this earth to do is empower others through the martial arts,” he told Coffee or Die.

The patrol base offered a special environment for training: the open air, the stately pines, and the towering mountains.

“This is some magical place here,” Cimmarusti said.

On their final evening at the patrol base, Cimmarusti summoned the rest of the group onto the mats and delivered PB Abbate’s farewell address.

“Get back on patrol,” he read, imploring them to continue their service and inspire other veterans. “We are not broken, damaged, or fragile. We are warriors.”

Participants were then asked to complete one more task: filling a sandbag.

Filling sandbags is nothing novel for a veteran. It’s how you fortify your position and build your base.

But the mundane act took on extra significance during the first retreat, when Schueman wrote Abbate’s name on a sandbag.

“Fill your sandbag. Write someone’s name on it that you want to honor,” Cimmarusti instructed the men. “Honor the legacy of whomever you dedicate this sandbag to by choosing to live for them every day in a meaningful way. […] Stay in the fight and keep attacking.”

Rodrigue held a woven plastic bag open as Cimmarusti drove a spade into the rocky dirt next to the grappling platform. Dust billowed as he emptied the shovel into the bag. Finally, he tied it shut.

The rest of the group collected their own empty bags and scrawled names on them. They might not have known Matt Abbate personally, but everyone knew someone like him.

The men filled the bags for their families — by birth and by choice. For the lance corporal who inspired Whited to learn guitar, his own fingers silenced after a fatal mission in Helmand province, Afghanistan. For the battle buddies and leaders who took their own lives after coming home.

One by one, they placed the sandbags around the perimeter of the mats and punched them flat, then dusted off their hands as the shadows grew longer around them.

The Fight Club inductees rose with the sun Monday morning. They sipped coffee and cleaned up the base. They crammed all of their luggage into two vans and swore when someone opened a door again, triggering a booby trap that sent a backpack straight into the dust. The property owner’s pit bull, Basilone, came to see them off and bask in the farewell ear scratches.

It was a surprisingly difficult farewell for men who had only known one another for a few days. But they had formed a solid bond at PB Abbate, getting to express themselves in a judgment-free environment, to crack obscene jokes one moment and discuss deeply personal, complex issues the next.

“A patrol base is temporary,” Rodrigue said. “Everyone has to go home at some point.”

They piled into the vans, not knowing that they would continue their raunchy banter in a virtual group chat over the coming months, and check in on one another during the fall of Afghanistan. Many would honor Sgt. Abbate’s third rule of war by promptly starting their own chapters of PB Abbate across the country, walking point and bringing new veterans into the fold.

Rodrigue thought back to one of Schueman’s lectures from the first weekend.

“He talked about the fact that the military is tribal, and one of the struggles when they get out is that they lose a tribe,” he said. “But nobody owes them a tribe, you have to come find it. And I feel like everyone went up there, and they found their tribe.”

This article first appeared in the Spring 2022 edition of Coffee or Die’s print magazine as “Walking Point.”

Read Next:

Hannah Ray Lambert is a former staff writer for Coffee or Die who previously covered everything from murder trials to high school trap shooting teams. She spent several months getting tear gassed during the 2020-2021 civil unrest in Portland, Oregon. When she’s not working, Hannah enjoys hiking, reading, and talking about authors and books on her podcast Between Lewis and Lovecraft.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.