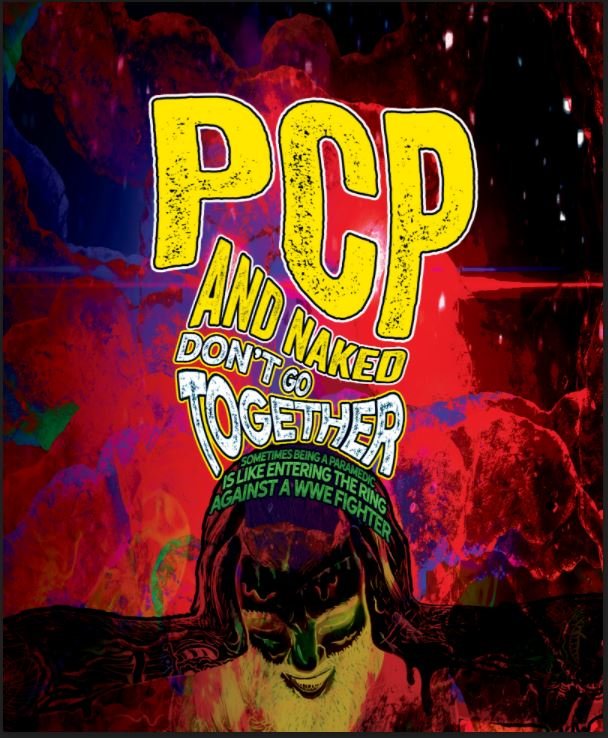

PCP and Naked Don’t Go Together: A Minneapolis First Responder’s Tale

The night began with an ominous dispatch: “Code three to the area for an adult male acting erratic.” Coffee or Die Magazine illustration by Josh Raulerson.

Storm clouds are hovering around the city of Minneapolis. It’s a warm, humid night, and several 911 calls are already behind me. My 12-hour shift started at 4 p.m., and it’s just past midnight when I start to heat my Tupperware dish full of mashed potatoes, bacon, and thin-sliced steak. Since dispatch posted us at a local firehouse, I have the rare opportunity to warm my meal before eating it.

“Seven-twelve, 700,” dispatch radios.

“Seven hundred, 712, go ahead,” I respond.

“Code three to the area for an adult male acting erratic,” dispatch calls back. There is a hint of humor in the dispatcher’s voice that makes me anxious. I look questioningly at my partner, Rachel.

“Caller is stating the man is naked and pounding on random front doors in the neighborhood,” the dispatcher says.

So much for dinner.

Rachel and I have worked so many shifts together at this point that we don’t really have to say what’s on our minds. She knows I’m feeling pure frustration at missing out on another meal.

We hop in our ambulance, flipping on the lights and sirens as we speed down the road. When emergency medical services are dispatched to the area of a call, it generally means that law enforcement needs to secure the scene. So we wait.

We park near a railroad crossing in an empty parking lot so we can see if anyone approaches the ambulance. It’s late at night, and some interesting characters roam the area. After what feels like hours, dispatch says that the scene is “kind of” safe and that police are trying to calm the patient. We can drive up at our discretion.

My partner drives the ambulance up the road a short distance, and we see a struggle between the police and a white male with scruffy, dark, curly hair. Several squad cars have their lights still flashing. Five officers are trying to hold down this man who appears to be, at most, 170 pounds.

The man is rambling indiscernibly. He is also naked and covered in sweat.

hallucinogenic effects. It distorts perceptions of sight and sound and makes the user feel disconnected and not in control. It is an injectable, short-acting anesthetic for use in humans and animals. US Drug Enforcement Administration photo.

Rachel pulls out the stretcher and lowers it to the ground while I try to help the police talk the man down. He is flailing like a fish as we try to keep him stationary. There’s a wild look in his eyes, and his pupils are almost completely dilated. He’s breathing rapidly; his skin feels hot to the touch. Scrapes, cuts, and bruises cover the man’s body — some fresh, some faded.

Reasoning with the patient isn’t working, and while his energy refuses to wane, we’re getting tired and running out of options. Rachel and I both know the man is in an excited delirium, and it’s a matter of time before his heart stops from the buildup of acid in his system. I pull out a syringe, attach a needle, and draw up some ketamine.

The ketamine will subdue the patient enough for us to get him into restraints — for both our protection and his. But while I’m trying to hold the man’s leg still to administer the anesthetic, he delivers an angled kick to my chest. My ballistic vest softens the blow, but I need backup. My partner switches positions with a police officer. We stabilize the man’s leg, and the needle finds its mark midline on his quad. I quickly administer the ketamine and hope that the medication takes effect quickly so we can get this man under control and keep him from dying.

We ease up and wait to see if the medication will work. Based on the patient’s Hulk-like strength, we assume he has consumed PCP, also known as angel dust, a powerful street drug that causes extreme hallucinations. Seconds feel like hours as the patient slowly loses strength, allowing us to hoist him onto the stretcher and put him in soft restraints.

His arms and legs are anchored to the stretcher now, and the medication is really taking hold. The patient’s manic state is slowing down, and we quickly get him into the ambulance. We are all drenched in sweat, eager to escape the humidity. We load the stretcher, and Rachel and I go to work on the sorely needed assessment.

When the patient was in excited delirium, his incredibly high respiratory rate was keeping the acid that had built up in his blood in check. Now that the ketamine has been administered, the patient’s respiratory rate will slow, preventing exhalation of the acid and potentially causing cardiac arrest.

Rachel works to dry the patient off in order to place the electrocardiogram leads. I get an IV in the patient and connect a 500 ml bag of normal saline, running it wide open. Next comes the sodium bicarbonate medication to combat the acid buildup. I administer it slowly as the patient weakly fights against the restraints. Because of the excess acid in the patient’s system, I don’t want to slow his breathing too much.

Rachel hops in the front of the ambulance, and two officers agree to ride with us to the hospital. The ambulance takes off with lights and sirens, informing the world we are on our way. I call in my report to the hospital and let them know we will need a stabilization room in the emergency department. Even though EMS workers in Minneapolis are equipped to handle and properly treat patients during calls like this one, hospitals have a wider array of medications to ultimately repair what is happening inside the body of a patient experiencing drug-induced excited delirium.

The patient eventually sinks into a comatose state while still breathing well on his own. His eyes flutter open occasionally, making me wonder whether he’s going to spring suddenly back into Hulk mode. It sounds crazy, but it’s happened before.

We pull under the hospital’s canopy, where a host of security and fellow paramedics are waiting. They had been listening in on our radio chatter and knew we might need help. When an excited delirium patient hits a certain point, EMS or hospital staff often have to take over the airway in order to prevent respiratory arrest, which would lead to cardiac arrest. Fortunately, that did not happen today.

As we walk into the rear of the ED, the stabilization team welcomes us. One of my favorite doctors is leading the team, and he asks the staff to quiet down so I can update them on the patient’s condition, what my team did to help him, and the overall contextual evidence we were able to gather. I give a detailed but abbreviated report as we move the patient over, and the ED team starts prepping the patient for further treatment. I grab a signature from the nurse who is officially taking over his care.

My partner and I walk the stretcher — with all the recently detached equipment strewn over it — back to the ambulance. The whole way down the hallway, we crack jokes about naked, sweaty dudes and how we hope there’s not a bad batch of drugs hitting the streets.

Some shifts, calls like these are dispatched all night long. Only a few hours more and we get to drive home and sleep away the day.

This article first appeared in the Summer 2021 edition of Coffee or Die’s print magazine.

Read Next: Prison Time for Man Who Tried To Gun Down 6 Federal Agents

Joshua Skovlund is a former staff writer for Coffee or Die. He covered the 75th anniversary of D-Day in France, multinational military exercises in Germany, and civil unrest during the 2020 riots in Minneapolis. Born and raised in small-town South Dakota, he grew up playing football and soccer before serving as a forward observer in the US Army. After leaving the service, he worked as a personal trainer while earning his paramedic license. After five years as in paramedicine, he transitioned to a career in multimedia journalism. Joshua is married with two children.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.