Another Feat of Klay: Marine Veteran’s Novel Achieves the Promise of his Short Stories

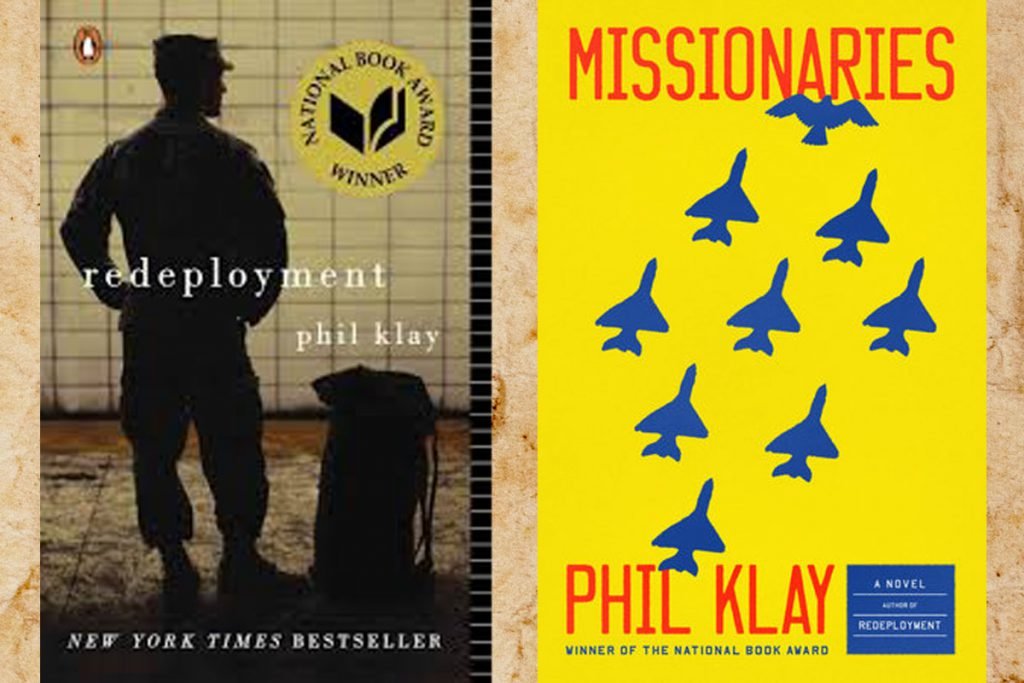

When a dozen short stories by a Marine veteran of the Iraq War were published as Redeployment in spring 2014, the collection, the writer’s first book, commanded critical and commercial attention.

Redeployment is mostly about people with Corps on their CVs, people with experience being in and coming back from combat. (Perhaps you read the title story the year before in Fire and Forget, a fine anthology of veterans’ fiction.)

The debut volume ended up on lists of the year’s “best” books, including this reviewer’s, made The New York Times bestseller list, and received publishing’s Oscar — the National Book Award for Fiction.

Now, former Capt. Phil Klay returns with his second book with a one-word title, Missionaries — a full-length novel with 112 more pages than Redeployment.

Can the short-story writer sustain high-quality writing and dramatic tension in a longer read? Is his second work worth waiting six and a half years for? Does he live up to the promise he exhibits in his first book?

Yes, to all three questions.

Klay, who earned a master’s in creative writing after he left the Marines, can create a multidimensional character you want to relate to. He can build a situation you want to stick with, even if the chance of a happy ending is slim. He does both in Missionaries — a word with the same syllable count as “mercenaries.”

The four main protagonists share a missionary zeal about their own dreams and professions. They’ve seen everything, good and bad, and want to know what’s next.

As they narrate Book I and Book II, each voice speaks alone in a separate chapter, sort of like a series of short stories. At least two chapters could stand alone. One is about a visit with a cancer-filled Uncle Carey, another about gruesome Helmand province.

“If there’s a heaven for limbs, a waiting room in paradise where the severed parts await reunion with their owners, we put in some work filling it up.”

Their tales evolve with hints that lead a reader to wonder how the four might collide or coalesce:

Sgt. Major Mason Baumer is a soldier and not your usual Klay Marine. Formerly a Ranger, he is a medic on a Special Forces team — having ascended to “a higher level of badassery” than mere Rangerhood. A Ranger is a gorilla, but “SF is an 800-pound gorilla that can dance ballet.”

At first he loves his job, even when he is slightly embarrassed by its side effects — which he admits in one of Klay’s comic comments:

“Before some raids — don’t laugh — but I’d have an OCB, which is the official DoD nomenclature for Out of Control Boner.”

But he begins to question the purpose of “the occasional mission” and his participation in it. “People told me I’d never understand sex until I’d done it, never understand combat until I’d been in it, never understand life itself until I was a father.”

After he realizes each, he has “no idea what to do with any of them.”

Now he prefers his strategy-over-tactics duty as the SF liaison behind a desk at the US embassy in Bogota.

Abel lives near La Vigia along the Colombia-Venezuela drug route. Here he and other villagers wait “like a pig facing a knife” for the next atrocity as “paracos and guerrilla and narcos and bandits and police and soldiers” and militias compete for their attention and assets. Abel himself did paramilitary work. It goes with the territory.

Although one of the thugs distinguishes himself because he “always took pity on the orphans whose parents he had killed,” the epitome of evil is “the pit bull couched to strike,” Jefferson Quesada.

“Before doing violence,” Abel says, “he’d talk nonsense to confuse and to justify.”

The four “missionaries,” each trying to determine what it means to be good and do good, become unwitting actors in the chaos of a contemptible Colombia.

Lisette Marigny is a journalist whose war reporting gives her a sense of belonging to a community, something she doesn’t find back in Pennsylvania — and “one of the things that helped me develop a feel for Afghans and for American soldiers, who have their own version of tribalism.” To her, being at home is being in a trap.

But Kabul bombings are getting old. “I’m tired of covering a failing war,” she admits, and considers an assignment in India. She decides to ask Diego, a former boyfriend who served with Mason, for career advice. He’s a counternarcotics contractor happily on the periphery of problems. (“We affect things on the margins.”)

She texts Diego. “Are there any wars right now where we’re not losing?”

He replies with a single word: “Colombia.”

And so she goes.

Juan Pablo followed his father into the Colombian army, and he believes he is the personification of stalwart. He is a reserved voice of reason (when the reason is his) who plays with Americans only because they come fully equipped.

You meet him at a dinner party in his home with his wife and his daughter, a university student who is considering an internship with a leftist professor in rural, poor Colombia.

“If her generation were ever so safe that they could look on mine with disgust, that would only mean that my life’s work had been successful,” he tells himself.

The lieutenant colonel allows his hosting an enlisted man to be irritating: “He is no suitable partner for me in any sense, and certainly not my social equal.” Mason arrives on time, “an irritating habit American military have.”

Dinner is served and after “leaving the women upstairs,” Juan Pablo offers Mason a cigar — the soldier holds it “awkwardly and lets too much saliva touch the quickly dampening edges.”

When Mason, who is experienced at both, suggests “mixing war and policing is dangerous,” Juan Pablo seethes. The assessment is “too stupid to take seriously.”

Of course he doesn’t say that aloud.

Book III is where the four characters come together, where the Klay plot culminates and converges.

“Writing only shakes the reader if they cooperate,” Lisette says, “put in the work to go past the headline and the lead and imagine their way into what you’re trying to tell them.”

Klay eases such cooperation. Known for literary fiction — for shelves in bookstores rather than drugstores — he shows an ability to create literary suspense. Thrillerish, even.

So how does Missionaries end?

The four “missionaries,” each trying to determine what it means to be good and do good, become unwitting actors in the chaos of a contemptible Colombia. Telling the resolution in this review would be a criminal act, and there’s enough of that in the book. Without the need for a spoiler alert, it’s safe to say somebody is swept away.

Juan Pablo is the last voice Klay introduces in the character lineup and has the last word in the novel. “Wars are not fought by armies,” he says. “They are fought by cultures.”

He ought to know. His new and admittedly mercenary role has support from China, the United Arab Emirates, Colombia, and the US. “What sits behind us is the entire civilized world.”

Missionaries by Phil Klay, Penguin Press, 416 pages, $28

J. Ford Huffman has reviewed 400-plus books published during the Iraq and Afghanistan war era, mainly for Military Times, and he received the Military Reporters and Editors (MRE) 2018 award for commentary. He co-edited Marine Corps University Press’ The End of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell (2012). When he is not reading a book or editing words or art, he is usually running, albeit slowly. So far: 48 marathons, including 15 Marine Corps races. Not that he keeps count. Huffman serves on the board of Student Veterans of America and the artist council of Armed Services Arts Partnership and has co-edited two ASAP anthologies. As a content and visual editor, he has advised newsrooms from Defense News to Dubai to Delhi and back.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.