Classic pink flamingo lawn ornaments roost in 2017 at the South of the Border tourist attraction in Dillon, S.C. Photo by Carol M. Highsmith, now in the Library of Congress.

In 1957, a 21-year-old art school graduate named Don Featherstone created his second major design for the Massachusetts-based lawn and garden decoration manufacturer Union Products: a three-dimensional plastic pink flamingo propped up by two thin, metal legs that could be plunged into soft dirt.

Featherstone’s duck and flamingo ornaments sold in pairs for US$2.76, and were advertised as “Plastics for the Lawn.” They became simultaneously popular and derided in the late 1950s and remain a recognizable species of American material culture.

Featherstone died this past June, but over five decades after he submitted his design, the plastic pink flamingo continues to grace American lawns and homes. While many are quick to label the plastic ornament as the epitome of kitsch, the flamingo has actually taken a rather tumultuous flight through an ever-changing landscape of taste and class.

All three of the ornament’s basic elements – plastic material, pink color and the flamingo design – have a particular relevance to the late 1950s.

The year 1957 was the year of Elvis Presley’s Jailhouse Rock and the ‘57 Chevy, of popular plastic toys like Wham-O’s hula hoop and the Frisbee – all icons of midcentury nostalgia. The late 1950s also witnessed the solidification of a commodity-driven suburban way of life, along with a host of new anxieties over class and status.

In the postwar era, cheap, sturdy and versatile plastics were becoming an increasingly popular material for mass-produced commercial products, from Tupperware to Model 500 rotary phones.

Design historian Jeffrey Meikle discusses how this era was referred to as “a new Rococo marked by extravagance, excess, and vulgarity.” Many design and cultural critics pilloried plastic for its ability to easily depart from established design principles, though consumers and manufacturers kept the craze going.

The fad was clearly waning by the 1960s. In a famous scene from The Graduate, actor Dustin Hoffman expresses disillusionment in the “great future in plastics.”

And then there’s the color pink. Art historian Karal Ann Marling explains that in the 1950s, pink was perceived as “young, daring – and omnisexual.” She points out that popular celebrities like Mamie Eisenhower, Jayne Mansfield and Elvis Presley loved to incorporate pink in their wardrobes, their bedroom decor and – in the case of Elvis – their cars.

Featherstone’s design wasn’t the first time flamingos swooped into American culture, either. In fact, Americans had long cherished the exotic bird, native to the Caribbean and parts of South America, and this love affair came to a head in 1957 with an explosion in popularity of Caribbean culture.

Caribbean-American pop star Harry Belafonte’s album Calypso, which contained the hit single Banana Boat Song (Day-O), dominated the Billboard charts in 1956. And as a 1957 LIFE Magazine cover story attests, Americans were flocking to Caribbean resorts in record numbers.

Jennifer Price wrote the most comprehensive essay on the plastic pink flamingo in her book Flight Maps. She details how 19th-century European and American settlers hunted flamingos to extinction in Florida.

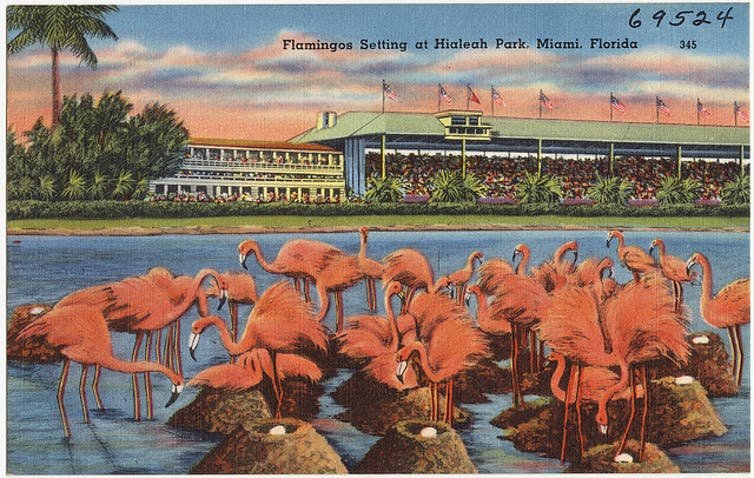

But as the state drew wealthy vacationers in the 1910s and 1920s, resort owners imported the pink birds to populate their grounds. They even named Miami Beach’s first luxury hotel “The Flamingo.” Soon, Florida and these exotic-looking birds became synonymous with wealth and leisure.

As the century progressed, the development of interstate highways and a rise in disposable income made Florida a practical destination for middle-class and working-class families. Vacation spots made accessible by the Interstate Highway System cashed in on the style and flair of the Caribbean fad. The flamingo was now associated with a region that was both exotic and affordable.

Despite the plastic pink flamingo’s resonance with so many things 1957, the ornament was almost instantly ridiculed as kitsch, which was a particularly damning designation given its habitat: the American lawn.

As one of the few outward social spaces in the privacy-obsessed architecture of suburbia, lawns were (and still are) subject to extreme social pressure. They were perceived as both a symbol of the American dream and a productive way to spend one’s newfound leisure time.

However, “Keeping up with the Joneses” was less about outspending your neighbor than it was about conformity and maintaining appearances. The preferred look of middle class lawns was well-manicured and free of ornament, with flowers abutting the house.

To homeowners’ associations, the plastic pink flamingo’s bright color and synthetic material was an affront to the middle-class yearning for sophistication (though a piece of pink plastic is no less “natural” than a lawn maintained by DDT and Miracle-Gro).

On the other hand – as Jennifer Price points out – working-class consumers tended to express themselves differently, favoring loud, playful and decorative schemes for their homes and lawn.

Flamingos sprouting from small lawns in Catholic neighborhoods seemed less out of place among concrete Virgin Mary statues and tiny St Francis fountains.

In the 1950s, publications like LIFE propagated a narrowly defined definition of middle class style and taste. So the display of the plastic pink flamingo in the 1950s and 1960s was perhaps not mere unsophisticated kitsch, but rather an overt rejection of the “middle-brow striving for the high-brow” lawn aesthetic.

While cultural critics like Gillo Dorfles have maintained that lawn decorations like garden gnomes and sculptured animals were an “archetypal image conjured up by the word ‘kitsch,’” a younger generation saw the plastic pink flamingo as a rebellion against the “stay normal” pressures of postwar suburbia.

Their camp appropriation of the plastic pink flamingos crossed the boundaries of good and bad taste, making Pink Flamingos a fitting title for John Waters’ 1972 transgressive film about two contenders for the title “filthiest person alive.”

Eventually, this transgressive power began to also wane, and the product faced possible extinction in the early 2000s due to the rising cost of oil.

Luckily the flock has survived (you can still purchase a pair for around $20 on Amazon). Today plastic pink flamingos have even been spotted gracing planters on a brownstone off Park Avenue in Manhattan, illustrating just how far the bird has migrated among American classes and tastes.

This story appeared first in The Conversation on July 22, 2015. The Conversation is a community of more than 135,400 academics and researchers from 4,192 institutions.

Read Next:

Coffee or Die is Black Rifle Coffee Company’s online lifestyle magazine. Launched in June 2018, the magazine covers a variety of topics that generally focus on the people, places, or things that are interesting, entertaining, or informative to America’s coffee drinkers — often going to dangerous or austere locations to report those stories.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.