The US Army’s Polar Bear Expedition and Their Fight Against Russia After World War I

After nearly three weeks of fighting “Bolos” in the wilds of North Russia, Olympia sailors appear tired and ragged but still full of élan. They have added improvised slings to their Mosin-Nagant rifles, which were likely made in the United States under contract for czarist Russia. Looking on are newly arrived U.S. soldiers of the 339th Infantry. Photo courtesy of the U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive. (https://www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history-magazine/2016/august/bluejackets-vs-bolsheviks)

Sir Ernest Shackleton, the famous Antarctic polar explorer, engineered canvas and leather boots to withstand subzero temperatures in the harshest climates on the planet. Shackleton’s boots were warm and easily compatible with skis and snowshoes. Through his methodical instruction, draftees from the US Army’s 339th Infantry Regiment of the American Expeditionary Force envisioned they were well equipped and well trained enough to handle the weather conditions in the Arctic Circle. They were wrong.

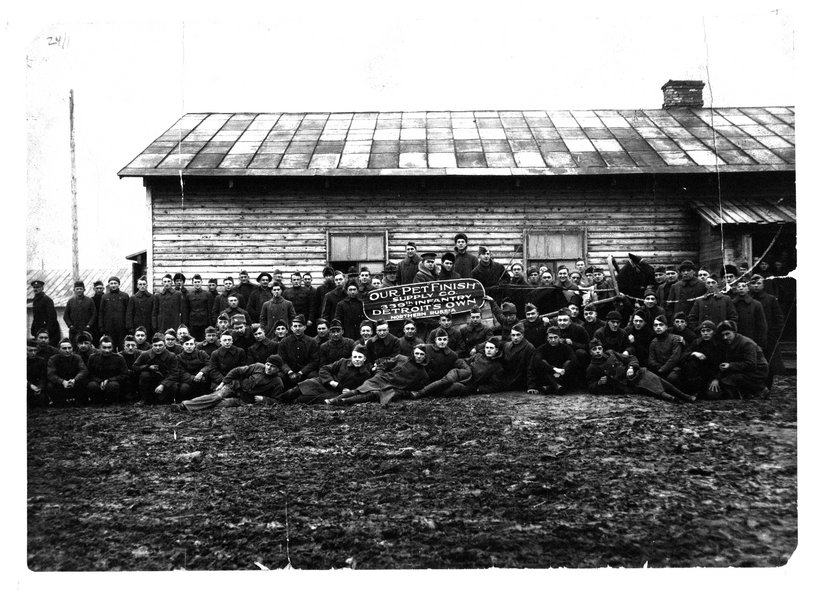

Four months prior to the World War I armistice, soldiers from the 339th — known to newspapers as “Detroit’s Own,” as more than 75% of their force hailed from Detroit, Michigan — were given unusual orders. Instead of deploying to France to endure the violence along the Western Front, President Woodrow Wilson tasked them with a special mission that required special training.

After the completion of their extreme cold weather course with Shackleton in London, one of two American expeditions was tasked with securing Allied stockpiles stashed in Siberian ports. The other was sent to protect the Trans-Siberian Railway to facilitate the evacuation of Czechoslovakian prisoners.

The Russian empire’s focus on World War I and its alliance with the Allies in the West had ceased after the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. The Soviet Red Army (Bolsheviks or “Reds”) had instituted a communist government and peace with Germany. The White Russians, or anti-Bolshevik forces, had received 600,000 tons of ammunition from the Allies to defeat the Germans prior to the Russian Civil War. These stockpiles were left unsecured, and in direct support of the French and the Brits, Wilson sent American troops into Russian turmoil with the intention of reopening the Eastern Front.

In September 1918, 5,000 soldiers from the 339th landed in Archangel, a Russian port on the White Sea, after an eight-day voyage aboard three camouflage ships. As they disembarked the USS Olympia, Michigan’s fight song, Victors, played by members of the ship’s band, echoed across the port.

Their determined smiles and first impressions of their newfound circumstances just beyond the Arctic Circle were replaced almost immediately as the first rush of cold air scraped across their faces. Their life in bitter cold was described as living in a nightmare.

“This is really the most godforsaken hole on Earth,” Lt. Charles Ryan wrote in his diary. “Never did I strike such a fine set of assorted odors. The people are filthy and seem starved to death.”

The subzero temperatures, sometimes as low as negative 65 degrees Fahrenheit, froze weapons and targeted open skin, causing frequent casualties of frostbite. A lack of medical supplies didn’t help the growing fear of contracting the Spanish flu, which would kill between 50 million and 100 million people worldwide. The ice was difficult to traverse, but the soldiers used reindeer sleds to solve that problem. They also used snowshoes to move through thigh-deep snow but could not escape the shivering cold of Russia’s “General Winter” — especially considering their sheepskin cold-weather gear wouldn’t reach their positions until October of that year.

They quickly termed their effort the Polar Bear Expedition, and themselves the Polar Bears, the only species that could survive in such harsh conditions.

The Polar Bears served under British command, and their defensive mission guarding the ports and railway system turned into offensive skirmishes and run-and-gun firefights against the Soviet Red Army and Bolshevik revolutionaries.

The soldiers who weren’t fighting for their lives enjoyed Charlie Chaplin movies, dances with American Red Cross nurses, and fresh showers and meals. “I made a hit with an eskimo girl [sic] spent the day riding around the Divina River with a Reindeer taking photographs,” Cpl. Fred Kooyers wrote in his diary.

Following the conclusion of World War I, morale was almost nonexistent. The Polar Bears remained in Russia, fighting and dying, with no real purpose as to why they were there in the first place. Sgt. Thomas F. Moran wrote in December, “We are fighting for British interest and spilling good American blood and wasting good American lives for a cause our government surely doesn’t understand.”

In January 1919, the Bolsheviks launched a weeklong campaign outnumbering the Polar Bears eight to one, forcing a deadly and costly retreat. The Bolsheviks camouflaged themselves in all white, ran through the snow like Yeti, the mythical snow monster, and engaged in bloody fighting with the Polar Bears. The battle left 29 Americans killed in action, 58 wounded, and another 19 considered missing in action. The regimental commander reported that those who were lost must have frozen to death.

“What is the policy of our nation toward Russia,” Sen. Hiram Johnson later commented to Congress when he learned of this incident. “I do not know our policy, and I know no other man knows our policy.”

Five months later, in June 1919, the Polar Bears — who were among the first and last Americans to fight on Russian soil — came home. The US Army retrieved 120 American soldiers who had been left behind in the fall of that same year. The Polar Bear Association formed in 1922, and the veterans of the Polar Bear Expedition continued to advocate against the reasoning whereby they were sent to Russia in the first place. The Polar Bear Association remained active in their search to find the Americans who didn’t return home. Their efforts lead to the recovery of 102 of their brothers-in-arms, but 27 remain missing in action to this day.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.