The Polygraph Machine Is a Debunked Science — It’s Also a $2 Billion Industry

Federal agencies continue to invest money in polygraph screenings for applicants, despite such tests being illegal in the private sector. Wikimedia Commons photo.

During Gary Gauger’s 1993 interrogation over his parents’ murders, police officers tried to convince him of his guilt. In their narrative, Gauger had bludgeoned his parents to death and slit their throats in a drunken blackout. When Gauger refuted the officers’ accusations, they went a step further and administered a polygraph test mere hours after Gauger had called them to report finding his elderly parents’ bloody and beaten bodies.

Police used the test against Gauger to obtain his tearful confession. “[Police] claimed that they had found blood-soaked clothes in Gauger’s bedroom; and they told him that he had failed a polygraph test which was, in fact, inconclusive,” the National Registry of Exonerations said.

A jury convicted him to death, and he served three years in prison before a judge exonerated him in 1996 after the true killers — members of the Outlaws motorcycle gang — were located on the word of a jailhouse informant.

Gauger’s case is one of several examples that highlight the unreliable science behind the polygraph machine. Polygraph testing results are not legally admissible in most courts, and the American Psychological Association says “most psychologists agree that there is little evidence that polygraph tests can accurately detect lies.”

Despite the fact that polygraph tests are widely considered unreliable, the federal government still administers them for jobs requiring special security clearances, spending over $2 billion on employee screenings. During these screenings, interviewers ask simple questions to establish a baseline, then advance to more complex questions. In this so-called control question technique, questions range from standard to purposely stressful, leading to questions relevant to the investigation. The tests measure several physiological indicators believed to be manifestations of deception: changes in blood pressure, pulse, respiration, and skin conductivity.

Both federal and local law enforcement agencies relied upon the machines after their invention in 1921; however, the polygraph’s reputation took a hit at the end of the 20th century.

“There is no evidence that deception produces a unique physiological reaction,” said Dr. Leonard Saxe — a social psychologist at Brandeis University — in a 1991 article, “Science and the CQT Polygraph – A Theoretical Critique.” He continued: “Polygraph tests do not assess deceptiveness, but rather are situations designed to elicit and assess fear. […] That a non-deceptive (innocent) individual would be highly anxious when answering questions about a crime that they are suspected of committing seems not to have been considered.”

Saxe helped research the validity of polygraphs for the National Research Council, a congressional think tank, in response to President Ronald Reagan’s push to screen federal employees using the test. He published his findings with the NRC for Congress in a 1983 report, leading to the nationwide passage of the Employee Polygraph Protection Act, which prohibited most private employers from using lie detector tests for pre-employment screening.

“Almost a century of research in scientific psychology and physiology provides little basis for the expectation that a polygraph test could have extremely high accuracy,” Saxe concluded.

A 1998 Supreme Court decision restricted courts-martial tribunals from using evidence obtained through polygraph tests, the opinion of the polygraph examiner, and any reference to the option to take or not take the test. The Supreme Court found polygraphs did not have “sufficient scientific acceptability to be relevant,” since they measure anxiety, not lies — something the test itself can trigger.

Anxieties played an integral part in a number of cases highlighted by the National Registry of Exonerations for convictions based on polygraph results. The Innocence Project, a nonprofit legal organization pursuing justice in wrongful conviction cases, has several instances showing the defendant’s state of mind during the polygraph was an important element of the results. Notable cases include Gary Gauger, Emmanuel Mervilus, and the Green River Killer.

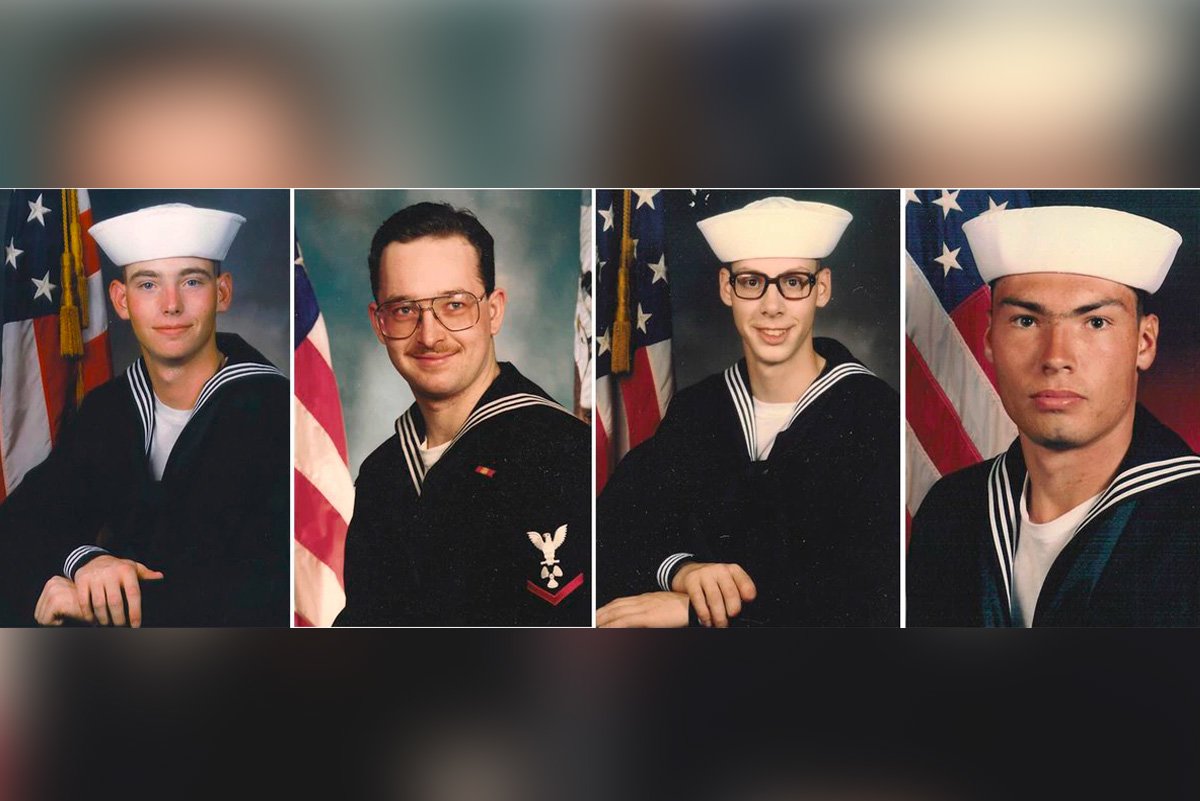

In a shocking example from 1997, a jury convicted four US Navy sailors, Derek Tice, Joseph Dick, Danial Williams, and Eric Wilson — known as the Norfolk Four — of the rape and murder of 18-year-old Michelle Moore-Bosko based on falsified polygraph results and police-coerced confessions. This was despite evidence that a different man — already incarcerated for a separate sexual assault — matched crime scene DNA and confessed to the murder. One sailor, so convinced of his own guilt, wrote a letter of apology to the victim’s mother. It took more than 20 years to exonerate them.

It gets worse.

The Green River Killer passed a polygraph in 1984, and because his results convinced police of his innocence, Gary Ridgway continued murdering women around Seattle and Tacoma for the next 20 years. He was convicted of 46 counts of murder in 2003, but police suspect his victim count is possibly as high as 80 or more.

Not only do defendants get railroaded by the polygraph, but victims as well. In the award-winning Oregonian investigative report, “Ghosts of Highway 20,” Marlene Gabrielsen recounts the events of 1977 after she told police that John Arthur Ackroyd, an Oregon state highway mechanic, raped her on the side of the highway. Instead of logging the evidence of Gabrielsen’s ripped clothes — which she preserved and gave to police — and a medical report evidencing the violence of the attack, the police administered a polygraph.

After being further traumatized from recounting her rape during intense police interrogations, Gabrielsen failed the 30-question test. Ackroyd passed his polygraph after police asked him only four questions. Later, Ackroyd went to prison for the 1978 murder of Kaye Turner, but police suspect him in three other women’s deaths, including that of his 13-year-old stepdaughter.

Though polygraphs have squarely been placed in the “debunked” category, law enforcement and federal agencies still insist on burning their budgets on polygraph screenings.

“It doesn’t matter whether the test actually works, just that it’s perceived as effective,” Vox reported.

The polygraph machine still sits in the CIA’s interview room because people believe it — it’s both a deterrent and a prop. Better methods are unlikely to emerge.

“The simple answer to the question of better methods is that there are [none],” Saxe told Coffee or Die Magazine. “The fundamental problem is that there is no unique physiological response to lying. […] Pinocchio is just a children’s story.”

Read Next: How Twin Convicts Beat a Death Sentence by Drinking Coffee

Lauren Coontz is a former staff writer for Coffee or Die Magazine. Beaches are preferred, but Lauren calls the Rocky Mountains of Utah home. You can usually find her in an art museum, at an archaeology site, or checking out local nightlife like drag shows and cocktail bars (gin is key). A student of history, Lauren is an Army veteran who worked all over the world and loves to travel to see the old stuff the history books only give a sentence to. She likes medium roast coffee and sometimes, like a sinner, adds sweet cream to it.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.