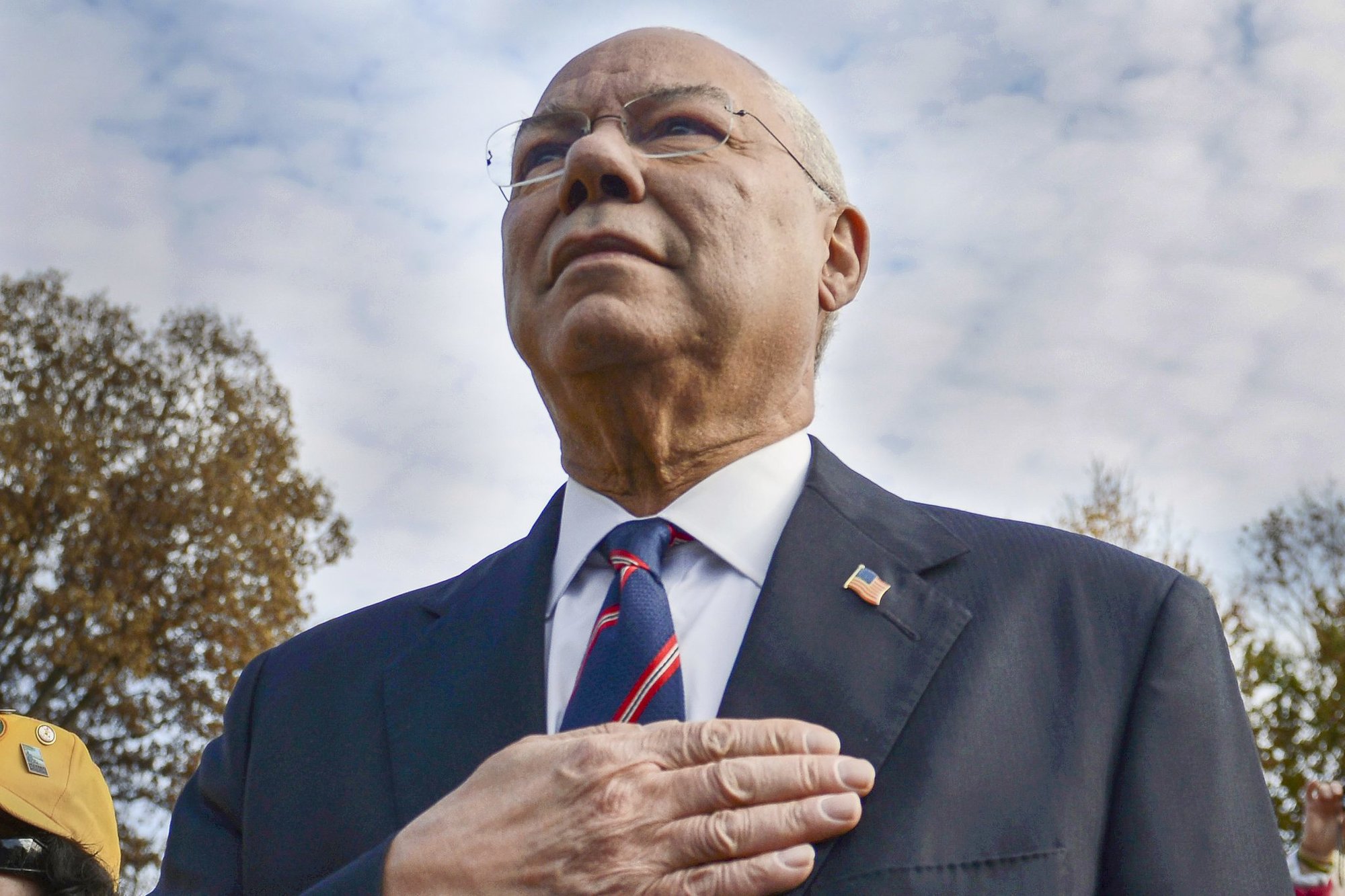

Retired Army Gen. Colin Powell looks toward the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in Washington, during Veterans Day observances, Nov. 11, 2013. DOD photo by Lisa Ferdinando.

The day after Gen. Colin Powell died at 84, I was eating chili at a dingy bar in Austin, Texas, when a haggard, middle-aged waiter appeared over my shoulder, inquiring to the Willie Nelson look-alike behind the bar, “Did Colin Powell die?” Willie confirmed he had, and the Texans immediately lamented the great stain of Powell’s decadeslong career of public service, recalling the day the nation’s first Black secretary of state testified on behalf of the George W. Bush administration at the United Nations, selling cherry-picked intelligence to the American people and the world and making the case for the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

Dispatched for his credibility as the sole, reluctant warrior in a cabinet stacked with reptilian plutocrats and chicken hawks, Powell helped sell a losing war that cost trillions of dollars, killed thousands of Americans and Iraqis, and pulled much-needed resources and attention away from Afghanistan, which recently moved firmly into the L column of America’s war record after 20 years of prolonged conflict.

While I couldn’t blame the gents at the bar for firstly associating Powell with one of the most regrettable episodes of his professional life, I appreciated that both men further qualified their comments: The man who rose from working-class, Jamaican American roots in the South Bronx to the highest levels of the US government was a great, benevolent leader who championed a military doctrine the United States should embrace if we ever want to win another war.

Powell, who graduated from City College of New York and earned his Army commission through the ROTC, conceived his template for military action based on lessons learned in Vietnam, where he served two tours of duty.

As chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) in the George H.W. Bush administration, Powell expanded on principles first articulated in 1984 by Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger.

Powell championed the notion that these questions should all be answered affirmatively before the United States should take military action:

- Is a vital national security interest threatened?

- Do we have a clear, attainable objective?

- Have the risks and costs been fully and frankly analyzed?

- Have all other nonviolent policy means been fully exhausted?

- Is there a plausible exit strategy to avoid endless entanglement?

- Have the consequences of our action been fully considered?

- Is the action supported by the American people?

- Do we have genuine broad international support?

After 20 years of waging a global war on terror, it should be painfully clear to any military strategist worth his salt that pursuing clear, attainable objectives and plausible exit strategies to avoid endless entanglement are in the best interests of the nation.

“With hindsight, the last two wars suggest that General Powell was not wrong in wanting a more deliberate approach to the Supreme Judgment,” National Defense University’s Frank Hoffman wrote in 2014.

Pointing to a series of successful military operations under his tenure as JCS chairman, Powell wrote in 1992, “The reason for our success is that in every instance we have carefully matched the use of military force to our political objectives. … We owe it to the men and women who go in harm’s way to make sure that their lives are not squandered for unclear purposes.”

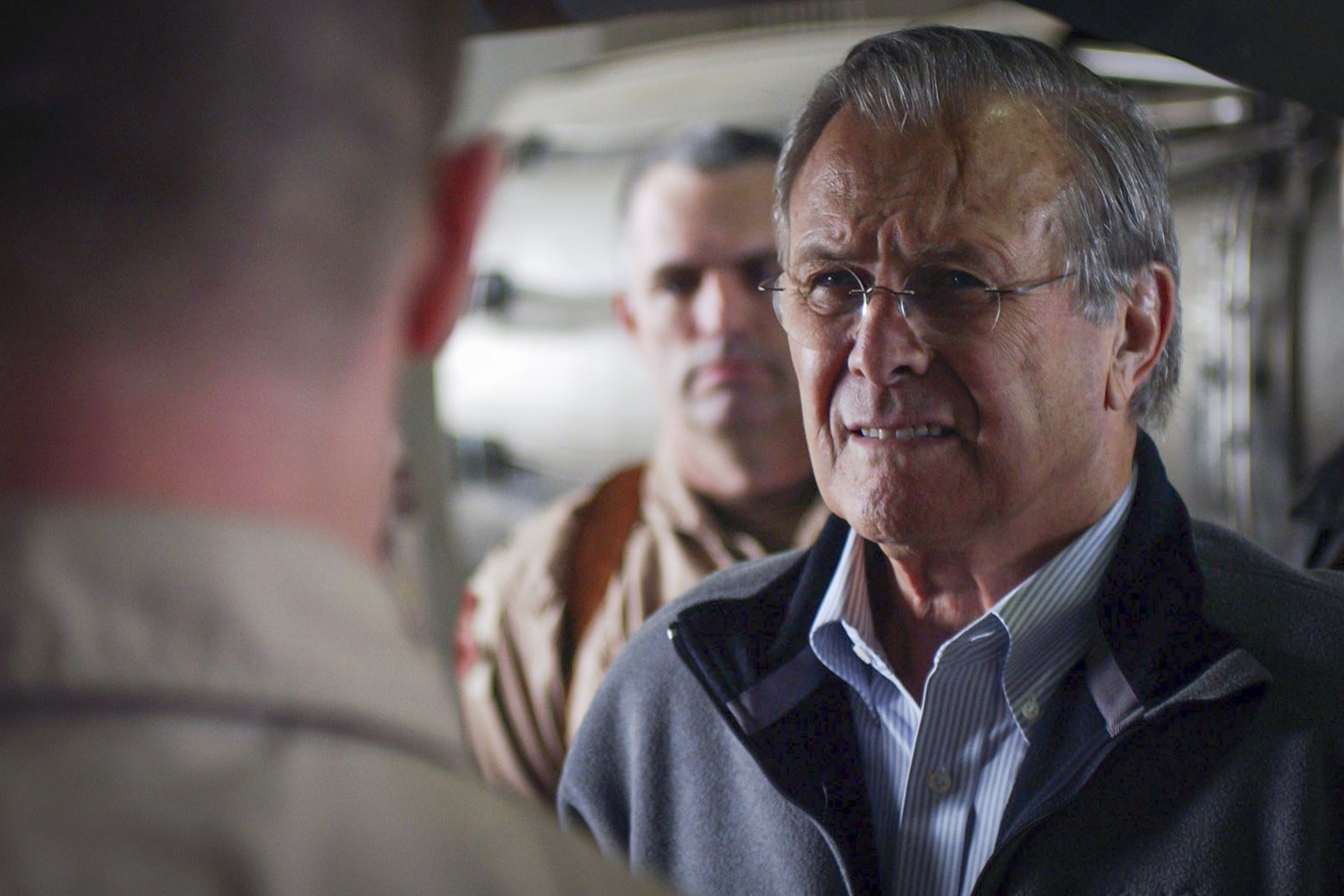

As President George W. Bush’s first defense secretary, Donald Rumsfeld ignored lessons from Korea and Vietnam and oversaw two wars defined by constantly shifting strategic objectives and a lack of any clear exit strategy.

In November 2001, with the Afghanistan war barely a month old, Bush instructed Rumsfeld to discreetly begin reviewing the Pentagon’s war plan for Iraq. Over several months and meetings with Gen. Tommy Franks, head of US Central Command, Rumsfeld pressured the general to reduce the number of troops the plan called for from 400,000 to around 150,000.

In October 2002, Bush made his case for military action against Iraq to members of the House International Relations Committee, saying, “People out there say you cannot fight in Afghanistan and win in Iraq. Defeating two enemies is very difficult, but we will do it.”

Retired Marine Lt. Gen. Greg Newbold, who resigned in 2002 from the JCS in protest of Rumsfeld’s invasion plans, later wrote that US forces were sent to Iraq “with a casualness and swagger that are the special province of those who have never had to execute these missions — or bury the results.”

In February 2003, then Army Chief of Staff Gen. Eric Shinseki testified to the Senate Armed Services Committee that a successful invasion and occupation of Iraq would require “several hundred thousand soldiers.”

“We’re talking about post-hostilities control over a piece of geography that’s fairly significant with the kinds of ethnic tensions that could lead to other problems,” Shinseki said.

Two days later, Rumsfeld and then Deputy Defense Secretary Paul Wolfowitz dismissed Shinseki’s assessment in the media. Rumsfeld said Shinseki’s numbers were “far from the mark,” and Wolfowitz used the words “wildly off the mark.”

Rumsfeld’s legacy is a generation of American warriors for whom victory proved as elusive as the moral authority with which the Iraq war was waged. History should remember Rumsfeld for the cartoon-villain levels of hubris and smug sophistry with which he helped launch us headlong into a foreign policy of continuous global war driven by nebulous notions of what victory actually looks like.

Powell, on the other hand, understood what was required to win wars, and he stood as the antidote to neoconservative chicken hawks like Rumsfeld, Dick Cheney, and Wolfowitz. One can only wonder what might have been if Powell had been defense secretary instead of Rumsfeld, or if any of the architects of war in Iraq and Afghanistan had embraced Powell’s doctrine of using decisive military force to win quickly and definitively.

“Once a decision for military action has been made, half-measures and confused objectives exact a severe price in the form of a protracted conflict which can cause needless waste of human lives and material resources, a divided nation at home, and defeat,” Powell wrote in the 1992 National Military Strategy. “Therefore, one of the essential elements of our national military strategy is the ability to rapidly assemble the forces needed to win — the concept of applying decisive force to overwhelm our adversaries and thereby terminate conflicts swiftly with a minimum loss of life.”

When the US invaded Afghanistan in the fall of 2001 with the goal of capturing or killing Usama Bin Laden and destroying al Qaeda and its surrogates, President George W. Bush opted for a strategy that minimized the number of US troops deployed. Rumsfeld’s plan relied primarily on the CIA and small teams of US Special Forces who advised and funded anti-Taliban militias such as the Northern Alliance.

By December 2001, Bin Laden and his followers were on the run and holed up in the mountain stronghold of Tora Bora in northeastern Afghanistan. As commander of the 1st Marine Expeditionary Brigade, then Brig. Gen. James Mattis had 4,000 Marines in the Afghan theater. When he requested permission from US Central Command to surround and seal off Bin Laden’s lair and finish the mission, CENTCOM Commander Gen. Tommy Franks denied the request.

“The Bush administration later concluded that the refusal of Centcom to dispatch the Marines — along with their failure to commit U.S. ground forces to Afghanistan generally — was the gravest error of the war,” Mary Anne Weaver wrote in The New York Times Magazine in 2005.

If Franks and Rumsfeld had opted to apply “decisive force to overwhelm our adversaries and thereby terminate conflicts swiftly,” Bin Laden likely would have been killed or captured and al Qaeda routed within months of the 9/11 attacks. Instead, about 800 al Qaeda fighters escaped Tora Bora, and Bin Laden left around Dec. 16, making his way over the border to Pakistan, where he stayed until he was killed by members of SEAL Team 6 almost a decade later.

Colin Powell was an American warrior, a trailblazer, one of our finest military leaders — a shining example of what we talk about when we talk about the American dream. Some will remember him as the man who closed the sale for the Iraq war. To me, he will always be the man we should have listened to about when and how to go to war. I can think of more than 7,000 reasons why Powell’s doctrine has enduring value — perhaps now more than ever.

I wonder if we can hear the general now that he’s gone.

Read Next: After Afghanistan, It’s Time To Admit Counterinsurgency Is a Losing Doctrine

Ethan E. Rocke is a contributor and former senior editor for Coffee or Die Magazine, a New York Times bestselling author, and award-winning photographer and filmmaker. He is a veteran of the US Army and Marine Corps. His work has been published in Maxim Magazine, American Legion Magazine, and many others. He is co-author of The Last Punisher: A SEAL Team THREE Sniper’s True Account of the Battle of Ramadi.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.