6 Legendary Prohibition Showdowns Between Gangsters, Lawmen, Rum Runners, & Bootleggers

Group portrait of a police department liquor squad posing outdoors with cases of confiscated alcohol and distilling equipment during Prohibition. (Photo by Archive Photos/Getty Images)

The Roaring Twenties weren’t as glamorous as they’re often portrayed in movies and on TV. The arrival of the Jazz Age on the social scene, the Harlem Renaissance that embraced artistic expression, and the boom in economic prosperity were some of the highlights of the decade. The shadier side involved high crime rates, bloody turf wars, and medical malpractice all as a direct result of a series of political decisions that launched the criminal underworld into an upheaval.

At the center of this division was the temperance movement, which called for the moderation of alcohol. Despite President Woodrow Wilson’s veto, it went forward when Congress approved the ratification of the 18th Amendment. This federal law restricted the manufacturing, distribution, and transportation of liquor. The Volstead Act (commonly known as the National Prohibition Act) passed in 1919, and it went into effect on Jan. 17, 1920.

The Prohibition Era (1920-1933) was one of the bloodiest periods in law enforcement history, and it began 100 years ago today.

The power vacuum between crime families and street gangs enthralled several major U.S. cities with widespread violence. Volatile conditions and corruption were rampant, and newspapers ran repetitive headlines of nationwide scandals. The desperate times sparked a series of epic showdowns between crime fighters and law breakers. Their bouts have come center stage — some popularized by the Hollywood spotlight, others nestled in rarely visited corners of history. The bootleggers, gangsters, Prohis (pronounced pro-hees, a nickname given to prohibition officers), chemists, owners of speakeasies, and even the average citizen were all affected in their own ways.

Bugs Moran vs. Al Capone

The city of Chicago was riddled with gangsters profiteering on bootleg whiskey rings and smaller rackets. The most notorious were the North Side Gang, run by Dean O’Banion, and their rival, the South Side Gang, commonly referred to as the Chicago Outfit, led by Al Capone. O’Banion set up Johnny Torrio, a member of the Chicago Outfit, in a police sting. Al Capone called for O’Banion’s assassination and murdered him in cold blood in a flower shop. Bugs Moran, who historians credit for popularizing the drive-by shooting, vowed his revenge.

Moran and Capone were feared and respected amongst the populace and were in the midst of a violent turf war. They devised schemes to undermine each other and routinely planned, carried out, and executed ruthless killings to seize control of power on the streets.

Moran ordered and attempted three assassinations on Al Capone and his gang — two drive-bys and one torture and execution of Capone’s bodyguard. Moran may have not killed Capone, but his tactics were so effective that Capone outfitted his 1928 Cadillac Town Sedan with custom armor plating, bulletproof glass, and submachine gun storage. The vehicle was later owned and utilized by President Franklin Roosevelt following the Pearl Harbor attacks.

On Feb. 14, 1929, The Chicago Daily News headline reported a “Massacre of 7 Moran Gang,” which was later referred to as the St. Valentine’s Massacre. Seven associates belonging to Moran’s North Side Gang were executed by four perpetrators wearing police uniforms in a garage on North Park Street in Lincoln Park. Frank Gusenberg was the only survivor of the shooting; however, he died days later from his wounds.

The Chicago police tried to question Gusenberg while he recovered from emergency surgery to fill the 14 bullet holes he had sustained. When the cops asked who shot him, he replied, “No one shot me.” The target for the shooting was Moran, but the shooters’ lookouts allegedly fingered the wrong guy. Al Capone, the fabled mobster, reached Chicago PD’s Most Wanted List. He was never arrested for this crime because he had an alibi that placed him at his home during the shooting.

The gun violence and shootouts during this era spawned the world’s first Scientific Crime Detection Laboratory to study forensic and ballistic evidence. Its creation is largely due to the post-St. Valentine’s Massacre push to “revamp the city’s image.”

The Rum Patrol vs. The Black Duck

The Coast Guard’s mission during the Prohibition Era was to conduct interdiction operations and search and seizures of illegally transported contraband on suspected vessels at sea or at coastal ports. Early on, they were undermanned, underfunded, and lacked the patrol craft to carry out their mission immediately. Over time, they secured 31 naval destroyers and “six bitters” capable of traveling 25 knots to chase down larger “rum runners” during the “Rum War.” Crime syndicates smuggled rum from San Francisco to New York to Chicago to New England and beyond, and had sophisticated tactics at ports, always wary of pirates hijacking their vessels at night.

The most famous rum runner in New England during the Prohibition Era was the “Black Duck,” a Gloucester vessel known to be able to outrun and outmaneuver any of the rescue surf boats, destroyers, and former sub chasers in the Coast Guard’s arsenal. The Black Duck’s skipper was Charlie Travers, a former U.S. Life Saving Service surfman known for his innovative mind and extraordinary seamanship. After his service, he attached a car motor to his fishing boat, which enabled him to operate a very successful business as a lobsterman.

He realized the rum trade sold more than lobsters, and after receiving a slap on the wrist in 1925 for trying to smuggle $10,000 worth of liquor, he upped his ante. At the age of 21, Travers had equipped the Black Duck with two World War I surplus V-12 Liberty aircraft engines and souped up its horsepower to reach speeds up to 32 knots. The Black Duck even had a smoke screen system and machine guns for defense.

Travers hand-selected his crew, including his partner, Max Fox, better known as Charles Soloman or “King Solomon.” He was declared “Boston’s Al Capone.” On the cold and foggy night of Dec. 29, 1929, the Coast Guard engaged in a boat chase with the Black Duck, opening fire and killing three of its crewmembers.

Two days later, Travers was wounded by a high-caliber bullet that shattered his wrist, and he was arrested. The violence of the Black Duck incident helped shift public opinion toward repealing Prohibition.

“Ginger Jake” vs. Everybody

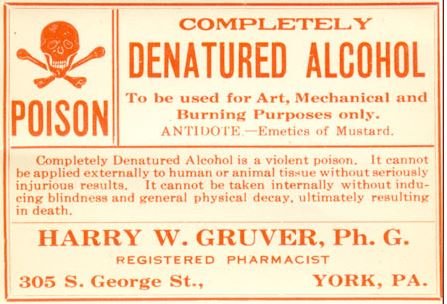

There have been times when the U.S. government miscalculated the intentions of criminals. One of those times was during Prohibition, when they ordered legal industrial alcohol to be infused with wood alcohol or other ingredients. Their intention was to make the industrial alcohol smell and taste too bad to be drinkable. What the U.S. government and the Internal Revenue Bureau did not account for was Prohibition-era gangsters stealing nearly 10 million gallons and reselling it to the general public — without removing the poisonous wood alcohol.

Drinking denatured alcohol, or foul smelling and bitter-tasting bootleg whiskey, caused tens of thousands of citizens to go blind, become seriously ill, or die. Two Boston brothers, Harry Gross and Max Reisman, in an effort to make a quick buck in 1928, had developed their own poisonous drink called “Ginger Jake.” They marketed it as “liquid medicine,” but by 1930, some 35,000 to 100,000 people had developed the “jake leg,” or a limp caused by the dangerous chemicals and additives in the alcohol.

Another interesting aspect to the Volstead Act was how pharmacies rose to power selling alcohol as medicine. Walgreens in particular went from just 20 local stores to as many as 500 as their shady business filled their pockets handsomely, despite the ethics in medical malpractice.

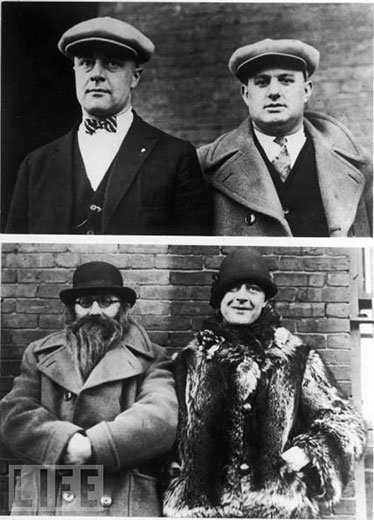

Izzy Einstein & Moe Smith vs. 5,000 Bootleggers

Chicago wasn’t the only major U.S. city that had rackets of bootleg whiskey causing a ruckus between Prohis and bootleggers. New York City had a wiseguy problem, and Isadore “Izzy” Einstein and Moe Smith weren’t initially the tag-team the city was looking for. Einstein stood 5-foot-5, had a stocky build, and didn’t look the part to mingle amongst the likes of inner-city gangsters. Smith had equal stature, a big belly, and a double chin. Together the unlikely tag-team would arrest 5,000 bootleggers by using their intellect rather than intimidation.

Einstein could speak six languages, could ad-lib like a cocksure actor, and had the ability to establish a connection with anyone. His most famed exploits led to his nickname “the man of a thousand disguises.” He dressed as a woman, a Texas oil man, an athlete who had just finished a muddy scrum, and on several occasions as a prohibition agent who the doorman thought was just a gag. Einstein invented a device to provide undeniable evidence of whiskey in the speakeasies he frequented. He used a rubber hose that connected to a small pocket in his coat jacket where a hidden flask accepted its contents. He would either arrest the barkeep right then and there, or he would go to the bathroom, write down the speakeasy’s name and address, and return with more of his “friends” at a later time.

Einstein, alongside Smith, a former cigar salesman, traveled from New York to New Orleans, Saint Louis, Atlanta, and Pittsburgh, donning disguises along the way. Hollywood heartthrobs weren’t safe from Einstein and Smith, either. The pair showed up to an audition as extras dressed in steel-plated armor for a medieval movie. When they were invited to a nearby speakeasy afterward, they arrested the actors. They also used props such as a pickle jar because, as Einstein explained, “Who’d ever think a fat man with pickles was an agent?”

Although they were eventually fired for “not living up to the standards of efficiency,” according to the newer Prohibition administration, their track record of 4,932 arrests on an estimated 5,000 bootleggers speaks for itself.

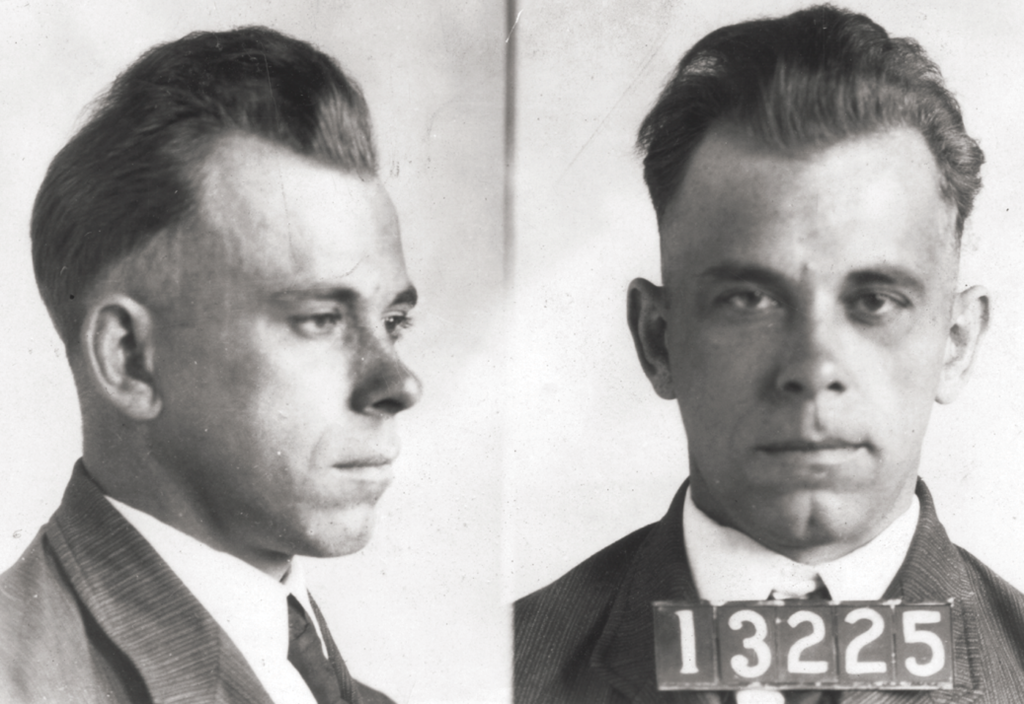

Melvin Purvis vs. Public Enemy Number One

One person isn’t usually responsible for bringing down an empire, nor are they usually responsible for capturing the most feared and reputable criminals in their career. Melvin Purvis, the man who became the youngest field office chief in the entire FBI, apprehended three in just four months. In 1930, at the age of 27, he was promoted from the Cincinnati Bureau and bounced around from Washington to Birmingham, Alabama, and eventually to Chicago, one of the most prized locations for special agents. He was soft-spoken, wore elegant suits and an expensive hat, and was a bachelor who charmed many women.

In July, October, and November of 1934, Purvis confronted three gangsters cast as “America’s Public Enemy Number One”: John Dillinger, who had committed mass murder, bank robberies, and three jail breaks; Charles “Pretty Boy Floyd,” the prime suspect of the “Kansas City Massacre” that killed four police officers; and Baby Face Nelson, a violent bank robber and gangster. Purvis, with the assistance of other officers, gunned down all three in bloody shootouts.

Miraculously, this feat has not been surpassed in nearly a century and isn’t his only fascinating career highlight. As the FBI’s “G-men” grew in fame during the ’30s, newspapers cast them as celebrities fighting against ruthless gangsters. Purvis’ reputation had a global impact, and when he traveled across the pond on a European vacation, he did so under the alias Oscar Smith. He opened the Paris World Fair and then traveled to Berlin. While staying at his hotel, his phone rang. On the other end was Hermann Göring, the German aviation hero who was ordered by Adolf Hitler to establish their secret police, the Gestapo, just two years prior to their meeting.

Göring invited Purvis to his large hunting estate northeast of Berlin. As an avid huntsman, Purvis successfully stalked wild boar with a spear, returning with tusks and a sword Göring personally gifted to him.

When the U.S. entered World War II, Purvis rose to the rank of colonel as an intelligence officer. He also worked as the Deputy Director of the War Crimes Office. Nearly a decade earlier, Purvis and Göring were hunting wild game side by side; now they were sitting across from each other in an interrogation room. By 1946, the Nuremberg Trials were in full swing, and Göring asked Purvis if there was any way he could avoid execution. Purvis calmly replied, “No.”

The Untouchables & Elmer Irey vs. Al Capone

“The Untouchables” wasn’t a nickname given in jest but for their commitment to fighting crime. While policemen and prohibition officers elsewhere were bribed, coerced to look the other way, or perpetuated other acts of corruption, Elliot Ness and his squad of loyal federal agents never wavered. They tracked bootleggers and smugglers as they traveled to and from Canada and Europe. They hunted the most feared mobsters through Chicago’s city streets. Ness never once shied away from confrontation in “the crime capital of the world,” and he gained a legendary, almost mythical reputation early on that mirrored that of nemesis Al Capone.

Although Ness and The Untouchables weren’t responsible for Al Capone’s demise, they did harass the mafia kingpin and totaled 5,000 Prohibition violations against his name. While Ness sought Capone’s stashed caches of alcohol and undisclosed breweries, Elmer Irey, who has since been dubbed by Life magazine as “one of the world’s greatest detectives,” and his T-Men (Treasury Men) worked tirelessly behind closed doors to put Chicago’s Most Wanted man behind bars.

They operated in secret and received little, if any, limelight from the tabloids at that time. Irey’s T-Men were IRS special agents who were determined to wipe the grime away from corrupt city officials, invinceable gangsters, and pesky tax evaders.

Since its inception in 1919, the IRS’s historic reputation has never fallen below its 90 percent conviction rate for federal tax persecutions. Irey’s Intelligence Unit had two premier investigators for these landmark cases: Frank Wilson and Mike Malone. Wilson one of the accountants that followed the paper trail and backend dealings of Capone’s criminal empire. He was named the head of the Secret Service in 1937. Malone, known as “Mysterious Mike” to his family and friends, worked undercover in the most dangerous assignments. He assumed aliases — one posing as an Irish mobster named Pat O’Rourke, another as Mike Lepito, a Philadelphia racketeer who lived next door to one of Capone’s bodyguards.

His high-risk undercover work and the teamwork of the Intelligence Unit helped convict Capone for tax evasion and led to the arrest of several notable criminals like Enoch “Nucky” Johnson, who inspired the fictional character Nucky Thompson in the hit HBO series “Boardwalk Empire.”

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.