Riot police clear a street with smoke bombs while clashing with demonstrators in Ferguson, Missouri, Aug. 13, 2014. Police in Ferguson fired several rounds of tear gas to disperse protesters late on Wednesday, on the fourth night of demonstrations over the fatal shooting last weekend of an unarmed black teenager Michael Brown, 18. Photo by Mario Anzuoni/REUTERS.

The first amendment of the U.S. Constitution guarantees “the right of the people peaceably to assemble,” but peaceful protests for a cause have existed in the United States since before the country had even officially formed — and violent riots have often followed after tensions overflowed. Time and time again, peaceful marches, vandalism, and tragedy have all proven to be common themes of civil unrest in America.

From the destruction of the most infamous riots to the protests in Washington that united a nation to the recent nationwide protests surrounding police brutality and gun reform — here are some examples throughout history from the 18th century to present day that shed some perspective on what it means to create change in a nation that was founded on the principles of freedom.

18th Century

The 18th century had an important mark on American history, setting the stage for the years to come. The Boston Massacre started from a street brawl between colonists and a British soldier after years of increased tensions that required the colonists to obey unfair tax laws enforced by the British. On March 5, 1770, after the ensuing scuffle, British soldiers arrived and surrounded the Customs House to prevent further unrest. The show of force increased escalations and, during the confusion, a shot rang out. The rest of the soldiers in line panicked and discharged their weapons, killing five colonists.

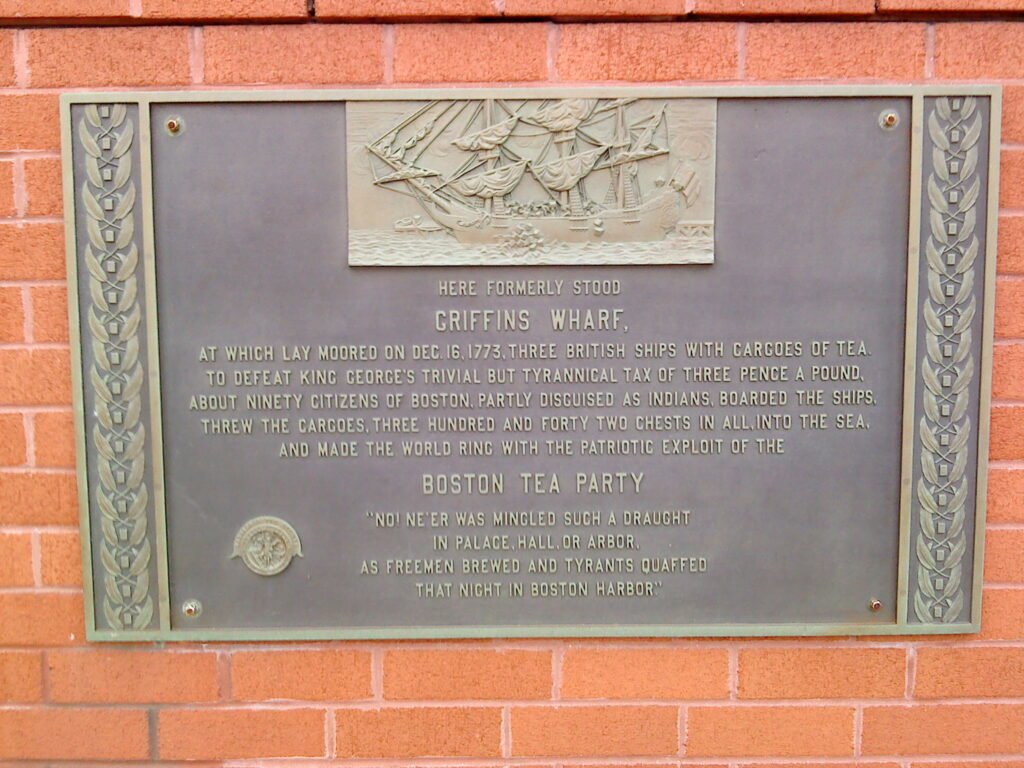

The series of events that followed the Boston Massacre provided a precedent to how modern protests are conducted to this day. In Boston, the townspeople had anti-British views and they followed the lead of the Sons of Liberty to unite together as one against tyranny. The final straw that led to action was the passing of the Tea Act in 1773, which put in motion the most prolific political protests in history. Disguised as American Indians, the liberators marched toward Griffin’s Wharf, boarded three ships, and emptied 342 boxes of British East India Company tea into the Boston Harbor. The act of defiance — famously known as the Boston Tea Party — became one of the most defining moments of the American Revolution.

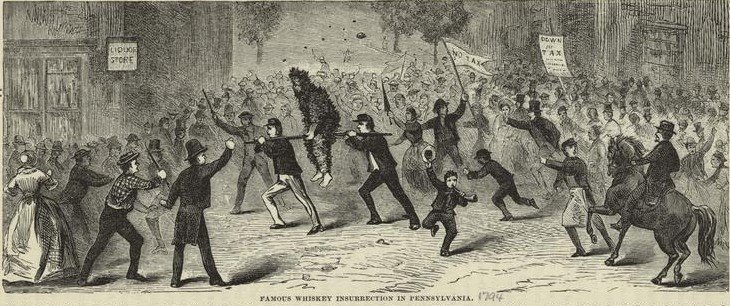

The states that participated in the American Revolution were crippled by debt. George Washington traveled from Virginia to Pennsylvania to hear the views of local governments concerning tax on whiskey. When Congress passed the bill imposing tax on a domestic product by the federal government in 1791, protests by small whiskey producers voiced their frustration as to why they were taxed 9 cents per gallon compared to the 6 cents the much larger producers were paying. The upheaval commonly known as the Whiskey Rebellion lasted for three years and was one of the first major confrontations between citizens and their recently formed federal government. A 12,950 militia force was organized by Washington to prevent further disturbances.

The Founding Fathers drafted The Bill of Rights in 1787 to guarantee individual civil liberties for the average citizen, a privilege the Constitution didn’t originally include. The first 10 amendments became the framework of the Constitution to prevent a centralized government from gaining too much power. The relevance of the Bill of Rights and ongoing protests in the 21st century always fall back to the First Amendment: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.”

19th Century

Nineteenth century protests saw the emergence of voices for women’s rights and the rise of labor strikes. The Seneca Falls Convention was a two-day assembly held from July 19 to July 20, 1848, organized by Elizabeth Candy Stanton and Lucretia Mott, who read a “Declaration of Sentiments” that modeled the Declaration of Independence with rights attributed to women. These women suffragists also joined black leaders such as Harriet Tubman to voice their support for the abolition of slavery. The counterculture movement of feminism gained some momentum, but it took nearly a century for significant progress to be made.

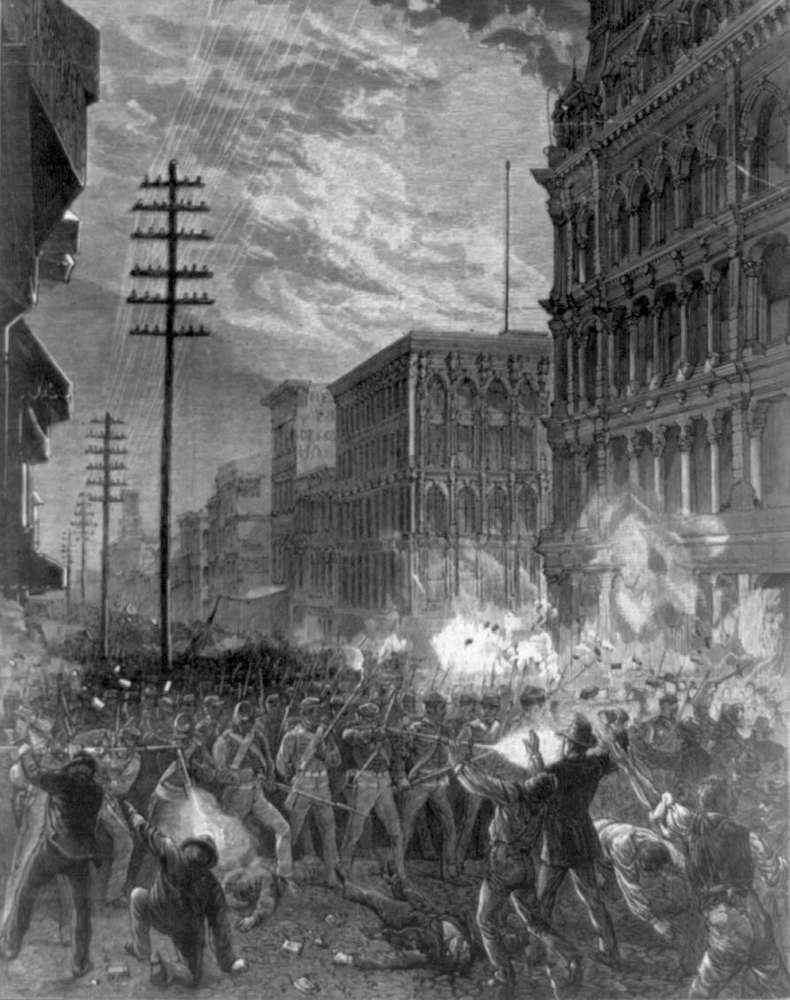

Following the American Civil War, individual liberties were still being violated on a monumental scale, resulting in race riots in Memphis and New Orleans in 1866. Clashes between white and black Americans led to 12 churches being burnt down, 81 African Americans being killed, and more than 150 people wounded during that time. The most famous labor event during the century was the “Great Railroad Strike of 1877.” In 1873, an economic depression crippled jobs, and members of the Baltimore & Ohio (B&O) Railroad suffered their second pay cut in eight months. Additionally, the railroad was dangerous work and the reduction in wages wasn’t worth the risk.

On July 16, 1877, West Virginia railroad workers refused to drive locomotives until their pay improved. The message traveled, and railroad workers from Chicago to Pittsburgh joined the strike. There were several bloody clashes between National Guard units and protestors. The protests, however, did not succeed in improving pay or bring about labor reform, despite more than 100,000 workers and nearly half of the trains in the country temporarily coming to a stop.

20th Century

The 20th century saw a noticeable increase in protest, which often turned violent. Modern-day protestors marching down a street while the National Guard stood idly by to deescalate agitators was a common scene during some of the more notable acts of expression. The protests stemmed from racial inequality, injustice, labor disputes, veterans rights, and police brutality.

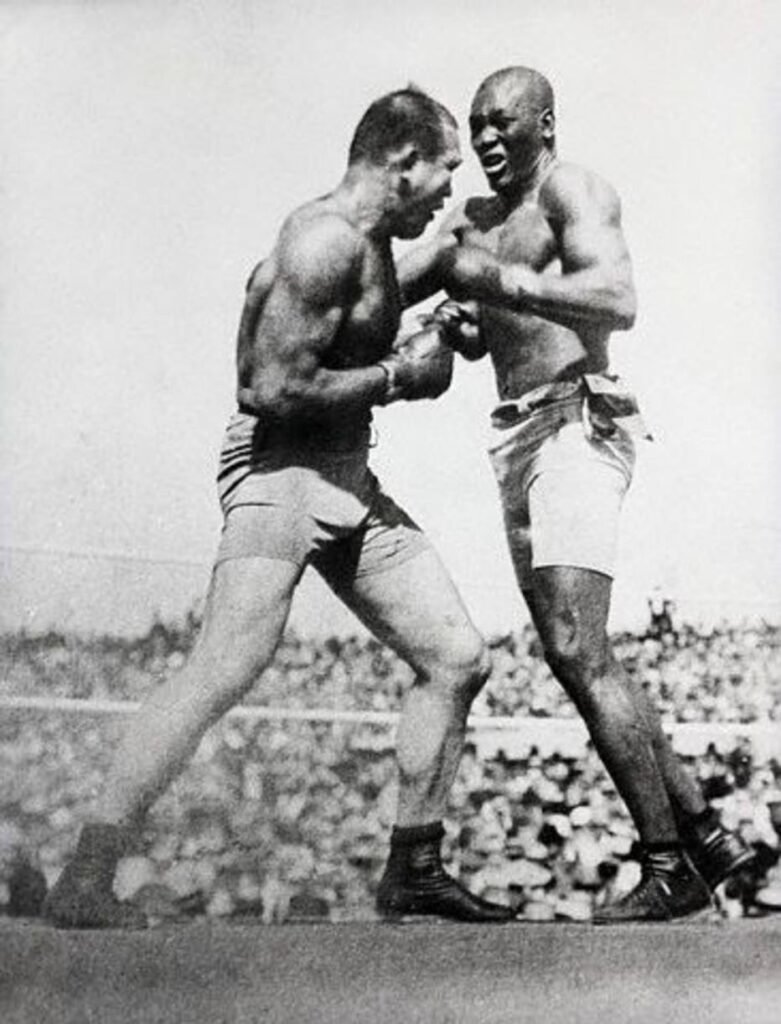

A decade into the new century, on American Independence Day, heavyweight boxers Jack Johnson and James J. Jeffries squared off in what was called the “Fight of the Century.” Johnson, who was African American, defeated Jeffries, a white man — identifying traits that are important for the events that followed. Thousands of citizens from dozens of American cities voiced their displeasure with the outcome of the fight by storming into the streets. African Americans marched block by block in support of Johnson, the first black heavyweight champion of the world, while white people protested in large part due to the pent-up frustration from the racial divide.

The white and black populations squared off in fistfights before the melee exploded into a full-fledged race riot, which continued throughout the night and into the early morning hours. From Pittsburgh to Atlanta and some Midwestern cities in-between, police quelled mobs, and miscreants on both sides were put behind bars. Congress later banned the transportation of interstate fight films to prevent the images of Jeffries’ defeat from creating civil unrest. A large gathering of people watching one of the largest sporting events in the world can sometimes result in post-championship violence, which unfortunately remains common today despite the focus being on destruction and not much else — including the sporting event.

In addition to racial indifferences, women who were still in the struggle for equal rights formed the Congressional Union of Women’s Suffrage, which launched the National Women’s Party Suffrage Campaign in 1913 to raise public awareness for the fight for a women’s right to vote. The movement that lasted nearly a century successfully pressured President Woodrow Wilson to pass the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution the day before he took office. However, it took several more years until the amendment was adopted nationwide.

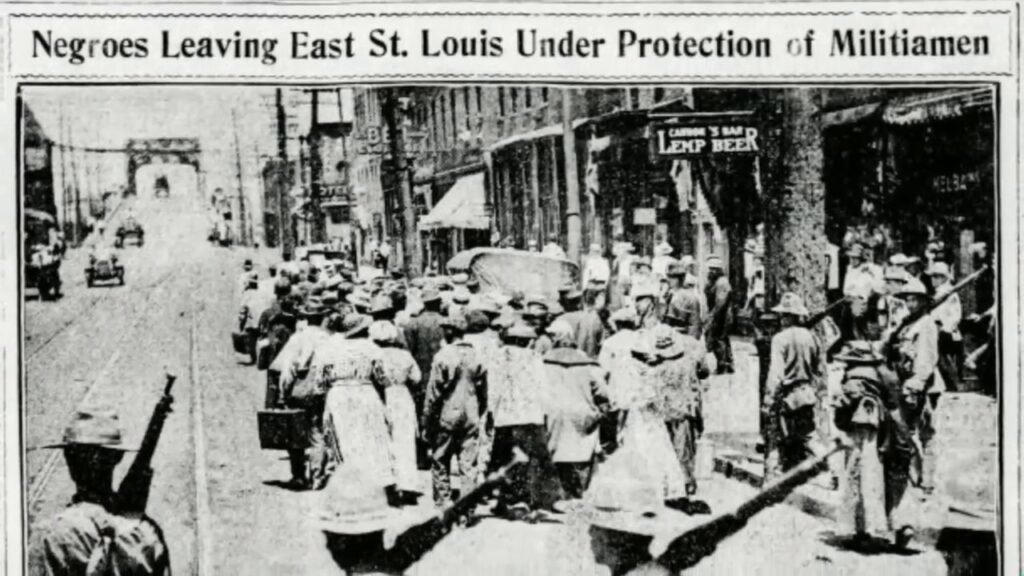

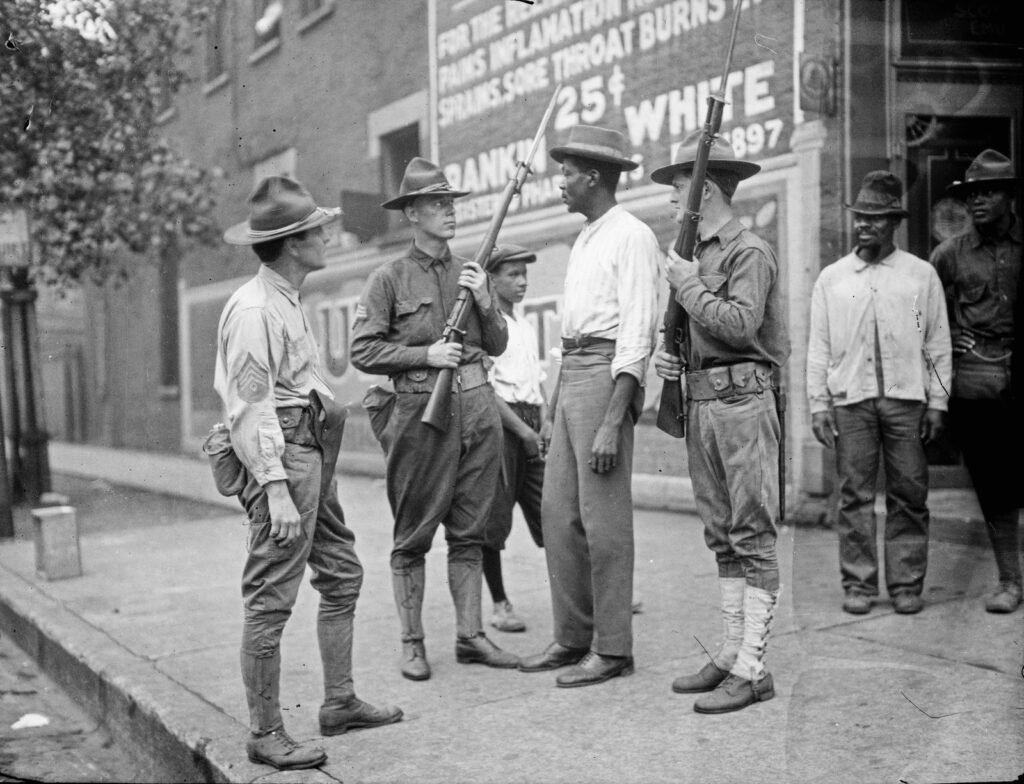

In 1917, the same year the U.S. was in the midst of “the war to end all wars,” a labor dispute in East St. Louis turned bloody. African Americans traveled north to work in factories that produced war materials. The white workers, displeased with the new workforce, went on strike. As the black population of the area surged to 6,000, a rumor spread like wildfire throughout St. Louis that a white man had been robbed by a black man. Soon, roaming gangs of white men patrolled the streets to target African-American victims. On July 1, an unknown Ford drove by an African American’s home and opened fire. In return, members of the African-American community armed themselves and fired into a Ford matching the description of the shooter’s vehicle. The two men inside were cops investigating the shooting, and they were struck and killed.

A three-day crisis resulted as mobs of angry white citizens confronted black citizens, who had few rights at that time, while law enforcement leaders did nothing to stop the violence. During the crisis, an estimated 100 African Americans were murdered. The black community had nowhere else to turn, thus a movement founded by women created the largest Black nationalist organization in the U.S to counteract white supremacy.

When African Americans returned from World War I, their heroism became yesterday’s news and white Americans fell into old habits. Some 500,000 to 1 million African Americans migrated north from the south and picked up new jobs. The mindset of the black community had changed with a newfound confidence having just returned from a war to fight for rights and end segregation. W.E.B. Du Bois famously called upon black veterans who had served in the war to not just “return from fighting” but to “return fighting” — a move white neighborhoods didn’t agree with. White veterans attacked their black counterparts, sometimes by lynching.

The violence continued into 1919, whose warmer months became know as “Red Summer,” a name accredited to bloody race riots against the black community without intervention from the government. One particularly ruthless event that culminated with reform occurred during September in Elaine, Arkansas. Governor Charles Brough instructed 500 soldiers to arrest and “shoot to kill any negro who refused to surrender immediately.” An estimated 200 sharecroppers were murdered by their own countrymen sworn to protect them. The Supreme Court presided over a landmark case that argued all persons have the right to due process as opposed to barbaric mob justice.

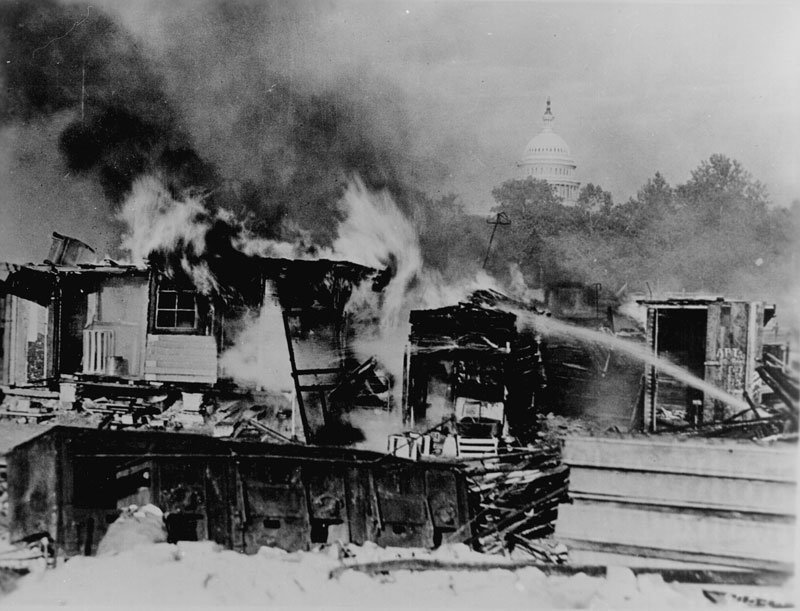

As African American soldiers returned from World War I with little rights, a bonus was granted to veterans in 1924 that was to last until 1945. However, in 1929, the Great Depression hit and the bonus became referred to as the “Tombstone Bonus” because, as the veterans said, many of them would be buried and in a grave by the time the bonus reached their pockets. World War I veterans, known as “The Bonus Army,” hitchhiked and boarded freight trains to travel across the country to march on the Capitol on June 1, 1932. An estimated 1,500 men, some who brought their families along, protested for months, often camping out in shanty towns that supported their cause.

In just two weeks, their cries for assistance were heard and a bill of $75,000 was passed through the House of Representatives. However, the bill was rejected by the Senate. More World War I veterans arrived, numbering 10,000 to 20,000. The Hoover administration instructed General Douglas MacArthur and General George Patton to bring 800 troops to Washington to move out the peaceful protestors. The removal caused newspapers and citizens to take sides, but ultimately, in 1936, the World War I veterans received their Tombstone Bonuses. The protests that required years to grant benefits to military service members inspired Congress to pass the GI Bill in 1944, amidst another war, to assist veterans in their pursuits of education once they left military service.

The most notable civil rights movements in America’s history came during the 1950s and ’60s. Rosa Parks refused to give up her bus seat for a white person on Dec. 1, 1955, which was followed by police being called for her arrest. For over a year, civil rights activists encouraged some 40,000 African American bus riders to avoid giving the bus company business. The protest, commonly referred to as the Montgomery Bus Boycott, introduced the world to their official spokesman, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who motivated thousands — as well as future generations — to fight for equality.

One such protest was the march on Washington, where more than 200,000 attendees demonstrated for federal civil rights laws. King gave his historic “I Have A Dream” speech on Aug. 28, 1963, calling for civil and economic rights to end racism. A leader of nonviolent racial change, King once famously said, “A riot is the voice of the unheard.” President John F. Kennedy and FBI director J. Edgar Hoover had prepared for the worst-case scenario at the nation’s capital, even going so far as to wiretap King to listen in on any plans of rioting. They also prepared a force of 4,000 National Guardsmen on the scene, with 15,000 paratroopers on standby in North Carolina. However, the message was delivered without any violence, which later helped bring the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act to fruition.

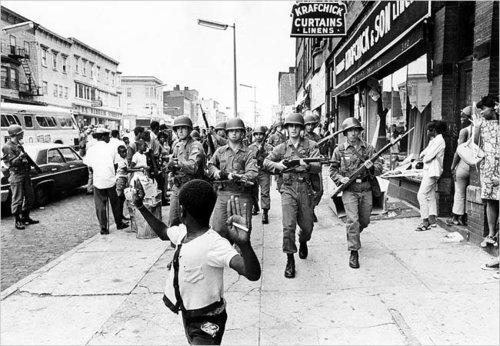

Although progress was made in the courts, tensions were on the brink of chaos within any increase of aggression. The Long Hot Summer of 1967 saw 159 race riots as African Americans were still discontent about lack of employment opportunities and segregation. In Detroit, two black service members had just returned from the Vietnam War and were celebrating inside the Blind Pig, located near the corner of 12th Street and Clairmont. Their Saturday night celebrations continued well into Sunday morning, when calls of “Police!” were heard from outside.

All 82 people were arrested as residents of the neighborhood came outside to see the commotion. As the partiers were being loaded into the back of police wagons, a mob of 200 arrived as many families were preparing for Sunday Mass. Police reported “professional instigators” in the mix of the mob. The mob turned into a riot, hurling bottles, bricks, rocks, and molotov cocktails through the windows of the businesses along the street. While the police formed a line to control the rioting, businesses were ransacked of their goods. The National Guard arrived and helped the police secure a 100-block perimeter around Virginia Park. Firefighters who responded to put out the flames had their hoses cut and received sporadic gunfire.

The unrest continued for days, and the National Guard and paratroopers from the 82nd Airborne Division had at one point used armored trucks and tanks to patrol the streets. The aftermath saw 7,200 arrests, 43 deaths, 1,700 stores looted, 1,400 buildings burned, an estimated $50 million in damage, and several families ending up homeless.

While clashes over race were increasingly relevant during the 1960s and ’70s, protests of the Vietnam War were taken up by all races. Over 100,000 protesters gathered at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington and marched toward the Pentagon on Oct. 21, 1967.

Earlier that year, King had called the Vietnam War, “a blasphemy against all America stands for.” Tragically, the youngest recipient of the Nobel Prize was assassinated on Aug. 4, 1968, on the balcony of a hotel in Memphis, Tennessee. Once the news reached households across America, hundreds of citizens took to the streets with anger in their hearts. Businesses were looted or vandalized as King’s assassination emboldened others to temporarily dismiss nonviolent protests, the message he long preached, as they believed it would not create change.

Students also participated in protests of their own, including across college campuses. The situation in 1970 that became known as the Kent State Massacre caused leaders from all civil services to reexamine how they handled civil unrest in the future, from deescalation tactics to non-lethal forms of restraints.

In Los Angeles in 1991, the police were in a high-speed pursuit chasing after a man the world would later learn was Rodney King. King had been on parole for robbery and was suspected of driving under the influence. A bystander video-taped the vicious beating of King by four police officers as he laid sprawled out on the ground. The following year, when all four officers were acquitted in court of any wrongdoing, despite the video evidence, all hell broke loose in LA.

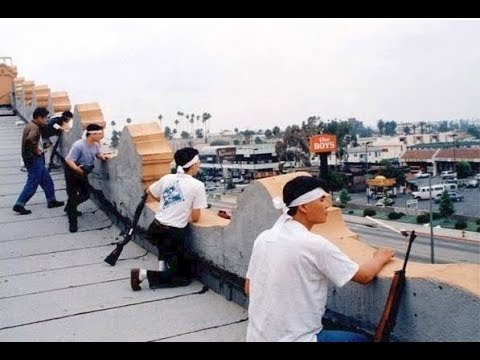

Within hours of the verdict being delivered, the city was burning — and continued to burn for six days. Stories such as Korean business owners arming themselves and taking to the rooftops to prevent looters to the brutal assault of truck driver Reginald Denny are two memorable instances of the out-of-control nature of the unrest. An estimated 2,000 Korean-owned businesses were damaged during the event called Sa-I-Gu, or April 29, in reference to the date their lives were changed forever.

The U.S. military, federal law enforcement, the National Guard, and state and local police agencies deployed; by the riot’s conclusion, 63 people had been killed, some 2,000 people were injured, more than 12,000 others were arrested, and $1 billion worth of property was destroyed. A retrial was set for the four police officers who were initially acquitted. Two were later found guilty of violating King’s civil rights.

21st Century

Just two decades into the 21st century, we have already seen our share of protests and riots due to racial and economic inequality. Many American citizens have marched in city streets, raised their cardboard signs, and vocalized their cries for justice.

In 2003, the U.S. military invaded Iraq, just two years after the invasion of Afghanistan. The long debate of whether the U.S. military should or should not have invaded Iraq can be scrutinized more heavily today now that more facts are available. However, on Feb. 15, 2003, between 6 million and 11 million people from 650 cities around the world and in major cities across the U.S. protested the invasion of Iraq, making it the single-largest one-day anti-war protest in history.

While Americans supported the invasion of Afghanistan in response to the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, protestors questioned whether the invasion of Iraq was necessary despite the government’s claim that they possessed weapons of mass destruction. The protests and numerous arguments against the U.S. government’s decisions fell on deaf ears as their efforts were ignored.

The Occupy Wall Street movement took the nation by storm in 2011 when protesters across 100 American cities and 1,500 cities worldwide protested how banks, large corporations, and the stock market were responsible for the largest economic recession in recent memory. The protest put social and economic inequality under a microscope, as well as highlighting how corporations influenced policymaking. The rallying cry “We are the 99%” vocalized the median income of Americans from differing economic backgrounds and how each was in the fight against the “1 percenters.” The Occupy Wall Street movement also brought the conversation of student debt into focus, which remains a talking point to this day.

Over the course of the 2010s, protests highlighted calls for gun reform and police reform in response to several school shootings and police brutality events. On Aug. 9, 2014, Ferguson, Missouri, police officer Darren Wilson shot and killed Michael Brown, an unarmed black male who had just robbed a local convenience store and had possibly attempted to reach for the officer’s gun. In the wake of Brown’s killing, protests called for Wilson to be fired and imprisoned. This event became the foundation of the Black Lives Matter movement, who organized protests in the streets. BLM gained support from professional athletes and celebrities who voiced the need to reduce police brutality against the black community.

In the summer of 2016, a small group of protesters gathered in North Dakota on the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation to unite against proposed plans for the Dakota Access Pipeline. By December, protesters who united around the #NoDAPL movement caused the protest camp to swell to nearly 25,000 people. Although the protest was largely peaceful, there were multiple instances of police, protesters, and private security contractors facing off amidst a slew of less-lethal munitions. A particularly brutal North Dakota winter storm caused many protesters to eventually depart the camp that had formed along Highway 1806. On February 23, the camp was cleared by SWAT officers moving from teepee to teepee, until all of remaining protesters had either evacuated or been arrested.

For years, police shootings against African Americans that resulted in the police officer being acquitted after trial further deepened the divide between the police and the black community. The growing frustration among the African American community came to a head in the city of Ferguson, where 19 days of civil unrest brought forth questions about how to better enforce a crackdown against police brutality. Further conversations concerning riot control and the militarization of police were brought to the attention of state government officials.

During these conversations, another critical problem in America was unfolding. The most violent year of school shootings in history occurred in 2018, averaging one school shooting every eight school days. The frequency of shootings in schools targeting children — with the shooters often being students themselves — reached an apex when 17 people were killed at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida.

A month after the shooting, more than 3,000 students from Stoneman marched to their football field for a moment of silence for the victims. Their attention then turned to Washington, and with the support from Democratic lawmakers, they focused on gun control legislation in hopes to reduce school shootings in the future. Their efforts, though noteworthy, remain static, until the next school shooting brings the spotlight back onto the conversation.

In 2020, which already brought with it a global coronavirus pandemic, the most gripping news story has been the civil unrest occurring around the nation in response to the excessive-force killing of George Floyd on May 25 in Minneapolis. While the killing of Brown and other African Americans by the hands of police furthered conversations of excessive force, the video of former officer Derek Chauvin kneeling on Floyd’s neck has captivated and enraged the nation.

The mass protests in every major city in the country, while still in the midst of a pandemic, were just the beginning. Increased violence has been traced to outside instigators like ANTIFA, senseless killings of law enforcement officers has proliferated around the country, and the Minneapolis City Council recently voted to defund the police department — all unprecedented events with effects that could possibly change the course of American history.

In lockstep with the founding fathers, American citizens have been inspired to rise up, face uncertainty, and inspire a generation of leaders to unite a nation founded on the resistance of injustices.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.