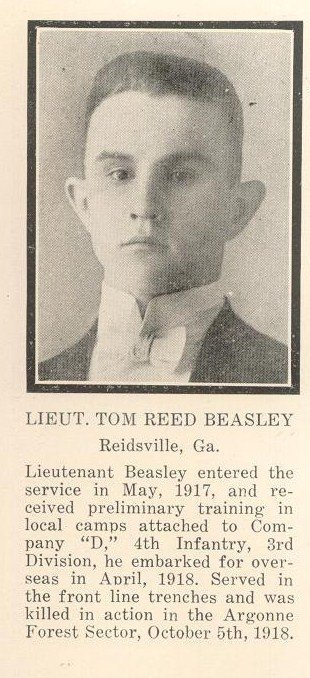

First Lt. Tom Beasley received a long-delayed Purple Heart Monday, Aug. 9, 2021, 103 years after his death in World War I. His family fought for the award for years. Images from Beasley family, Wikipedia, US National Archive. Composite by Matt White/Coffee or Die Magazine.

When 1st Lt. Thomas R. Beasley died of his wounds in October 1918, only a nurse was there to record his final words. But she sent a letter home to his family.

He’d complained, she said, of a scratch on his neck.

He never mentioned the 60 machine gun bullets riddling his torso.

A native of Reidsville, Georgia, Beasley served with Army’s 3rd Division in France, the unit that would emerge from the war with the nickname “The Rock of the Marne” for their defensive stand on the French river, a decisive moment in the closing act of World War I.

The letter from Beasley’s nurse, and a long string of letters he sent home before he died, would be the only proof of his service for his wife, his parents, and his unborn child.

Though Beasley’s wife received a telegram informing her of his death, the information was never documented in military records. As a result Beasley — like thousands of others who fought in World War I — was never put in for a Purple Heart and a century passed without his name being added to the Purple Heart Hall of Honor.

The Hall of Honor has records for only 849 men dating to the Meuse-Argonne campaign that ended WWI, a fraction of the total casualties from what was, by the time it ended on Nov. 11, 1918, the deadliest campaign the US military had ever fought. Over 1 million American soldiers participated in the Meuse-Argonne offensive and its related battles, a campaign for which the National Archives counts roughly 26,000 soldiers killed in action and another 95,000 wounded.

Beasley’s family — long after those who had ever met him had passed away — knew they were the descendants of a soldier who’d met the requirements for a Purple Heart based on the nurse’s telegram describing his fatal battle wounds. They knew through his letters exactly where he had fought and ultimately fallen.

“It was obvious because he had died,” said Beasley’s granddaughter, Kay Beasley Toups. “Things were such a wreck in Europe. For my family to have saved every letter, everything they had for 100 years and not to have the medal was pretty mind-blowing.”

The Army has to have proof and documentation of a soldier’s records before it will issue an award or any kind of merit, said Troy “Gil” Gilleland, a retired US Army colonel who works with veterans through a local nonprofit he founded.

“It quickly became a labor of love for [my wife] and me,” Gilleland said. “Our passion after retiring from the military is to help veterans and help veterans’ families. This family is the epitome of the patriotic family.”

According to the National Personnel Records Center, military records for those who were discharged prior to 1960 are considered archival and open to the public. But as Gilleland began looking into Beasley’s case, he found a gap in the records system: records kept in St. Louis, Missouri, cover only soldiers who returned from the battlefields of World War I, not those who died and were buried in France.

As a company commander in France, Beasley led charges from trenches in the fiercely contested Argonne Forest sector and was killed just over a month before the end of the war. He was interred in the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery in France.

Beasley left behind a wife with a baby on the way. The two of them would be the ones who saved his records and letters.

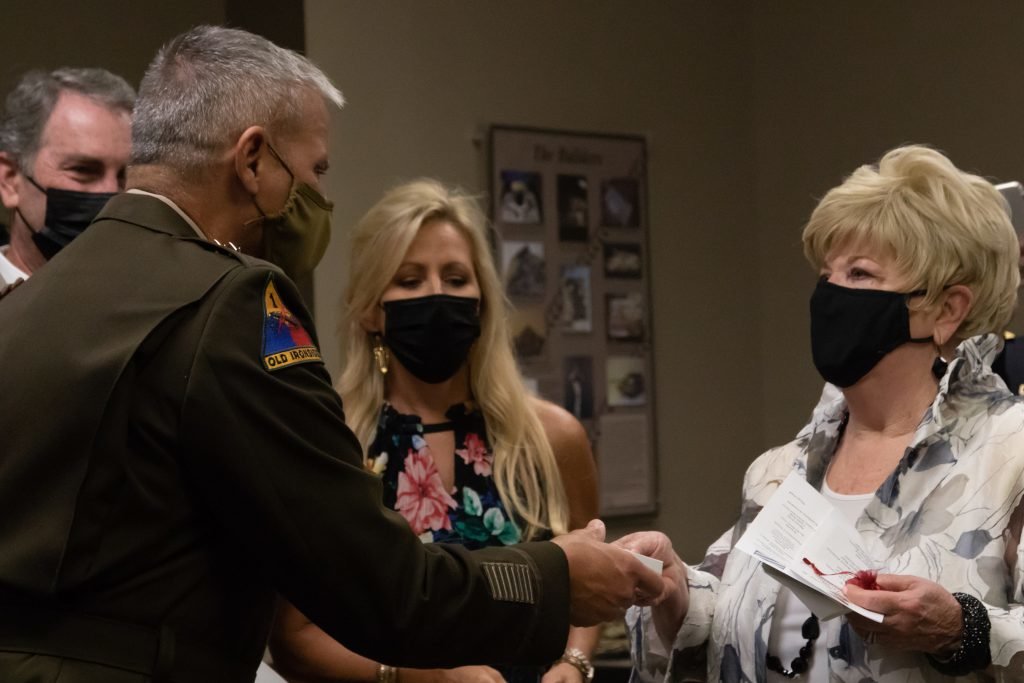

On Monday, Aug. 9, several of Tom Beasley’s grandchildren, including Kay Beasley Toups, and other extended family gathered at the 3rd Infantry Division Museum on Fort Stewart, Georgia, for a ceremony to receive their grandfather’s long-delayed Purple Heart. One hundred and three years after his death, Beasley was awarded with the Purple Heart and the Victory Medal, as presented to his family.

Maj. Gen. Charles Costanza, commanding general of the 3rd Infantry Division, presided over the ceremony and pointed at his own uniform, to the French Fourragere that members of the division wear. “This is where the division actually earned it,” he told Beasley’s family. While other Allied divisions melted away and retreated back to Paris, the 3rd Division stayed and fought, he said. “Tom Beasley was part of the reason that the division earned its nickname: ‘Rock of the Marne,’” Costanza said.

“You’ve heard about Tom sort of from a distant place,” said Roland Toups, who has been married to Kay for 57 years. “When you really think about Tom Beasley, nobody in this room actually knew or talked to Tom Reed Beasley. We are honoring a man that nobody, not even Kay, knew firsthand. That’s quite a thought.”

Costanza presented the medals and reflected on the long-awaited event.

“I never thought in my 30-year career that I’d be part of something so special,” Costanza said. “To honor a soldier, even 103 years late, means so much not just to the family, but to the Marne Division as well.”

Read Next: J.R.R. Tolkien Started Building His Lord of the Rings Universe as a Soldier in WWI

Noelle is a former staff writer for Coffee or Die through a fellowship from Military Veterans in Journalism. She has a bachelor’s degree in journalism and interned with the US Army Cadet Command. Noelle also worked as a civilian journalist covering several units, including the 75th Ranger Regiment on Fort Benning, before she joined the military as a public affairs specialist.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.