A Recon Marine Claims Self-Defense After Strip Club Murder, Has One Last Chance to Prove Innocence

Photo courtesy of John Knospler Jr./Facebook.

Too many drinks and a Wyoming snowstorm will make anyone reconsider driving home from the strip club. It was just after midnight when John Knospler Jr. was jolted awake in the driver’s seat by what sounded like someone trying to get into his car. The former Recon Marine-turned-MARSOC operator and Iraq War veteran reacted to the threat by turning the car on and attempting to get out of dodge.

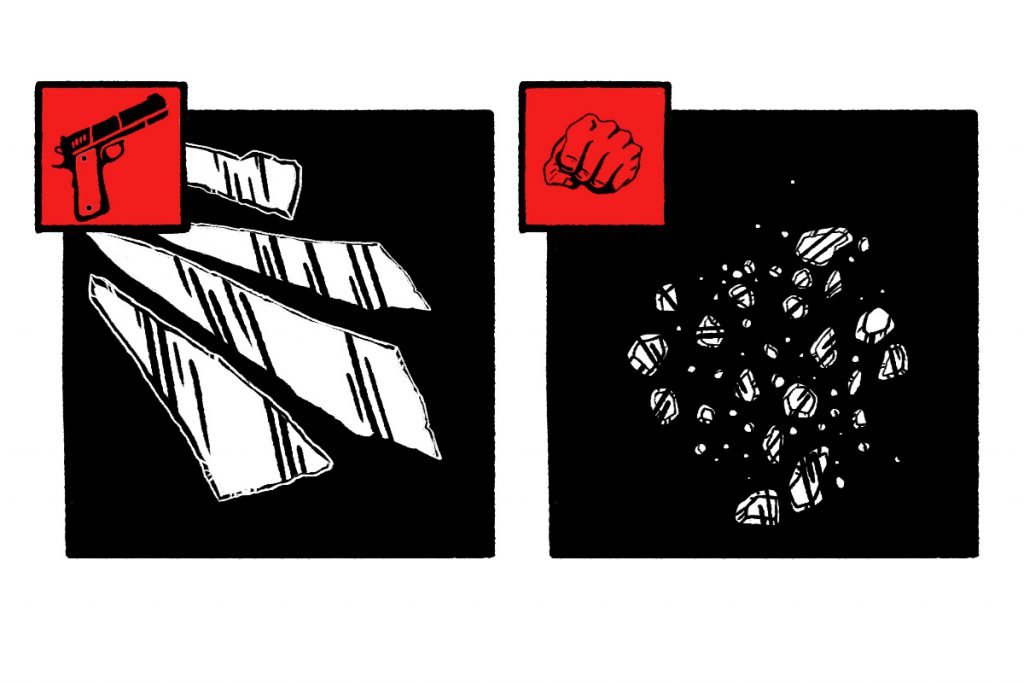

But the snow was too slick, and the tires couldn’t grip the surface of the strip club parking lot enough to drive forward. Seven feet later, he slid to a stop. That’s when his window shattered as the assailant tried to punch his way in. Knospler drew his pistol. The attacker grabbed it. The report of the pistol echoed through the cold night air, and a single round of .45 ACP impacted flesh.

The attacker stumbled back and collapsed, where he would eventually bleed out. His maroon blood stained the fresh white snow by the time EMS arrived.

That’s what Knospler says happened, anyway. Prosecutors disagreed, and a jury convicted him in the second-degree murder of 24-year-old unarmed local James “Kade” Baldwin. Knospler is now serving up to 50 years in a medium-security Wyoming prison, and his last chance to argue for his freedom is only days away.

No one disputes that Knospler shot and killed Baldwin in the parking lot of Racks Gentlemen’s Club on Oct. 4, 2013. But Knospler and his supporters think it was a legitimate act of self-defense. They also argue that an aggressive prosecutor may have presented false evidence, and their first defense lawyer asked the wrong questions.

A preliminary hearing scheduled for Aug. 11 in Casper will consider these new allegations and determine whether a new trial may proceed later this year.

“I was attacked by a violent felon who threatened my life,” Knospler says from prison. “That’s at the heart of the case. Everything you hear before and after is an attempt to villainize me.”

Knospler grew up in East Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania.

“He was very, very active,” says his mother, Patricia Christensen. “He played Little League, Pop Warner football. Very social, very intelligent. He did really well in school.”

But he didn’t always like school. He also had a tendency to challenge authority. At 13, he got in trouble for stealing from a Chinese restaurant with a group of friends. After high school, he gave college a try but dropped out after a semester and worked odd jobs laying tile and doing construction. He surprised his mother when he told her he had joined the military.

“I said, ‘Are you kidding me?’” Christensen says. “I knew his brother had always wanted to be a Marine, but John had never spoken about it at all.”

Knospler enlisted in the Marine Corps in 2000, contributing to a family tradition of military service. His father served in the Navy, and his brother would enlist in the Marines a year later — and would suffer a life-threatening grenade injury during the second battle of Fallujah.

Knospler started his career as an accounting clerk before volunteering for and passing selection as a Reconnaissance Marine after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks. He was assigned to First Recon Battalion, where he served with his friend Stephen Mull.

“John is an impeccable human being,” says Mull, who still speaks to Knospler every week in prison. “He spent eight years in Recon — you won’t find a Recon Marine who speaks ill of him.”

Knospler deployed to Iraq in 2003 and then prepared to process out of the Marine Corps stateside. He had been home less than two weeks when his old team leader, Vincent Marzi, called. They’d taken heavy casualties in Anbar Province, and Marzi was tasked with rounding up some battle-tested talent for the response.

“We’re leaving in eight to 12 days,” Marzi told Knospler. “Are you in?”

Almost 20 years later, Marzi is still impressed by the speed and timing of Knospler’s response.

“There was no hesitation,” Marzi says. “He was like, ‘I’m in. Let’s go.’”

Knospler otherwise would have been out of the Marines in a matter of weeks.

“He put his whole life on hold to support his unit. That struck a chord with me.”

Knospler served three combat deployments with Recon, then was assigned to Marine Corps Special Operations Command (MARSOC) as an instructor in the special missions training branch. He was honorably discharged from the Marines after eight years of service, then went to work for the State Department and as a private contractor in the Congo, Sudan, and Somalia.

“He was doing logistics and training military tactics,” says his girlfriend, Nhiza Fre, who has known him since 2007. “How to swim. How to patrol on the river.”

In Somalia, Knospler was beaten by a gang of thieves shortly before rotating home in 2012. He had a severe arm break that required surgery and irreparably damaged his shoulder. Doctors told him that if he got into any sort of physical altercation, he could permanently lose function of his arm. After he returned stateside, he focused on rehabilitation and spending time with Fre and family.

In October 2013, he drove his mother’s Chevrolet Cobalt to Wyoming for a hunting trip. His life would never be the same.

Knospler was not an enthusiastic hunter like his father, but the two men decided to meet in rural Keeline, Wyoming, for a family trip. After his five-year stint contracting in Africa, Knospler looked forward to a little family bonding. He also wanted to use the trip as an opportunity to vacation with his girlfriend, Fre, who was going to join him a few days after the hunt.

“We planned to go on a road trip,” she remembers. “He wanted to show me Devil’s Tower.”

The hunting trip soured. Knospler and his father, John Sr., argued. On the morning of Oct. 3, Knospler decided to get back in the Chevy Cobalt and drive an hour and a half to the nearby city of Casper.

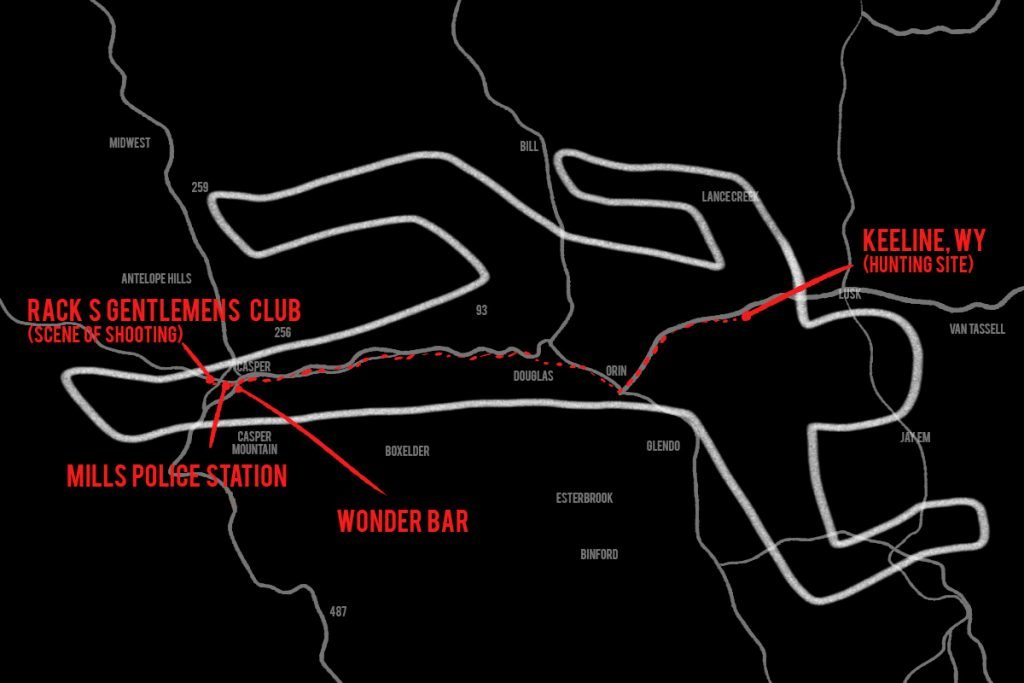

According to the timeline reconstructed during the trial, Knospler stopped at a playground in Casper for a quick workout after seeing that it had a pull-up bar. He went to a thrift store and left without buying anything. He had a steak for lunch before going to the nearby Wonder Bar for a drink. He asked the bartender where else he could kill some time, and the bartender suggested Racks Gentlemen’s Club. Security footage shows Knospler arriving at the strip club at 5:20 p.m.

Over the next three hours, he drank beer and took shots of Jameson. He occasionally went outside to smoke and check on a progressively worsening snowstorm. He chatted a bit with dancers. But mainly, Knospler sat with his phone and texted with Fre.

At 8:30 p.m., James “Kade” Baldwin arrived at Racks. Baldwin was a cancer survivor and planned to celebrate his 24th birthday with drinks and lap dances.

According to Knospler’s account, he only interacted with Baldwin once during his time inside the club. The two met in the men’s room. When Knospler found out it was Baldwin’s birthday, he took him outside to smoke marijuana. Security footage shows the two walking together to the parking lot at 9:40 p.m.

Knospler’s behavior and general disposition that evening at Racks is disputed. Security footage shows him leaving at 10:10 p.m. followed by a bouncer, Ervin Andujar, who testified in court that Knospler was asked to leave after dropping a marijuana cigarette on the barroom floor. A second bouncer, Westy Guill, also testified that on leaving Knospler asked where he could get cocaine.

Knospler adamantly disputes this version of events and says he left of his own volition, deciding to sleep in his car as he was admittedly intoxicated. A storm had moved in, leaving several inches of snow carpeting the parking lot and his Cobalt. Fre had been texting Knospler throughout the evening and says she encouraged him to sleep in his vehicle. They had planned a road trip, after all, and the trunk had been stocked with blankets and pillows for their tour of the West.

At midnight, Baldwin’s friends Chris Syverson and Kara Sterner left in Baldwin’s brother’s car, a blue Ford Fusion. Syverson said he would come back to pick up Baldwin after dropping off Sterner. Baldwin, intoxicated, passed out at his table, and the bouncers asked him to leave. They offered to call a cab, but Baldwin said his friend was waiting outside. According to the security footage, Baldwin walked out the door at 12:15 a.m., across the parking lot, and up to Knospler’s car.

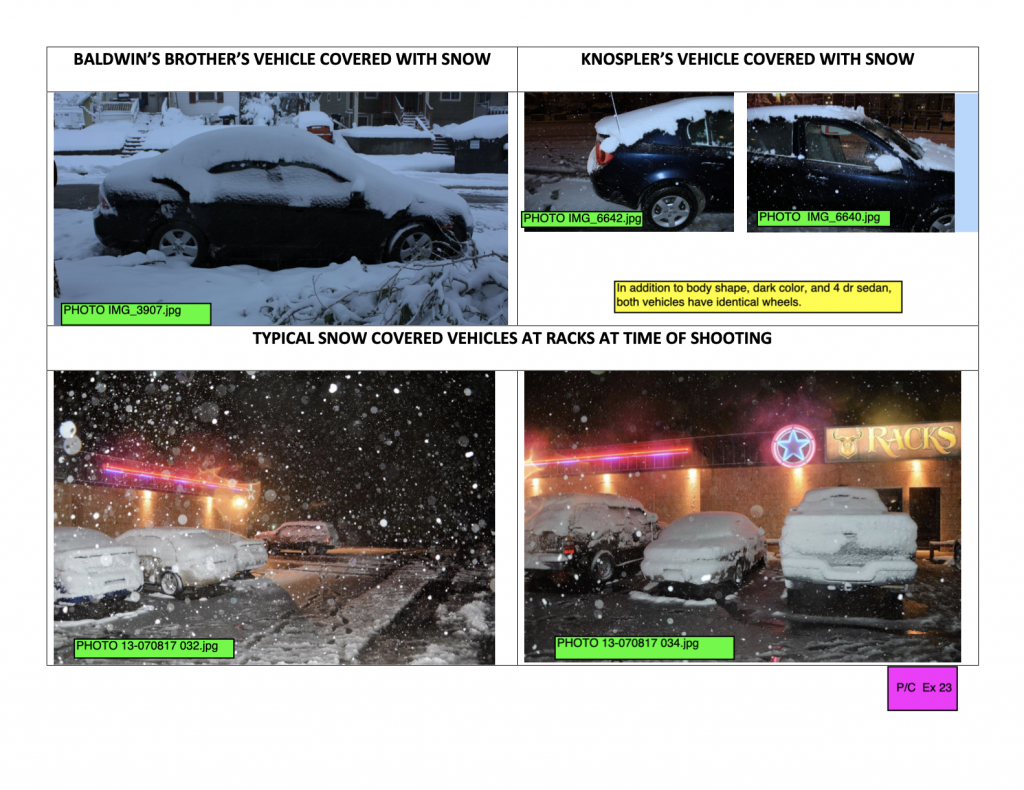

Why Baldwin approached Knospler’s car is unknown. One theory is that Knospler’s Chevy Cobalt with Pennsylvania plates — covered in 2 inches of snow — may have looked similar to the Ford Fusion that Baldwin was expecting.

According to all accounts, Baldwin went to the passenger side first and knocked on the window. By Knospler’s telling, he woke up when Baldwin knocked. Knospler started his car, at which point Baldwin moved to the front of the car, preventing him from driving away. Baldwin moved to the driver’s-side door and tried the handle. Clear to pull away, Knospler accelerated, and the car moved 7 feet forward, according to crime scene analysis, then stopped as the tires lost traction in the snow.

At trial, the prosecutor, District Attorney Mike Blonigan, alleged that Knospler shot Baldwin with a Nighthawk 1911 .45 ACP from inside the car, the single bullet breaking the driver’s-side window and killing Baldwin.

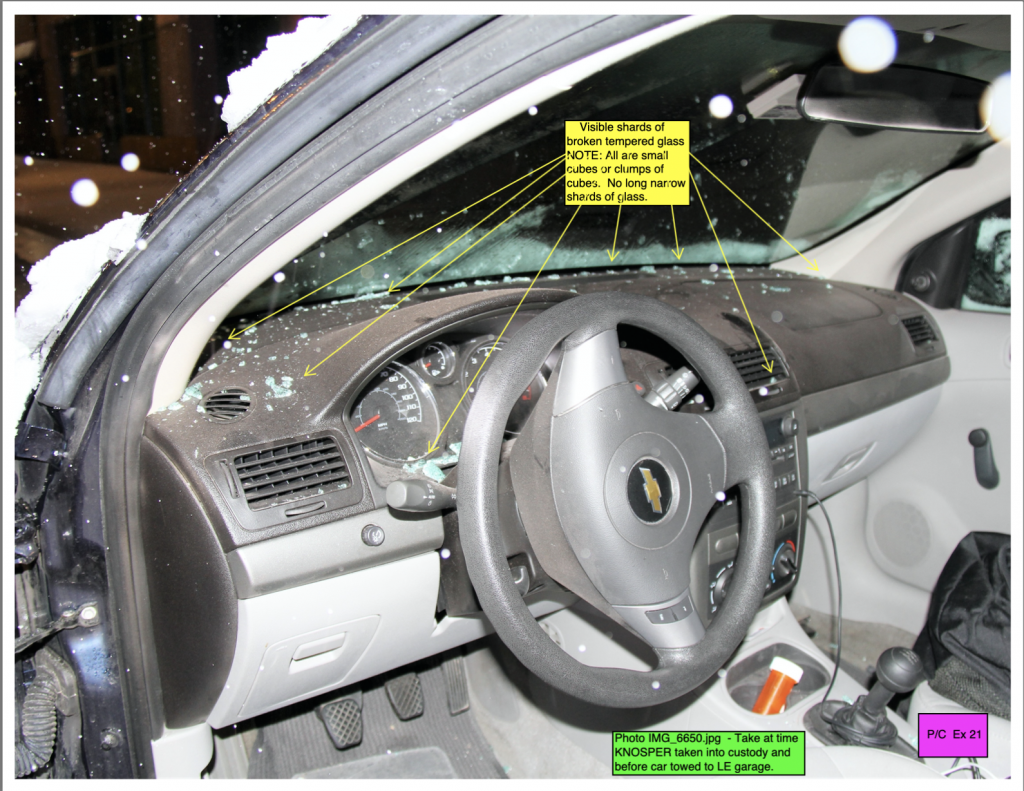

Knospler and some of the forensic evidence not included in the trial suggest a different scenario: that Baldwin smashed the driver’s-side window with his bare hand, then reached in the vehicle and attempted to grab the pistol. Only then did Knospler shoot before fleeing the scene.

Natrona County Sheriff’s Officer Johnny Taylor observed Knospler driving over the speed limit in a construction zone at approximately 12:20 a.m., after receiving a call to be on the lookout for a suspect involved in an altercation at Racks. Knospler’s car fit the description, so he initiated a traffic stop at the corner of First and Wolcott Streets, across from the federal courthouse. Taylor pointed out the broken window and asked Knospler if he had gotten into a fight at the bar.

“Well, sir,” Knospler said in the video of the arrest, “I think you know what’s going on here. I’m quite confident you know what’s going on.”

Taylor’s partner, Joshua Peterson, spotted the gun inside a duffle bag on the passenger’s side seat, and they asked Knospler to step out of the car. As Taylor patted Knospler down, Knospler said, “Somebody threatened to kill me.” He then said he would no longer talk without an attorney present. Later, at the police station, Knospler suggested the police officers take note of the glass on his clothes. He asked to press charges against Baldwin before being informed by Detective Sean Ellis that, instead, he was going to be charged with second-degree murder.

Natrona County Assistant District Attorney Joshua Stensaas commissioned a forensic investigation by accident reconstructionist John Daily of Jackson Hole Scientific Investigations. Natrona County had asked Daily to do almost a dozen traffic reconstructions over the prior 15 years, so he was familiar to the prosecution and their team.

Daily’s career spanned 25 years with the Sheriff’s Office in Jackson, Wyoming, including nine years as a detective. He earned a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering from Purdue University, a master’s degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Wyoming, and has been teaching traffic crash reconstruction and applied physics at the University of North Florida Institute of Police Technology and Management for 32 years. Daily has published three textbooks about crash reconstruction and applied physics.

Assistant District Attorney Stensaas, investigating officer Detective Ellis, and Trooper Jason Sawdon met with Daily at a storage garage where police had Knospler’s Chevy Cobalt. They used Ellis as a stand-in for Baldwin, physically posing him in multiple scenarios for how Baldwin could have been positioned when he was shot. Daily concluded that Knospler’s account — that he shot only after Baldwin came through the window to grab the gun — was supported by evidence, namely the fact that the path of the bullet entered just below Baldwin’s neck and exited from his lower back before denting a Ford pickup parked a few spots down. Daily also concluded after examining photos from the scene that the tire tracks in the snow were consistent with a vehicle losing traction or spinning out. This seemed to support Knospler’s claim that he tried to flee before resorting to gunfire.

Broken glass found outside the driver’s-side door and broken glass throughout the front passenger compartment of the car showed strong force applied to the glass from outside, according to Daily’s final report, as would be the case if Baldwin punched out the glass while Knospler attempted to drive away. Furthermore, the autopsy report showed superficial dicing lacerations to Baldwin’s right hand, forearm, and shoulder. At trial, the State’s pathologist called them blunt-force injuries. These wounds could easily be explained, according to Daily, by Baldwin having punched out the window, then getting his arm far enough into the driver’s-side compartment to slash his upper arm. To account for the glass found outside of the car, Daily believed that Baldwin pulled his arm back from the broken window as Knospler shot, which would have cut his upper arm and pulled fragments of glass outside the car into the new-fallen snow.

Daily’s expert reconstruction of the shooting seemed to match Knospler’s explanation point-by-point.

Daily also considered the prosecution’s theory that Knospler overreacted and shot through the window while Baldwin knocked. If that were the case, Daily concluded, only a small amount of glass would have gone outward and wound up beside the Cobalt. Daily pointed out — and numerous recreations since the trial have shown — that a .45 round even at close distance does not explode a car window. Instead, it tends to punch a .45-caliber-sized hole through the glass, causing a web-like splinter. Car windows then typically fall; the compromised glass can’t support itself and tends to collapse straight down. If Knospler had shot while the window was still intact, some glass would have landed on the ground outside the car, while most would have landed inside the car very close to the driver’s-side door. The glass would not be found scattered through the entire passenger compartment as was the case with Knospler’s Chevy.

After receiving the results of Daily’s reconstruction of events, Natrona County District Attorney Mike Blonigan removed Assistant District Attorney Stensaas from the case. Stensaas was of the impression that the case was not chargeable — that it was clear-cut self-defense in a state that valued personal responsibility for individual safety — and investigating officer Sean Ellis held that same conviction, Daily now says.

Stensaas soon after resigned his position as assistant district attorney.

Instead of dismissing or pursuing lesser charges, Blonigan took over the case personally. Ultimately, the report paid for by the State of Wyoming on behalf of the prosecution, and Daily’s expert testimony were used in Knospler’s defense.

“I don’t know if he had something against me personally, or maybe it was more about notches on his belt,” Knospler says. “I do believe he was a strong anti-military guy.”

“I don’t give a shit who hires me,” Daily says. “I tell it like the physics tells me. Obviously, my findings were not to the liking of [Blonigan]. That’s why Stensaas left the prosecutor’s office.”

Knospler’s mother, Patricia Christensen, also claims that Stensaas told Knospler’s lawyers that he did not want to prosecute the case.

According to a 2019 article in The Daily Caller, Stensaas was conflicted about continuing with the case. “I operate on conviction and belief. I would not stand there and say, ‘I don’t think that this is reasonable,’ if I believed there was any chance that I would have reacted stupidly or poorly in the same situation.”

Contacted last week, Stensaas refused to comment on his opinion of the case and whether it affected his decision to quit his job at the Natrona County District Attorney’s Office. He said he’s been misquoted in the past.

Exactly what happened in the DA’s office that led to a ping-ponging of opinions and Stensaas’ ultimate departure may come to light if Knospler’s latest petition, scheduled for Aug. 11, is granted. Knospler’s new attorney, Jerry Soucie, says Stensaas’ position on the case is critical to their claim that prosecution knowingly presented a false argument.

Knospler doesn’t understand Blonigan’s rationale behind tossing Daily’s report and moving forward without Stensaas.

“I don’t know if he had something against me personally, or maybe it was more about notches on his belt,” Knospler says. “I do believe he was a strong anti-military guy.”

Blonigan did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Shortly after his arrest, Knospler hired Joseph Low IV, a high-profile lawyer and former Marine from Long Beach, California, to represent him at the trial, replacing his initial representation from the local firm of Chapman Valdez. Knospler’s mom, who originally hired the local attorney, disagreed with her son’s decision. Low struck her as cocky, a poor fit to defend her son in front of a Wyoming jury. To his credit, Low has a particular interest in veteran-related cases. He represented Sgt. Jermaine Nelson, a Marine accused of murder for an execution-style killing of combatants in Fallujah, and got the charges reduced to dereliction of duty. At the end of the day, Knospler and his family didn’t lose much sleep over finding a good attorney, though.

“The case was black and white in my mind,” his mother says. “When you look at the evidence, John’s story held.”

With Stensaas and Daily out of the picture, Blonigan recruited Steven Norris, the Wyoming Division of Criminal Investigators firearm and tool mark section supervisor, to testify for the prosecution. Norris focused on gunshot residue and the broken glass.

“Bullet wipe” is a gray or black ring around a bullet hole. The ring is formed by bullet lubricant, byproducts of propellant, traces of bullet metal, and residue in the gun barrel from previous use, according to the National Crime Justice Reference Service. Norris found bullet wipe on Baldwin’s T-shirt. Whether the bullet went through a pane of glass or not should not normally affect bullet wipe at the point of entrance.

When Norris looked for a pattern of gunshot residue, the results were different. There were minimal nitrites on the shirt, which led Norris to conclude that the gun had either been shot from farther than arm’s length or the gunshot residue was deposited on an intervening object, such as the driver’s-side car window.

Norris fired the handgun at woven cloth samples from various distances to get a sense of how bullet wipe and gunshot residue would affect the shirt.

Daily thought this was inaccurate and pointless. Norris tested woven fabric, not the knit kind Baldwin was wearing. Plus, Baldwin’s body spent hours exposed to the falling snow while investigators documented the crime scene. Racks employees and EMTs also moved him from face down where he fell to on his back, wetting and soiling his clothing and possibly removing any residue that could have been left on his shirt.

Norris testified, “What happens to the window, it could be anybody’s guess […] It’s been published that oftentimes glass struck by high-velocity bullets will behave somewhat counterintuitively and they actually break inward towards the direction of the gunshot.”

Norris did not conduct any experiments to back up this claim. Knospler’s attorney, Low, did not conduct any reenactments to test for glass dispersion either.

“Neither side thought it was important,” says Daily, who advocated for the test. “Nobody let me do it.”

After his conviction, Knospler hired a new attorney, Jerry Soucie, who commissioned retired homicide detective Larry Barksdale of the Lincoln, Nebraska, Police Department and then-instructor in the forensics department at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Barksdale performed multiple gunshot reenactments to test a wide variety of possible scenarios, covering the tests Daily suggested while the court case was still active.

According to Barksdale’s Abacus Research report, the reenactments found that glass ejected outward in a circle when a .45 is shot at a tempered glass car window. The broken glass forms “long dagger-shaped shards” — not the small, rectangular pieces of glass found in the vehicle and in the parking lot at Racks.

At the trial, Norris asserted that it was possible the glass was still hanging in the frame when Knospler drove away but was fragile and displaced while he drove.

“There’s just so many ways that the glass could have been displaced that I just don’t feel that the location of the glass is a very strong indication of the actual event sequences that could have happened,” he testified.

In closing arguments, Blonigan said that the dispersal of glass fragments was not reliable evidence.

“This was an altered scene, and it’s an altered scene because Mr. Knospler drove away. He fled.”

Knospler’s defense team felt the wounds to Baldwin’s hands and arms clearly showed the glass had been punched out. Daily insisted on the stand that the wounds on Baldwin’s upper arm indicated he had punched the window, but the prosecution contended that the wounds were superficial and likely caused by Baldwin’s fall to the ground. Pathologist John Carver stated at trial that either possibility could be true, although Low pointed out on cross-examination that Carver did not find any gravel or dirt in the wounds that would be consistent with an injury from a fall.

Carver also testified that there were extremely fine fragments of glass in the skin around the bullet wound — grit similar to the bits in 600-grain sandpaper — seemingly suggesting the bullet went through glass before striking Baldwin. Yet Carver also testified that Baldwin had minute glass fragments lodged in his right hand — consistent with striking a window.

The defense called its own pathologist, Dr. Judy Melinek from the University of California at San Francisco. She pointed out that the trajectory of the bullet, entering near the collarbone and exiting above the buttocks, would not make sense if Baldwin had been standing upright. The trajectory only makes sense if Baldwin was leaning through the window. When Blonigan suggested that the recreation done in the Daily report was not accurate due to Daily allowing for “leeway,” Melinek responded: “There’s leeway, but there’s absurdity.” According to her testimony, Daily’s reconstruction held up. Melinek also believed that the glass embedded in his hand was another indication that he punched through the window, and she rejected the idea that Baldwin’s wounds happened with a fall.

Blonigan dismissed the Daily findings and the Melinek endorsement outright during his closing arguments. “How come the injuries to the hand aren’t greater? How come there’s no fracture of the hand? How come there’s no serious swelling? How come there’s no serious bruising? How come there’s no serious cuts? How come there’s no DNA in the car? When all those negatives add up, it didn’t happen that way.”

With so much of the forensic evidence in dispute, much of the trial centered around character. Lawyers from each side angled to get facts included in the trial about Knospler’s and Baldwin’s behavior and past criminal history. Blonigan was largely successful; Low was not.

Blonigan painted Knospler as a damaged Marine veteran, equating his time in Africa to mercenary work. He also brought up Knospler’s arrest in Mexico in 2008 for not paying cab fare after a night of drinking. For the arrest, the Marines demoted Knospler from sergeant to corporal. Aside from a bar fight in 2002 between Knospler and a fellow Marine (in which all charges were dropped), the Mexico incident was Knospler’s only bad mark during an otherwise stellar career in the Marines.

Baldwin’s criminal history was more extensive. He had been arrested for driving under the influence, as well as for marijuana possession twice, had a charge of interference with a police officer, and garnered 19 counts of felony auto burglary on an evening when he and two friends broke into a series of cars and took phones, stereos, GPS devices, wallets, purses, and cash. Low tried to get this included in Knospler’s defense, but the judge ruled much of that background was not relevant to the case.

A review of Baldwin’s cell phone by police also uncovered Baldwin had apparently watched pornography on the device that day, including child and bestiality porn. Knospler’s lawyers contended research has shown that a proclivity for those sorts of pornographic materials is an indication of potential future violence. Judge Thomas Sullins disagreed and did not allow it to be mentioned in court.

Baldwin was also physically imposing, standing 6-foot-3 and 230 pounds, compared to Knospler’s trim, athletic 5-foot-6 frame — though after his death he was characterized by his community as a gentle giant. One of seven children, Baldwin had a good track record with his employer, Automation & Electronics Inc., and had recently overcome testicular and lymphatic cancer. His obituary in the Casper Star-Tribune described him as “non-combative” and having a “mellow nature.”

Baldwin’s friends who were with him at Racks that evening, as well as his mother, did not respond to requests for comment.

The prosecution’s idea to paint Knospler as a violence-prone mercenary spoiling for a fight may have come from Jim Wetzel, at the time a Casper Police Department detective and later the city’s chief of police.

According to the Abacus Research report — paid for by Knospler’s defense after his conviction — Wetzel told the DA’s office that he had contacted sources he knew in MARSOC, where Wetzel himself served as a Marine. MARSOC representatives denied ever speaking to Wetzel, and no Marine who served with Knospler has come forward to speak ill of his judgment. Wetzel was later fired by the police chief after a vote of “no confidence” from his officers in an unrelated incident.

Knospler’s attorney Low brought one of Knospler’s fellow Marines to the trial, which also opened the door for the prosecution to gain evidence of Knospler’s screw-up in Mexico. Scott Lehman, who served with Knospler in Iraq, told a story about how a child approached their convoy waving an AK-47.

“I remember bearing down and locking in. And I remember John saying, ‘Easy, easy, easy,’ beside me,” Lehman recalled on the stand. With the threat of a weapon present, standard military rules of engagement would have allowed for them to shoot. “And this is a matter of, like, five or six seconds. And then we noticed the kids put the gun down and they ran back behind the house, and it was over. He showed an enormous amount of professionalism, of judgment, of control and of tact while operating as a Recon Marine.”

The witness accounts from Knospler’s time at Racks painted a very different picture. Sonny Pilcher, the owner of Racks before losing the club to tax evasion in 2014, arrived around 5:30 p.m. that evening and found Knospler in the parking lot. Pilcher was immediately suspicious.

“He was just — had his shirt off looking at the sky, dancing around like he was doing an Indian rain dance or something,” Pilcher testified at Knospler’s trial. “Like he was praying to the sky.”

Later, Pilcher confronted Knospler after Knospler had moved his car and asked him if he was planning to rob the bar. “My feeling was that he was casing out the place,” Pilcher said.

Knospler claims he reparked the car because he was afraid his gun and laptop might be stolen, and he denies any shirtless dancing.

Bartender Ashlee Logan testified that Knospler spent much of the night by himself, mumbling under his breath. He gave her the creeps, she said. She also said that she asked one of the bar’s regulars not to leave until after a bouncer arrived, so she would not be alone with him.

Dancer Crystal Mize told the jury that Knospler said “that it didn’t matter to him if someone gets in his way. He’ll take care of them, he’ll shoot them, he’ll stomp their face in the ground, stomp their face in the concrete, it doesn’t matter to him.”

Pilcher, Logan, and Mize left most of these details out of their initial police reports.

Defense Attorney Low decided Knospler would not testify in his own defense. The jury deliberated for approximately two and a half hours, and shortly after 5 p.m., two days before Christmas, they found John Knospler Jr. guilty of second-degree murder. While the verdict was read, several of the jury members openly wept.

“There was silence in the courtroom,” Knospler’s mother remembers. “Dumbfounding. Absolutely dumbfounding.”

Statements from the jury collected after the trial show a tense deliberation. One juror said, “I’m so torn [this case] will haunt me for the rest of my life.”

The jury was instructed to consider second-degree murder and manslaughter charges. In Wyoming, second-degree murder means the killing was not premeditated but showed a reckless indifference to human life. The jury was instructed to first consider this charge, and if found not guilty, to consider a lesser manslaughter charge. In Wyoming, second-degree murder carries a minimum sentence of 20 years in prison compared to manslaughter, which has no minimum sentence with a 20-year maximum.

Blonigan emphasized recklessness in his closing argument to the jury: “Even if Mr. Baldwin broke the window, where is the danger of serious bodily harm or death? As the judge has instructed you, when you take the life of another, it’s when it’s the last alternative, when it’s an absolute necessity.”

In a statement after the verdict, one juror said he believed Baldwin had punched out the window. “Absolutely. Because of the position of how he was bent over when he got shot. He would have been bent over after punching out the window and leaning in. And the cuts and bruising all the way from his knuckles to his right shoulder. You could tell he punched something out.” But he did not think Knospler had been right to pull the trigger. “I understand why Knospler decided to defend himself, but he went too far. Knospler’s car was running, he was inside, maybe asleep, but he was sitting in the car and he could have driven away but didn’t. He is a combat veteran and shouldn’t have been that scared.”

Knospler’s girlfriend, Fre, who sat in on the entirety of the trial, was struck by the jurors’ response when issuing the verdict. “Three ladies on the jury turned around and started bawling, crying,” she says. “Now, I know if this guy murdered somebody with intent, I would not feel sorry for him going to jail. I’d be like, ‘He got what he deserved.’ But these ladies were crying. None of this makes sense to me.”

“There was silence in the courtroom,” Knospler’s mother remembers. “Dumbfounding. Absolutely dumbfounding.”

Since the conviction, allegations of jury tampering have surfaced online. The jury foreman, Kevin Huber, was an attorney who had previously worked alongside Blonigan’s wife at the law firm of Williams, Porter, Day, and Neville, PC. While Huber and Blonigan both acknowledged the connection during the jury selection process, Low did not object to Huber’s inclusion on the jury.

After the trial, a female juror in her statement said Huber dominated the deliberations and refused to allow for any alternate theories other than what the prosecution presented. “I yelled at Kevin that we spent seven days in a courtroom and you summed it up in five minutes. That’s bullshit. We would have been back in five minutes if it hadn’t been for me and [another two jurors] arguing with him.”

Another juror said, “I really didn’t like the idea of having a former defense attorney on the jury. I think most of the women were swayed by him. He certainly was a driving force in the way the panel went.”

Huber did not respond to requests for comment.

At the trial, Knospler’s father, John Knospler Sr., did not mince words with the press about his feelings regarding the prosecution’s case.

“There seems to be an agenda in this courthouse,” he told the Casper Star-Tribune following the verdict. “I think because he was an out-of-town guy, this was a chance to make an easy kill for these guys.”

Low represented Knospler again for his initial direct appeal to the Wyoming Supreme Court in July 2015, despite concerns within the family that the California attorney was too far removed from the Casper, Wyoming, jury. The court transcript from the murder trial is filled with the trial attorney attempting to sound folksy and relatable.

In January 2016, that appeal attempt failed. “We went back to the drawing board,” says Knospler’s current attorney, Jerry Soucie. Knospler’s new legal team filed for post-conviction relief to the District Court, claiming ineffective counsel. The district court found that Low was an experienced trial lawyer who had presented sufficient expert evidence and dismissed the petition.

Knospler’s team then asked, post-trial, for DNA testing to be done to establish whether Baldwin had grabbed the gun and thus caused Knospler to fear for his life. The 1911 had a stovepipe jam when found in Knospler’s passenger-seat duffle bag. A stovepipe jam is when a spent cartridge fails to eject and sticks upright between chamber and slide, like a stovepipe. The post-trial Abacus Report commissioned by Knospler’s new counsel shows six reenactments of the shooting suggesting that the malfunction could have happened due to the ejection port being blocked by Baldwin’s hands grabbing for the gun. That could also explain why the magazine release on the .45 was depressed — the magazine had dropped about 1-inch from the magazine well when police stopped Knospler. The District Court refused the DNA testing request.

In 2019, Soucie filed a third petition, claiming prosecutorial misconduct, ineffective counsel, and violation of due process rights. The District Court dismissed it on procedural grounds, but the Wyoming Supreme Court remanded the matter back to the District Court for a further evidentiary hearing. That preliminary hearing is scheduled for Aug. 11.

Perhaps most frustrating to Knospler’s friends and family is how the law has changed in Wyoming since his guilty verdict. In 2018, the state passed a Stand Your Ground law that has the potential of exonerating Knospler if retroactively applied to his case.

Forensic investigator John Daily believes an innocent man is in prison, too. Daily petitioned then-Gov. Matt Mead to pardon Knospler, but the letter went unanswered.

Meanwhile, Knospler sits in a Wyoming prison, hoping his case will be heard again. He’s getting by — focused, according to his girlfriend, Fre. He earned his bachelor’s degree while in prison and is now working toward a Master of Business Administration.

“He’s a Reconnaissance Marine,” Fre says. “He keeps himself busy.”

The last chance for Knospler to argue that his case should be reconsidered is Aug. 11. For the former Recon Marine, 30 to 50 years in prison is on the line.

“John is better than me in every way, and he always has been,” says his old Marine buddy Mull. “I can’t believe he’s in prison. It breaks my heart every day.”

Maggie BenZvi is a contributing editor for Coffee or Die. She holds a bachelor’s degree in political science from the University of Chicago and a master’s degree in human rights from Columbia University, and has worked for the ACLU as well as the International Rescue Committee. She has also completed a summer journalism program at Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism. In addition to her work at Coffee or Die, she’s a stay-at-home mom and, notably, does not drink coffee. Got a tip? Get in touch!

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.