Two Red Army Veterans On Freedom and Why It’s Always Worth Fighting For

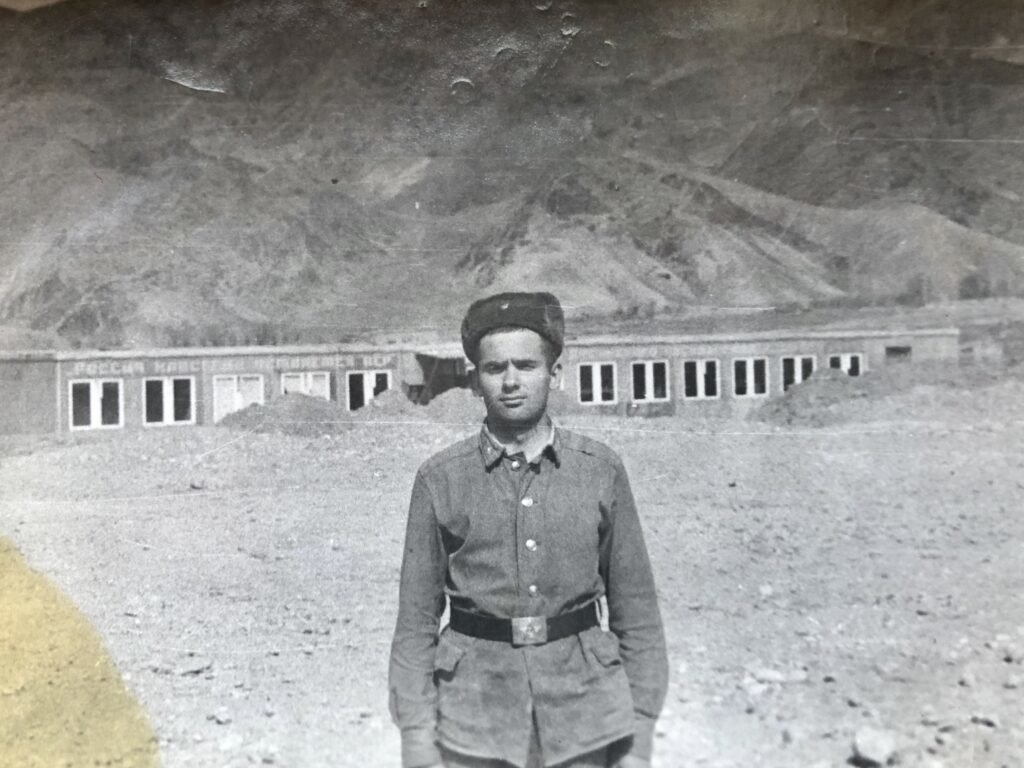

Valeriy Deriy, center, during his service as a Soviet army soldier in the 1980s. Photo courtesy Sergiy Deriy.

They call it the “Island of Death.”

At this spot on the western side of the Dnieper River in central Ukraine, some 30,000 Soviet soldiers died under Nazi artillery during World War II. Yet, on this hot June day, there’s nothing to suggest that this particular place was once on the deadliest front of the deadliest war in human history.

“What horrors happened here,” says my 55-year-old Ukrainian father-in-law, Valeriy Deriy, who is a Red Army veteran of the Cold War. “Can you imagine?”

I cannot.

We’ve hired a zodiac boat for the day, embarking from a yacht club in the riverside town of Horishni Plavni. To get to the so-called Island of Death, our captain weaves through narrow, overgrown channels that branch off the main course of the Dnieper River.

Tucked away in a dense forest on the island, there’s an old Soviet war memorial. You’d hardly notice it from the water, unless you knew what to look for. Valeriy explains that one can still find evidence of war in the surrounding woods. Old artillery pieces, bullets, rifles, and boots. That sort of stuff.

“Some people want to forget the past. But it’s impossible,” he tells me. “It’s always there.”

Between August and December 1943, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union fought the battle for the Dnieper River. It was one of World War II’s largest battles, comprising some 4 million soldiers stretched along a nearly 900-mile-long front.

After Nazi Germany’s defeat at the Battle of Kursk, the Soviets pressed their advantage and pushed the Nazis back across Ukraine. The third longest river in Europe, the Dnieper — which runs roughly north to south down the middle of Ukraine to the Black Sea — was a natural physical obstacle for the advancing Red Army.

The Nazis took to the heights on the western bank to set up their artillery, which they used to devastating effect. The Red Army crossed the river under heavy fire, improvising makeshift means to get across. Soviet losses were staggering — accounts vary, but roughly 400,000 Red Army soldiers died in the Dnieper River battle of 1943.

The Other Side

Earlier, Valeriy and I stand at a spot on the opposite, eastern bank of the Dnieper River.

“My great-grandfather said the water ran red with blood in the war,” Valeriy says as we stand on the riverbank, looking to the other side.

Valeriy explains that his great-grandfather fought in that Dnieper River battle, and he crossed the river at this very spot. Right where we’re standing. I’m left a bit speechless.

His great-grandfather couldn’t swim, Valeriy continues, but Soviet commanders would have him shot if he’d refused the crossing. So he held on to a log for flotation and kicked his way across. Somehow, he survived.

“It was October, and the water was already very cold,” Valeriy says, shaking his head. “What a nightmare.”

Today, at this spot where so many died in World War II, there’s a simple old Soviet memorial crumbling, halfway reclaimed by the forest. A dilapidated Soviet tank and artillery piece sit in the foliage, too. But that’s it. You have to rely on your imagination to appreciate what happened here.

There’s not a cloud in the sky and the hot breeze feels good on my face. On a day like this, it’s hard to appreciate what happened here about 77 years ago. I can hardly imagine the fear felt by Soviet soldiers as they stood at that same spot on the river shore, looking to the far side like lost souls about to cross the River Styx.

And then I remember what it was like to stare across no man’s land in eastern Ukraine. I remember the fear I felt under the Russian artillery and sniper shots. And I imagine, at least a little, what those Soviet soldiers must have felt.

The trench lines in Ukraine’s eastern Donbas region — where Ukrainian troops have fought a war since 2014 to keep a Russian invasion force at bay — are only about five hours away by car. We could be there by dinner, if we wanted to.

True, we’re much too far from the trenches to hear the daily rumble of battle, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist. The war is always there.

Standing on the riverbank, Valeriy says to me: “History has been hard on Ukraine. But things will get better. We’re fighting for our democracy, just like your country did. And we’ll win it, too. Just like you did. I still have hope that my daughter and my grandchildren will see an amazing, free Ukraine.”

Still looking across the river, facing the same divide his great-grandfather once faced, Valeriy adds: “We’ll get there.”

The Past

Valeriy never served in Afghanistan. He was posted instead to East Germany and worked in signals intelligence, a specialty that paved the way for his future civilian career as a German language interpreter.

“It was an unwritten rule in the Soviet army that only one brother would have to be in Afghanistan at a time,” Valeriy explains. “And my brother went in my place.”

Valeriy’s older brother, Sergiy, was drafted into the Red Army and served in the war in Afghanistan from 1982 to 1984.

In fact, both brothers had volunteered for the war. But their mother had secretly gone to military officials and asked that only one son be allowed to go. Sergiy ultimately volunteered without Valeriy’s knowledge. It wasn’t until their mother died in December 2012 that Valeriy learned the truth.

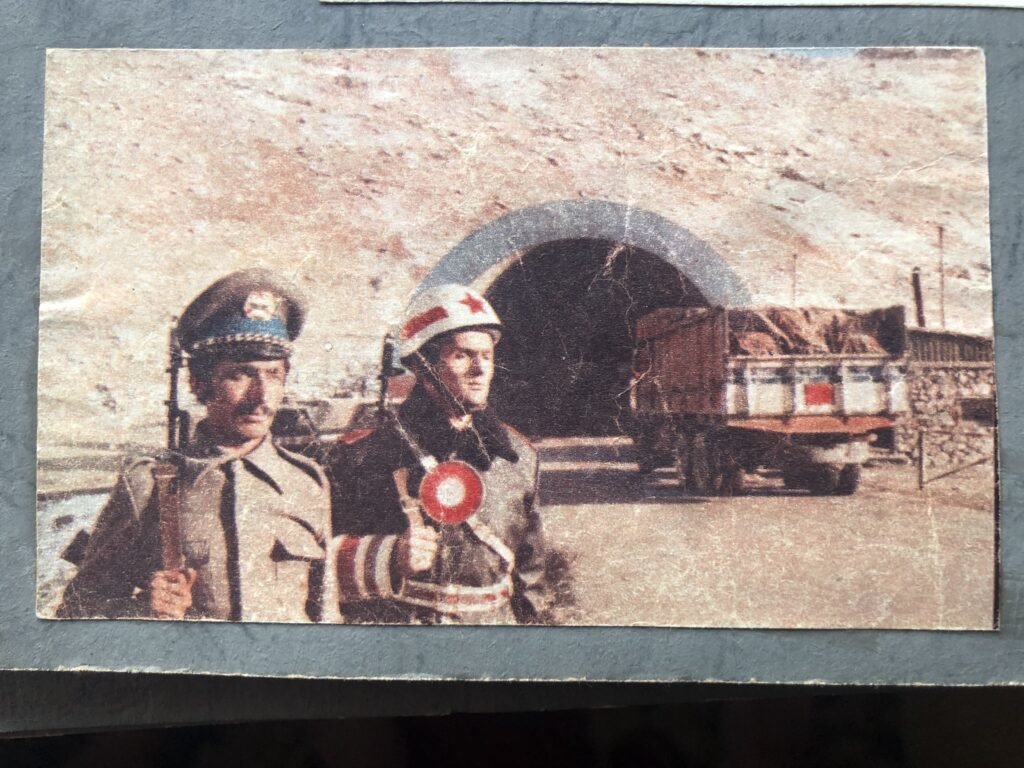

Sergiy was a sergeant in a signals unit deployed near the Salang Tunnel in the Hindu Kush Mountains. The combat he experienced was terrible, Sergiy tells me, but he doesn’t go into much detail about the war very often. And when he does, his eyes adopt a distinctly distant look, as if he’s looking past me, in an attempt to articulate memories that no words could ever really recreate.

Today, both Deriy brothers live in the town of Horishni Plavi — it’s where my wife, Lilya, grew up.

On a warm June afternoon, our family gathers at a park by the Dnieper River to grill shashlik — Ukraine’s version of a barbecue. Both Sergiy and Valeriy are wearing NASA baseball caps, gifts from me and my wife.

It’s the first time we’ve all been together since the coronavirus lockdown was lifted on June 5, and we’re in good spirits. We make toast after toast until our legs are a little wobbly. We’ve brought along an iPhone speaker and grill the meat while we cycle through a playlist of staple rock hits — songs by bands like the Scorpions, Led Zeppelin, Metallica. That’s my in-laws’ favorite kind of music. Mine too.

We end up cooking more meat than we could ever hope to eat in a day. And we maintain a steady pace with the cognac toasts. And, as it’s prone to do, the conversation between Valeriy, Sergiy, and myself returns to the ongoing war in Ukraine’s east.

“The Russians were never our friends. Stalin invaded us, and now Putin has, too,” Sergiy says. “The only county that ever really cared about us was the United States.”

“We’ll never forget what your country has done for us,” he adds, speaking specifically about America’s delivery of Javelin anti-tank missiles to Ukraine.

Then Valeriy abruptly stands.

“Please,” he says, beckoning me to shake his hand, “I want to shake the hand of a citizen of the country that put a man on the moon.”

I stand and shake my father-in-law’s hand and feel proud of my country. And I’m particularly proud that he’s proud of my county, too.

A generation ago, we would have been enemies. Our countries were poised at opposite ends of the earth, ready to unleash nuclear Armageddon to destroy one another.

Today, we are a family.

No One Forgets

Located on the east bank of the Dnieper River, roughly 190 miles southeast of Kyiv, Horishni Plavni was founded by Soviet youth volunteers in 1960 as a place to live for workers in the nearby iron-ore mines.

Originally, the city’s name was “Komsomolsk,” a reference to the All-Union Leninist Young Communist League, or “Komsomol.” The town was renamed Horishni Plavni in 2016 as part of Ukraine’s decommunization laws—a set of measures that went into effect in 2015 to curb Russia’s cultural influence.

Across the country, all Soviet-era names of settlements and roads have been changed to new Ukrainian ones. All reminders and relics of the Soviet Union have been removed or made illegal — including playing the Soviet national anthem and displays of the hammer and sickle flag.

Horishni Plavni’s main thoroughfare was once called Lenin Street. Now it’s named Heroes of the Dnieper River Street. The statue of Vladimir Lenin that once stood in the city center is gone. Only an empty pedestal remains — a common sight in Ukraine these days.

Yet you can’t totally erase the past. World War II is too deeply ingrained in Ukraine’s national psyche, and its physical environment, to ever be forgotten.

Soviet-era war memorials still stand around Horishni Plavni. At a riverside park, children play on the marble ramps of a towering, Soviet-era war memorial. In a nearby field, a row of Soviet tanks are on permanent display. Teenagers sit in the shade of the turrets and drink beer and listen to music.

Despite all their years living under Soviet propaganda, my father-in-law and uncle-in-law have a surprisingly pro-American perspective on the war.

“The Soviet Union could have never won without American help under lend-lease,” Valeriy tells me, referring to the American policy from 1941 to 1945 to provide materiel assistance to the Soviet Union’s war effort.

“And thank God the Allies landed in France,” Valeriy adds. “Otherwise Stalin would have taken over all of Europe.”

No War Ever Ends

After our shashlik picnic is over, Sergiy visits his brother’s apartment, where my wife and I are staying. He brings with him a photo album from his time in the Soviet army, including his deployment to Afghanistan in the 1980s.

I’m thrilled to have a look and listen to his stories from the war.

Sergiy recalls how his commander in Afghanistan justified the Soviet war by the need to defend the Soviet Union from U.S. nuclear missile strikes.

“We were told that America was evil, and that we were fighting in Afghanistan to defend the world from America,” Sergiy tells me. “It was all a lie, of course.”

Incredibly, Sergiy bears no ill will toward the country — my country — that was responsible for the death of many of his comrades.

“The Soviet Union did the same to America in Vietnam,” Sergiy says of America’s covert effort from 1979 to 1989 to arm and finance Afghanistan’s mujahideen fighters to fight against the Soviets. “It was the Cold War, and we were enemies. And that’s what enemies do to each other.”

Now, Sergiy has welcomed me — an American veteran of another war in Afghanistan — into his family with open arms. More than that, I’d even say that Sergiy and I share a special bond because we share a common battlefield. We remember the same places, and in some cases, the same enemies. Sometimes, as I’ve learned, former enemies actually have more in common with each other than they do with their fellow citizens who know nothing about war.

As he goes through the old photos, Sergiy’s face flashes with various contradictory emotions. Pride and pain. Nostalgia and regret. For Sergiy, war was both the worst and the best experience of his life. Therein lies that great paradox that faces all soldiers who’ve home to live in peace.

If war was so terrible, why do we sometimes miss it?

Sergiy, for his part, remembers his friends from the army fondly. But there’s a dark cloud, too, that hangs over every good memory.

“The Soviet Union lied to me. They lied to all of us,” Sergiy says as he flips through the photo album’s pages.

He pinches his lips and slowly shakes his head.

“They wasted so many lives,” he adds.

Soldiers rarely fight for the reasons dictated to them by the governments that send them to battle. Rather, once the bullets start flying, a simple sense of duty to defend one’s friends, and to not disappoint their expectations, is what inspires one to act courageously.

Yet, once soldiers are separated from their wars for a while — either by time or by distance — the moral clarity of duty may erode, leading them to question the justice of their individual actions in combat. The simple kill-or-be-killed morality of combat no longer shields them from thoughtfully considering the consequences of the things they did in war.

In many ways, life in peace is much more complicated than life in war. That was certainly true for my uncle-in-law. Although Sergiy came through the war in Afghanistan physically unscathed, he was left irrevocably jaded about Soviet communism.

Hope

In 1985, just a year after his discharge from the Soviet Army, Sergiy began law studies at Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, Ukraine’s premier university.

“I felt so at peace. Finally, no war, no suffering. Only a bright future,” Sergiy recalls of his arrival in Ukraine’s capital city to begin his studies.

But it didn’t last. In April 1986, an explosion ripped through reactor No. 4 at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant.

The Chernobyl plant is located only about 60 miles north of Kyiv. And so, spooked by the threat of radiation, Sergiy was unsure whether he should stay in Kyiv to finish his law degree. The reborn optimism and happiness he’d felt just a year earlier, fresh from his wartime service, quickly gave way to feelings remembered from the war — dark feelings that he’d wanted to forget forever.

“When I was in Afghanistan, I always felt like death was chasing me,” Sergiy remembers. “And when I came back to Ukraine, I thought I could be free from that fixation on death. But Chernobyl happened, and here death finally caught me. A long and painful death. I remember I said to myself, ‘How ironic, death didn’t catch me in the war, but it did in civilian life.’”

Sergiy ultimately stayed in Kyiv to finish his law degree. After graduating from law school in 1991, he returned to his hometown of Horishni Plavni (then called Komsomolsk). The Soviet Union broke apart that year, further upending his world.

When Ukraine’s economy subsequently collapsed in the 1990s, Sergiy ultimately abandoned his law career and took up work as a hired hand. It was his only option to make a living. He never went back to practicing law.

My uncle-in-law, who is a devoutly religious man, has struggled with his demons from Afghanistan. And his family life has had its ups and downs. But he’s never given up hope for his country, even as Ukraine has gone through revolutions and an unfinished war to finally free itself from Russian overlordship.

“I try to stay positive, despite everything that’s happened to our country,” Sergiy says. “It would be so wrong not to believe in our future. I always have hope. It’s just a matter of time. Our future generations will be truly happy and free.”

Moral Courage

As young men, Soviet propaganda told Valeriy and Sergiy that America was their mortal enemy. Yet, as older men, they’ve both shown the remarkable moral courage to abandon their former worldviews and embrace the promise of democracy.

Above all else, Valeriy and Sergiy now believe in the justice of freedom and democracy rather than conformity and communism. And the two Red Army veterans wholeheartedly believe that the United States is a force for good and a beacon of hope for freedom-loving people around the world.

It’s true that history hasn’t been kind to Ukraine, and my in-laws have not led easy lives.

Yet in spite of everything, their faith in America remains unbroken. And, with America’s promise lighting the way, they still extoll the justice of their own country’s democratic path, no matter its attendant hardships.

In the end, they choose to reject their Soviet past but not forget it. When the work of building a democracy gets tough, as it so often does, they look to the past to remember what they’re working so hard to achieve.

“Democracy hasn’t been easy, but I’d rather live as a free man than go back to the way things were before,” my father-in-law says.

Freedom, after all, usually means more to people who’ve experienced the alternative.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.