The Red Ball Express: How African American Truck Drivers Supplied Patton’s 3rd Army in World War II

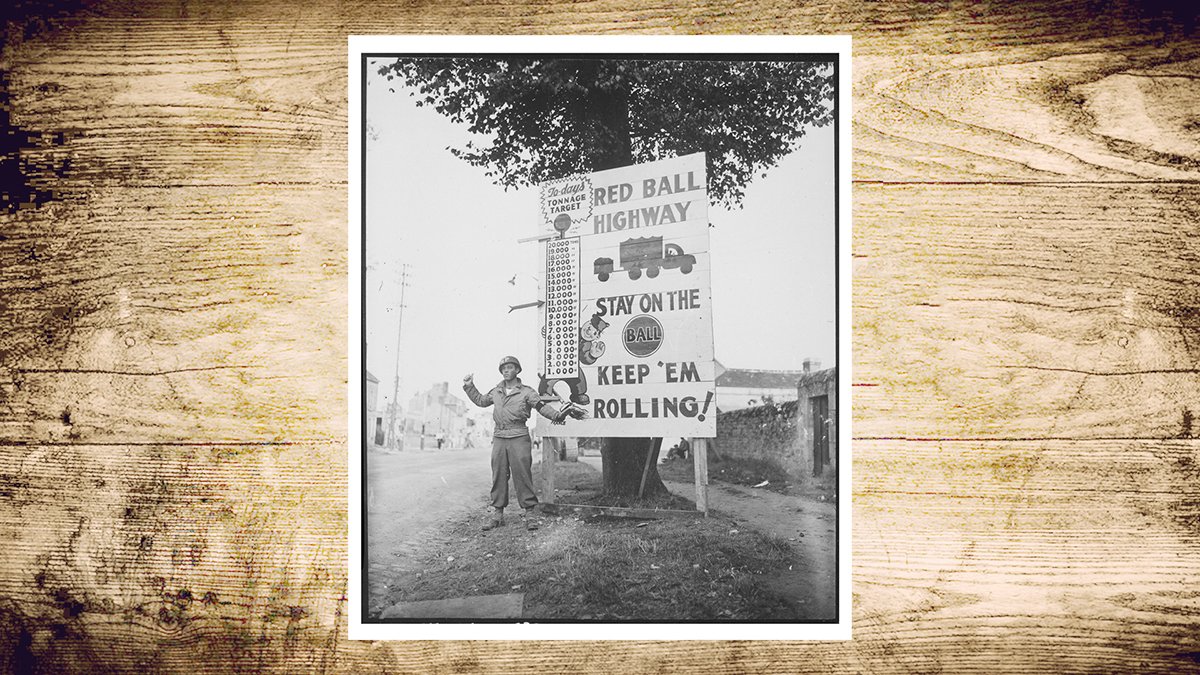

Military Policeman and sign posted along the Red Ball route. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Composite made by Matt Fratus/Coffee or Die Magazine.

Six weeks after more than a million American, British, and Canadian troops invaded Normandy, France, on June 6, 1944, Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley launched Operation Cobra. The mission was to break out from the stalemate where the Allies were wedged in a bridgehead roughly 50 miles wide and 20 miles deep. At the front of the charge through southern Normandy was Lt. Gen. George Patton’s 3rd Army. Early on, with Patton covering more than 80 miles a day in pursuit of the retreating Germans, a lack of logistics created what war correspondent Ernie Pyle called a “tactician’s hell and a quartermaster’s purgatory.”

“On both fronts an acute shortage of supplies — that dull subject again! — governed all our operations,” Bradley wrote in his autobiography, A General’s Life. “Some twenty-eight divisions were advancing across France and Belgium. Each division ordinarily required 700-750 tons a day — a total daily consumption of about 20,000 tons.”

Prior to D-Day, Allied aircraft had destroyed the French railway system to prevent German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel from supplying his troops along the French coastline. Since bridges, trains, and railroads were damaged or destroyed and the Germans had controlled the ports of northern France and Belgium, Allied commanders put forward an alternative solution.

In August 1944, Brig. Gen. Ewart G. Plank along with other Allied commanders developed a dedicated supply chain using a convoy system to bring logistical support to the front lines. “Let it never be said that [a lack of supplies] stopped Patton when the Germans couldn’t,” Plank famously said in his declaration.

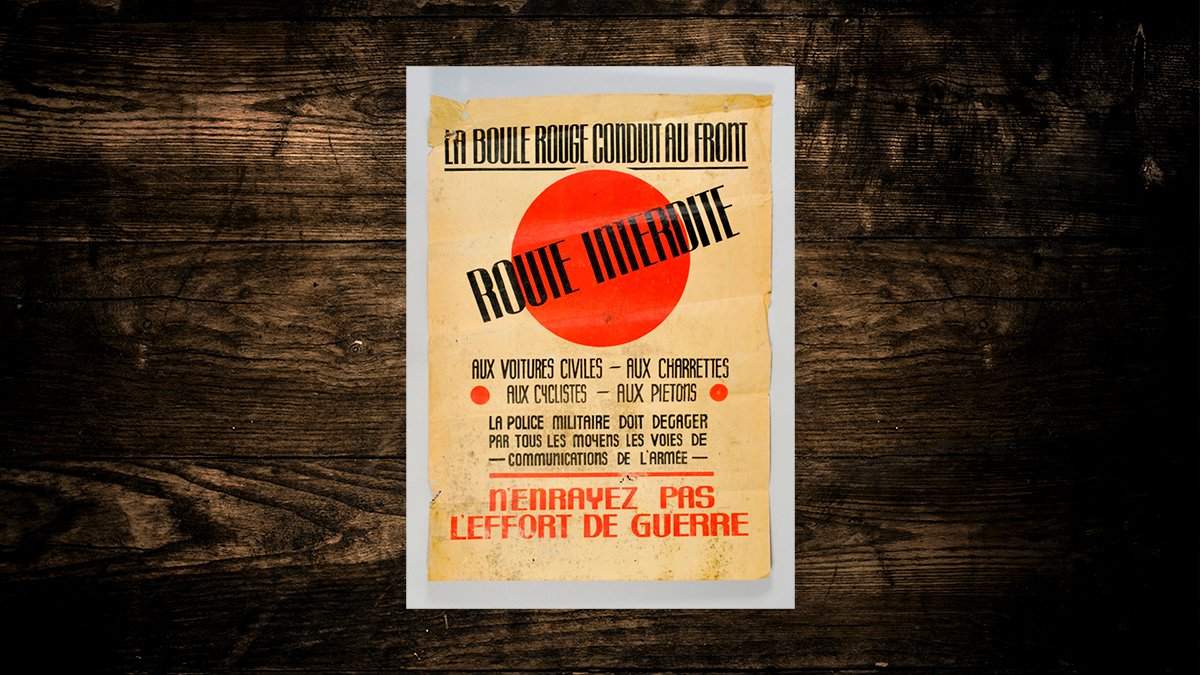

This convoy system became known as the Red Ball Express, or the Red Ball Line. It was named after an old railroad term used in the United States for priority express trains — other trains had to yield to the trains that had the red ball painted on them. The Red Ball Express highways were two parallel one-way routes open only to military traffic. The northern route was used for delivering supplies, and the southern route was used for returning convoys that often transported German prisoners of war.

Although some convoys had makeshift gun trucks with .50-caliber machine guns, largely these convoys drove unprotected along the 700-mile route. These trucks were at risk of being shot to pieces by enemy aircraft, blown up by land mines in the road, or shot at by enemy patrols. Soldiers would put sandbags on the truck floors for an additional layer of protection.

“We had to drive slowly at night because we had to use ‘cat eyes,’ and you could hardly see,” said Red Ball Express driver James Rookard in an interview with the Cleveland Plain Dealer in 1999. Masking narrow slits onto truck headlights reduced the output to a dim beam to keep convoys from being spotted. “If you turned on your headlights, the Germans could bomb the whole convoy. So we had to feel our way down the road.”

Some 6,000 Army trucks carried food rations, gasoline, ammunition, and supplies 24 hours a day, seven days a week, for 82 days straight. Over 75% of the Red Ball drivers were African Americans.

“The Red Ball Line is the lifeline between combat and supply,” Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower said in a message sent to officers and enlisted men from the Red Ball Express in October 1944. “To it falls the tremendous task of getting vital supplies from ports and depots to the combat troops, when and where such supplies are needed, material without which the armies might fail.”

The Red Ball Express was vital to Patton’s success, and in just three months of operations they brought 412,000 tons of supplies to the front. In 10 months, Patton and the 3rd Army raced through France, Belgium, Luxembourg, Germany, Czechoslovakia, and Austria, to victory.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.