‘Do You Remember the Battle of Ia Drang?’ — A Salute to Joe Galloway, My Friend and Mentor

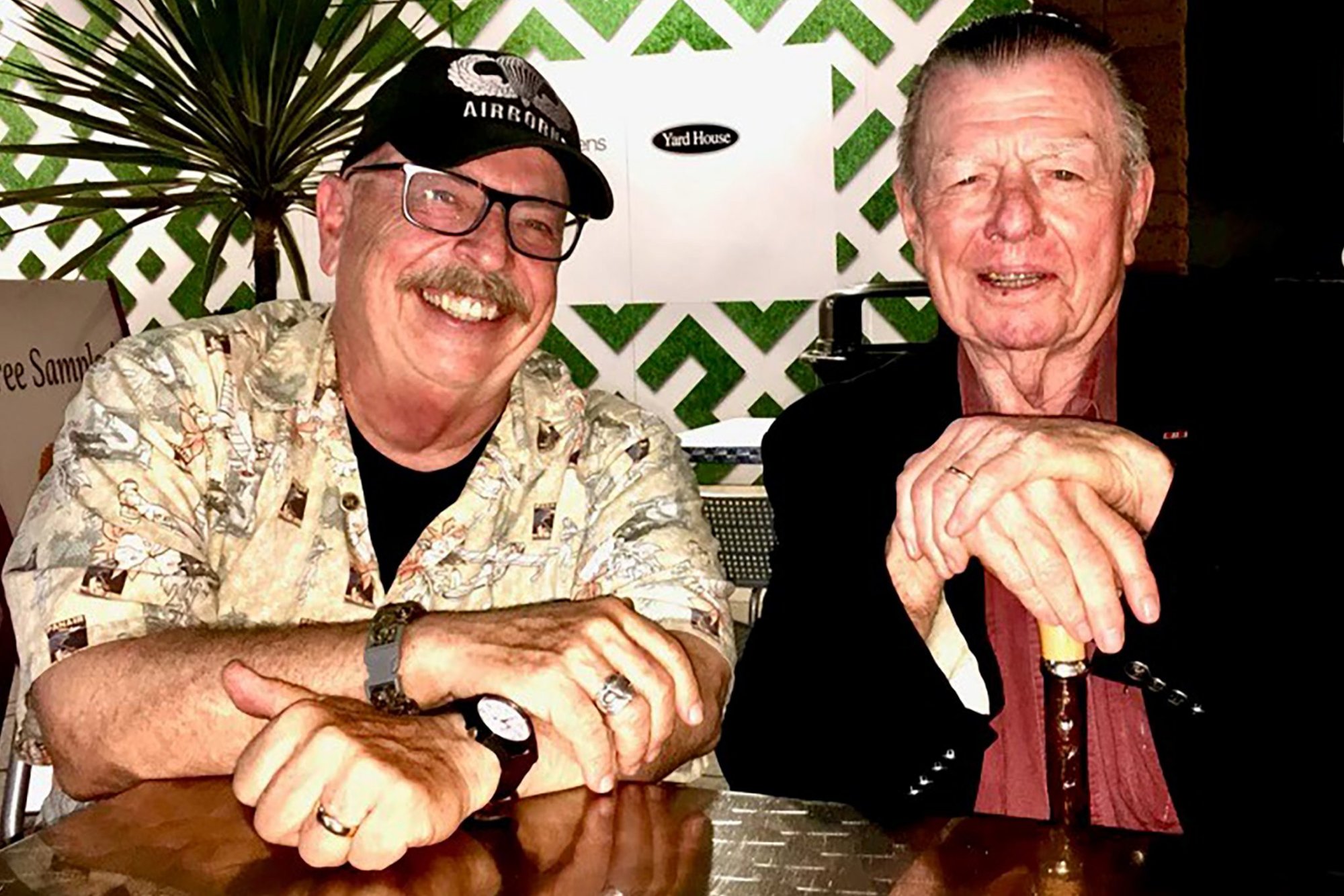

Army Airborne veteran Dennis Anderson, left, with legendary war correspondent Joseph L. Galloway, the “Ernie Pyle of Vietnam.”

Do you remember the Battle of Ia Drang?

The words echoed loudly in my memory after a journalist friend called me and broke the terrible news that my friend and mentor — one of America’s finest journalists — passed away Wednesday, Aug. 18.

The year was 1984, and Joseph L. Galloway was a craggy mass of leathery skin and hard-nosed character. We sipped bottles of Singha beer together and munched on crispy mee krob noodles and chicken satay. It was a hot summer afternoon in a Thai restaurant jammed into a gritty industrial strip of the San Fernando Valley. It was not Tiger beer, but then, we were not in Vietnam. We were in Los Angeles nearly 10 years after the fall of Saigon. Joe was at home in LA — as much as he had been in the Central Highlands of Vietnam, or the streets of Moscow during the Cold War. He had been bureau chief for United Press International in all three places. He was the essential globe-trotting, veteran journalist.

We were drinking Thai beer that afternoon in 1984, but Joe Galloway’s mind was time-traveling in Vietnam, the way veterans’ minds often do. He was a civilian noncombatant, but most of his battle buddies considered him every bit the veteran. It took me a few minutes to catch up with him, as I was wallowing in the miseries of the Los Angeles bureau of UPI, bitching about the boss’s inability to recognize my sterling qualities as a newsman.

Joe chuckled at that, and he chuckled at me. His vantage point was larger than boss problems, or the unpleasantness of starting your day job around midnight. That was just the news business.

“You remember the Battle of Ia Drang?” he asked me as we ordered another round.

No, I did not. I asked him the year it happened. I never served in Vietnam. My Army time was spent in NATO watching the East German border. Joe had spent years in Vietnam. So, what year?

“Ia Drang happened in ’65.”

I told Joe I was 12 years old in 1965, and he guffawed. We lifted our glasses, in salute of my youth and innocence.

“It was the biggest battle of the Vietnam War,” Joe offered. “Biggest fight, and I was there on the ground with 1st Cav.”

More than that, he was there with the 7th Cavalry Regiment, George Armstrong Custer’s outfit. Like Galloway, “The Cav” was made up of the larger-than-life stuff.

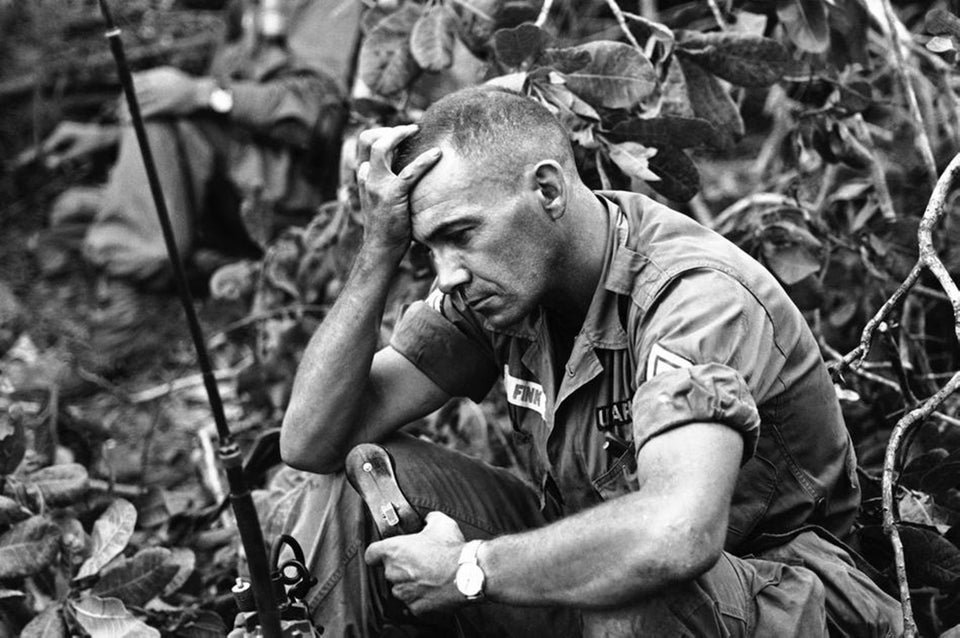

This was not another war story. It was Joe’s story. The Battle of Ia Drang was the story he would write from lived experience, a reporter with an M16, on the ground with the commander, Lt. Gen. Harold Moore. As a lieutenant colonel Moore commanded the 1st Battalion of the 7th Cavalry as it withstood charge after charge from three North Vietnamese Army regiments in the Ia Drang Valley.

Joe was the only reporter on the ground who helicoptered in with the troops. That was how Joe worked. No Saigon news conference follies. He didn’t follow the troops. He moved in with them.

“I’m writing a book about it,” he told me. “Going to be a helluva book, because it’s a helluva story.”

Meeting me in the strip mall eatery on a Saturday afternoon was more than a professional courtesy. It was a kindness. Joe was the reason I was hired into United Press International. He had a soft spot for veterans, and he cheered mightily when I was taken on at UPI.

“You’ll probably curse the day you hired on when you’re doing the midnight trick in Minneapolis up to your butt in snow,” he wrote to me.

Turned out I missed the midnight in Minneapolis duty post for UPI. I worked in Washington, DC, and Los Angeles, both tough towns to cover but lots of big stories from the first day to the last. That was something we both liked and chased — the big story.

I remember Joe’s faraway look talking about the Ia Drang battle.

Doesn’t every reporter have a book he wants to write accumulating pages and dust in a steel desk drawer? I thought.

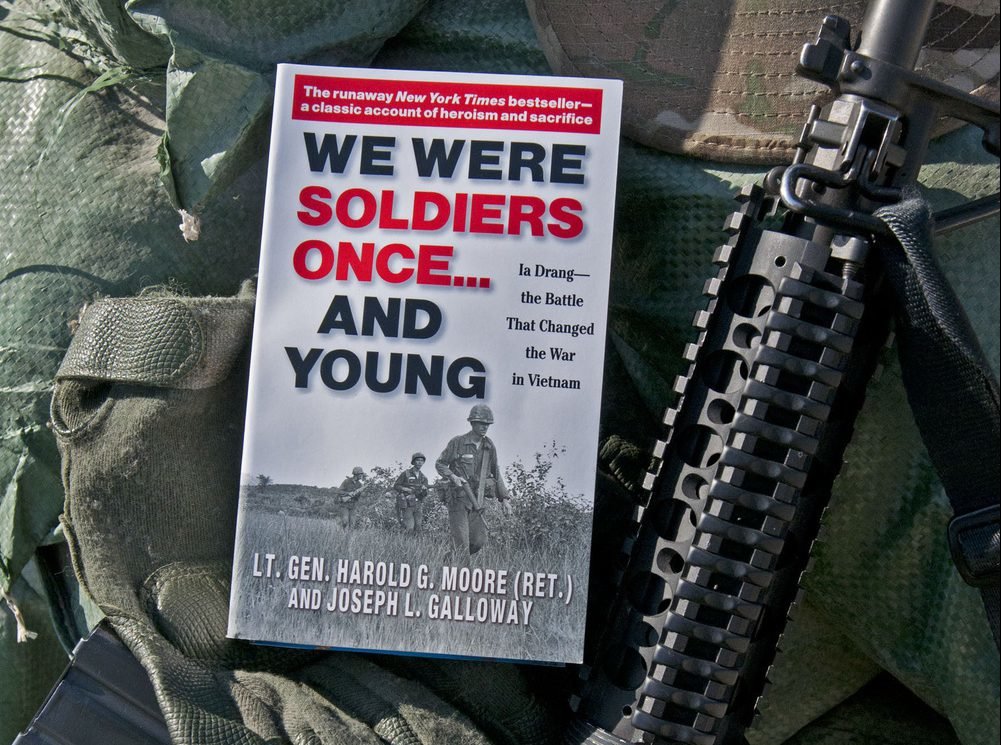

But Joe actually wrote his book, reconstructing the battle he lived through in painstaking detail with help from his brother-in-arms, Lt. Gen. Moore. And Joe was right. It was a helluva story.

Since its publication in 1992, We Were Soldiers Once … and Young has remained in print nearly 30 years later, selling more than 1 million copies. It has also been required reading at West Point and the Marine Corps Commandant’s List for Career Level Enlisted.

The book was testimony of the more than 200 soldiers from the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 7th Cavalry who died in the battles at LZ X-Ray and LZ Albany in Ia Drang. Thousands of North Vietnamese troops died in the Ia Drang campaign. The Americans’ names make up Panel 3 East of the Vietnam War Memorial in the nation’s capital.

Joe’s book was a New York Times bestseller, with Vietnam correspondent David Halberstam calling it “A stunning achievement — paper and words with the permanence of marble. I read it and thought of The Red Badge of Courage, the highest compliment I can think of.”

The film We Were Soldiers, based on the book, opened in 2002 not long after the terror attacks of 9/11, and its depiction of both American and North Vietnamese troops fighting with conviction and valor reflected the conviction of Galloway and Moore to “hate the war, but love the warrior.”

Mel Gibson starred as Moore and Barry Pepper as Galloway, but the film’s depiction of Sgt. Maj. Basil L. Plumley by Sam Elliott became an iconic portrait of senior NCO leadership. Plumley will mainly be remembered by soldiers today through Elliott, delivering lines like “No noncombatants today, sonny,” and “Gentlemen, prepare to defend yourselves.” The real Moore, Plumley, and Galloway did their respective jobs danger-close in the battle space as the 1st of the 7th Cav survived the savage encounter with a combination of valor, combined arms, hand-to-hand combat, and backing from air support and artillery.

When I read Joe’s book, I thought back to our lunch in that Thai restaurant in LA.

“Do you remember the Battle of Ia Drang?” he had asked me.

I was caught up in my own professional grievances, and Joe had been trying to tell me about a defining moment in his life. I thought about how much I didn’t know about what Joe had seen and lived through over there. But Joe did what he did best. He chuckled wryly, and encouraged me to persevere.

“Don’t worry about the boss,” he counseled. “Just worry about the story, and you’ll be all right.”

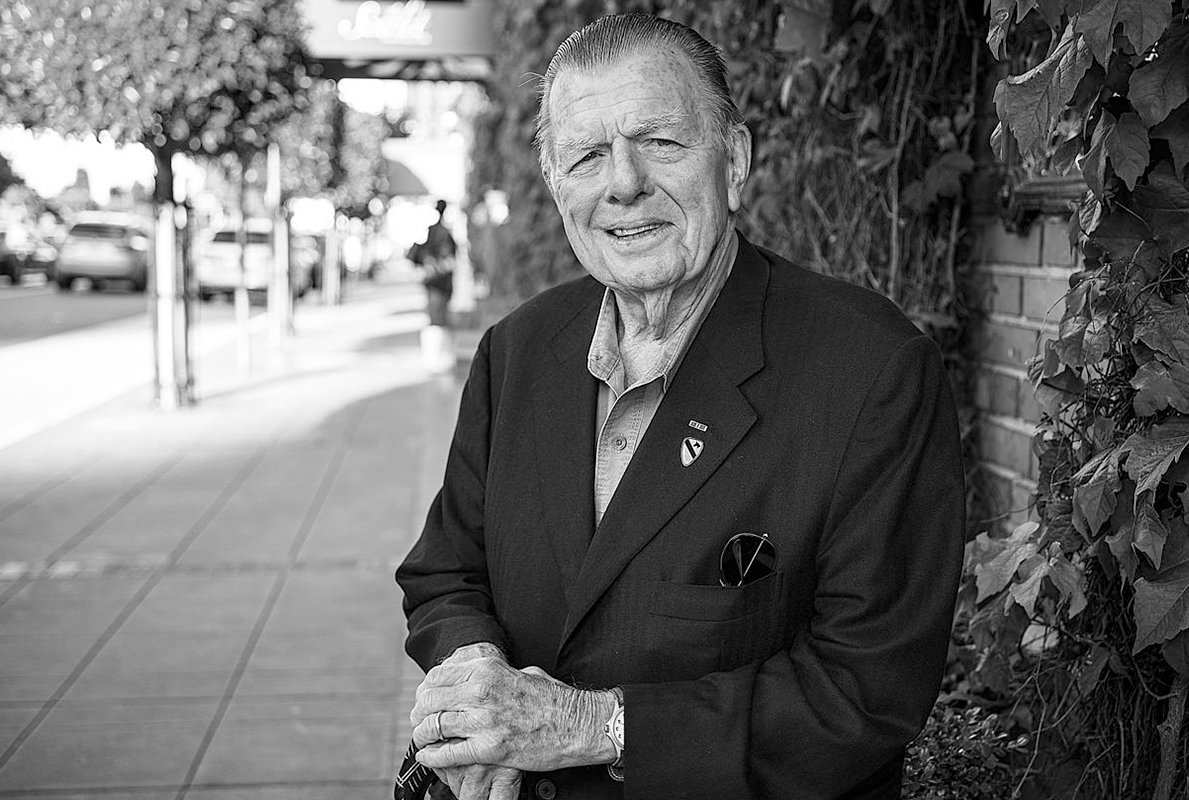

In war reporting, two names set the gold standard for covering the troops — Ernie Pyle in World War II, and Joseph L. Galloway in Vietnam, and beyond. When it came time for me to report in a combat zone, Joe’s advice went in my packing list.

As the drumbeat for war in Iraq speeded up after the attacks of 9/11, then-Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld decreed that reporters could “embed” with units in the field. He wanted some good press for the shock and awe campaign, and the press was in some mad rush to oblige. So many inexperienced would-be correspondents crowded the field that the Pentagon organized a weeklong reporter boot camp dubbed “Camp Snoopy.”

Galloway had plenty of useful advice: “Try to look as much like the soldier next to you as possible,” he told me. “If they see something that sets you apart, you are sniper bait. … Watch the sergeant. If the sergeant drops to the ground, you do too. … Sleep with your boots on. It keeps scorpions and other crawly critters out, and you may have to leave in a hurry.”

When I was embedded with a National Guard unit in Iraq, Joe’s guidelines served me well. He was a great mentor to many American journalists and war correspondents, and he was a fierce champion of America’s Fourth Estate. He was never afraid to speak, or snarl, truth to power.

Joe’s snarling eventually put him sideways with Rumsfeld, the noncombat former Navy pilot who was secretary of defense. Joe gave Rumsfeld such hell in his columns for Knight Ridder and McClatchy News Service that Rumsfeld invited him to the Pentagon for a charm offensive over lunch. It didn’t work. Over the fine china and silver, Rumsfeld asked why Galloway didn’t think he cared about soldiers.

“Because you’ve never had one die in your arms,” Joe responded. According to Joe’s column, Rumsfeld entreated him to lighten up, and Galloway said, in effect, no deal. He was going to keep coming. Galloway reported for another five years after Rumsfeld’s departure. I can tell you this much: A lot of people will miss Joe Galloway. Rumsfeld, not so much, I think.

And Joe went to Iraq, out on the road and on the patrol order with the troops, again and again.

Last month, I attended a reunion of the Society of the Vietnamese Airborne. Two of the Army’s best, retired Gen. Barry McCaffrey, and retired Lt. Gen. John LeMoyne, remembered Joe from their days as captains with South Vietnamese paratroopers, and later when they were general officers running Desert Storm with Gen. Norman Schwarzkopf.

Their first question was “Do you know Joe Galloway?” both of them adding, “He’s a first-rate reporter who told it like it is.”

Well, yes, I did. So long, Joe. Garry Owen. Till Valhalla.

Read Next: Baby Passed Over Gate in Iconic Kabul Image Returned to Parents

Dennis Anderson is a licensed clinical social worker at High Desert Medical Group. An Army veteran and retired journalist, he deployed with California National Guard troops to cover the Iraq War for the Antelope Valley Press. He specializes in veterans and community mental health issues.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.