Exiled From Cuba, He Was Recruited by the CIA To Invade the Bay of Pigs

Roberto Pichardo participated in three covert CIA operations during the Cold War including as a member of Brigade 2506 during the failed Bay of Pigs invasion. Photos by Manny Pichardo and Jim Hawes. Composite by Coffee or Die Magazine.

Roberto Pichardo was still convinced that the Central Intelligence Agency wouldn’t leave him behind, but after three days at the Playa Girón airfield, dodging strafing runs from Cuban military aircraft and waiting in vain for American reinforcements to arrive, he was beginning to worry they might.

Pichardo belonged to Brigade 2506, an exclusive group of Cuban exiles armed and trained by the CIA. In April 1961, under authorization by President John F. Kennedy, Brigade 2506 took part in the infamous Bay of Pigs invasion. Their mission, financed and coordinated by Washington, was to depose dictator Fidel Castro, install a new, Western-friendly regime in Havana, and, ultimately, deal a crushing blow to America’s Cold War adversaries — namely, the Soviet Union, with which Castro was closely aligned. While most historical observers are familiar with the strategic failures that doomed the operation, far less attention has been paid to how the invasion was experienced by the Cuban exiles who carried it out. Pichardo, now 86, and one of the last surviving members of Brigade 2506, hopes his story will shed light on the harrowing events that unfolded on the southwestern coast of Cuba 61 years ago and help preserve the legacy of those who sacrificed everything in the name of freedom.

Castro assumed power over Cuba in 1959 after leading a successful guerrilla campaign that removed the American-backed military dictator Fulgencio Batista from office. Members of the toppled government were persecuted under the new regime, and droves of them were tried and executed by revolutionary courts. Castro’s regime also intimidated and harassed ordinary citizens accused of criticizing him or suspected of having ties to enemy governments. Thousands of Cubans were imprisoned, beaten, and killed in the purge.

Fidel Castro in Washington, 1959. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Composite by Coffee or Die Magazine.

Pichardo was among those who ended up on the regime’s blacklist in the aftermath of the revolution. In August 1960, he was a 24-year-old radio technician servicing military aircraft at the Havana airport. One evening, two officers from Castro’s secret police approached him while he was on the job and began asking questions. The officers accused Pichardo of conspiring with some of his co-workers to support the anti-Castro movement. Despite Pichardo’s insistence that he “wasn’t involved in anything,” the officers threatened to come back to the airport and shoot Pichardo if Cuba was ever invaded.

In Miami, Pichardo soon began hearing rumors of a top-secret CIA-backed army of volunteers being mustered for a mission to bring down Castro.

Shaken by the encounter, Pichardo decided to leave Cuba immediately. He and his family resettled in Miami, Florida, joining a growing diaspora of Cubans fleeing the revolution. There he soon began hearing rumors of a top-secret CIA-backed army of volunteers being mustered for a mission to bring down Castro. The rumors turned out to be true, as Pichardo learned one day when he attended a gathering at the home of a fellow Cuban exile, where he and 11 other Cuban aviation electronic technicians were recruited by the CIA for Operation Pluto (later renamed Operation Zapata).

The CIA wasted no time building its invasion force. By November 1960, Pichardo was undergoing rigorous military training at a secret camp in Guatemala. He and his new comrades, all Cuban exiles, received instruction from CIA officers and frogmen from the US Navy’s Underwater Demolition Teams. They were schooled in the basics of small-unit tactics, guerrilla warfare, and amphibious landings and organized into an assault element. The unit was dubbed Brigade 2506 — a reference to the code numbers assigned to each of its members. Those numbers began at 2500, rather than zero, the intention being to fool Castro’s regime into thinking that the invasion force was much larger than it actually was. In reality, it comprised about 1,400 members.

Roberto Pichardo, second from the right, served as a radio technician for B-26 aircraft. After Pichardo reached the airfield in Cuba during the failed Bay of Pigs invasion he was strafed by enemy aircraft fire. Photo courtesy of Manny Pichardo. Composite by Coffee or Die Magazine.

While the brigadistas were training in Guatemala, the existence of Brigade 2506 — and its affiliation with the CIA — became common knowledge among Cuban exiles in Miami. Word spread widely throughout the community and is believed to have even reached Castro himself. Despite being aware of this, CIA leadership decided to go forward with the operation, and in February 1961, Kennedy gave it the official green light. Pichardo himself says that he never doubted that the mission would succeed, telling Coffee or Die Magazine that at the time he believed the United States was too committed to the cause to fail.

Yet there were indications that Pichardo and his comrades were not being set up for success. On the eve of the invasion, CIA operatives showed the men of Brigade 2506 a series of U-2 surveillance photographs of the beaches along the southwestern coast of Cuba, where the brigadistas would be deposited by boat to begin their fight inland toward Havana. According to Pichardo’s son, Manny Pichardo, who helps curate the Brigade 2506 Museum in Miami, the Cubans “pointed out to the CIA that those clouds in the picture were actually a coral reef.”

The first phase of the plan entailed airstrikes against three Cuban air bases — two located near Havana and one near Santiago de Cuba on the eastern end of the island — the goal being to cripple Castro’s air force so that the seaborne invasion could commence with minimal interference. Next, under the cover of night, an amphibious assault force from Brigade 2506 would hit the southwestern coast, aka the Bay of Pigs. Bolstered by three landing craft carrying the brigade’s M-41 tanks and two more containing a CIA operations officer and a team of UDT frogmen, the brigadistas would conduct over-the-beach assaults at Playa Girón and Playa Larga. Once the airfield was secured, a fleet of B-26 bombers would be dispatched to bombard Castro’s ground forces. In the event that the assaulters needed to retreat, a contingency plan called for their escape into Cuba’s Escambray Mountains, approximately 80 miles away.

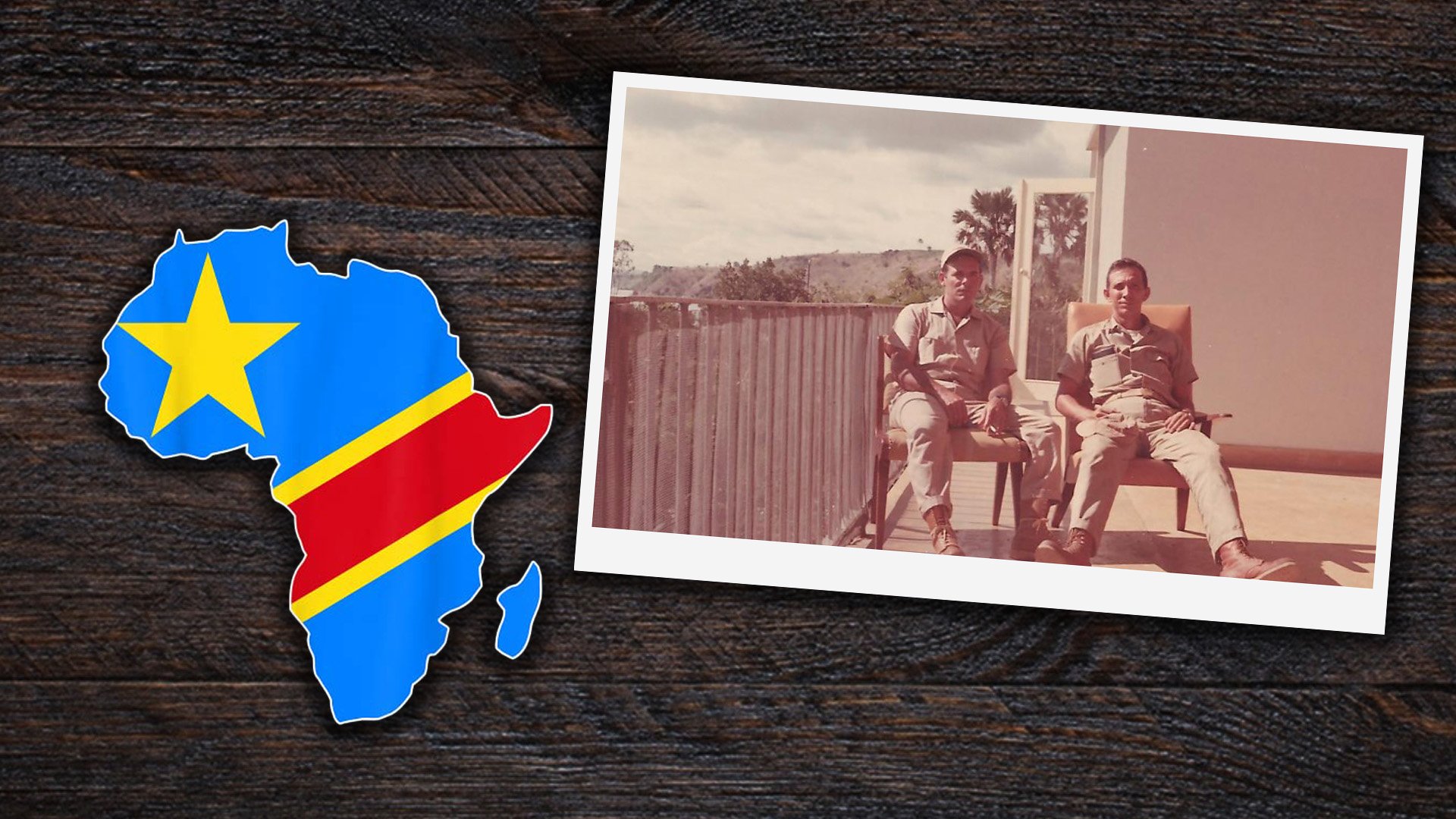

Roberto Pichardo, right, was recruited by the CIA for a covert operation in the Congo in Africa in 1965. Photo courtesy of Manny Pichardo. Composite by Coffee or Die Magazine.

On April 15, 1961, the operation got underway. Eight B-26 bombers disguised as Cuban aircraft took off from Nicaragua en route to Cuba. The bombers reached their objectives but failed to strike several key targets, leaving Castro’s air force largely intact. When international news outlets reported on the bombings, showing imagery of the poorly disguised B-26s in Cuban airspace, America’s involvement in the attack became apparent. At that point, Kennedy called off the second bombing raid. And yet the mission continued.

The following night, April 16, some 1,400 Brigade 2506 raiders, including Pichardo, embarked from the northeast coast of Nicaragua aboard five large troop transport ships and numerous landing craft. Another vessel, called Blagar, carried the CIA officer and five UDT commandos. They were supposed to complete their voyage before sunrise, but as the fleet advanced across the Caribbean, word came down that CIA analysts had indeed misinterpreted the U-2 surveillance imagery. As some of the brigadistas had already pointed out, the “seaweed” identified in the photographs was in fact a coral reef. The assault was halted and did not resume until daybreak.

When the fleet finally entered the Bay of Pigs, the frogmen boarded inflatable rafts and paddled to Playa Larga ahead of the main invasion force. The frogmen were to conduct a reconnaissance of the area to help guide the landing craft to shore. Upon reaching the beach, however, the commandos were promptly discovered by a group of local militiamen. A firefight ensued, and the militia radioed Cuban military forces to inform them of the landings. Meanwhile, Pichardo was aboard a small landing craft motoring toward Playa Girón. About 100 meters from shore, the vessel struck the coral reef and the coxswain released the ramp, telling the assaulters that they would have to swim the rest of the way. Waves splashed the men inside. Some fell into the water and were dragged down by their gear. Seeing a shorter teammate vanish under the waves, Pichardo leapt from the watercraft and dragged the man onto the ramp by his backstrap. Then he reentered the water and swam the remaining distance to the beach.

Cuban exiles recruited by the CIA, on board one of two Swift boats in their arsenal in 1965, played a large role in Che Guevara’s downfall in the Congo. Photo by Roberto Pichardo, courtesy of Manny Pichardo.

Over the next three days, Pichardo and his comrades hunkered down at the airfield and awaited guidance. Castro retaliated with airstrikes on Playa Larga and Playa Girón. Pichardo and his comrades, including radioman Roberto García, were caught completely off guard when T-33s and B-26s appeared overhead and began strafing their positions. Pichardo and García watched a friendly B-26 bomber get shot out of the sky, and the pair ran to the wreckage. The aircraft was on fire and the pilot, Matías Farías, was trapped in the cockpit. Pichardo and García pulled the emergency handle to remove the canopy, then extracted Farías and dragged him to cover. On the morning of the 19th, a C-46 made a surprise landing on the runway, and Farías, who had suffered minor burns, received the last ticket out of the Bay of Pigs.

As time passed and Castro’s troops moved closer, it became clear to Pichardo that help wasn’t on the way. Survival being the only goal now, he decided to join a group of his comrades who were planning to escape by sea. According to Pichardo’s son, Manny, he returned to the beach, where he and another brigadista fashioned a makeshift raft from driftwood and then paddled out into the bay. For the next two days, they floated offshore until they reached the keys surrounding the Bay of Pigs. All the while, Cuban forces patrolled the area in boats.

Pichardo was hiding in a grove of trees when he heard men calling him out by name. It was Castro’s soldiers, who had learned of Pichardo’s whereabouts from some of the captured brigadistas. They were urging him to surrender. He and García decided then to give up. They emerged from the trees with their hands up and were taken prisoner. Their comrades who refused to stop fighting were hunted down and shot.

In total, more than 100 Brigade 2506 soldiers were killed over the course of the operation. Approximately 1,200 were taken prisoner. Many, including Pichardo, ended up in Castillo del Príncipe, an 18th-century Spanish fortress in Havana that had been converted into a prison. Placed in large, hundred-person cells, they remained there for about 20 months until the Kennedy administration finally negotiated their release in exchange for medicine and money.

President John F. Kennedy honors members of Brigade 2506, including Roberto Pichardo, at the Orange Bowl in Miami, Florida, on Dec. 29, 1962. Photo by Cecil Stoughton/White House Photographs.

Pichardo arrived back in Miami on Christmas Day 1962, nearly two years after he had left his wife and children to fight for the liberation of their homeland. Just four days later, Pichardo and his Brigade 2506 brethren were honored by Kennedy at the Orange Bowl in Miami. Holding the unit’s blue-and-yellow guidon, Kennedy promised the 2506 veterans that they would one day return to a free Cuba — a promise he certainly attempted to make good on but never fulfilled.

The failed Bay of Pigs invasion was one of several attempts by Washington to infiltrate the coastlines of Cuba and ignite an armed revolt against Castro. Between 1963 and 1964, Pichardo and a number of other 2506 veterans were recruited once again by the CIA for the so-called Cuban Project, better known as Operation Mongoose. The operation was called off before Pichardo completed his training, but his fight against communism didn’t stop there. In 1965, as the CIA’s focus shifted toward battling communist revolutionaries in Africa, the agency hand-picked Pichardo to join a team of Navy SEALs, Cajun boaters, and fellow Brigade 2506 veterans for a mission to hunt down rebels operating in the vicinity of Lake Tanganyika. In a matter of months, the team not only discovered that Che Guevara was leading a guerrilla army in the Congo but also forced the famous revolutionary to abandon his communist mission in Africa altogether. Guevara later recounted this experience in his diary as a “story of failure.”

After Africa, Pichardo retired with his family in Miami and became a US citizen. In September 2020, then-President Donald Trump quietly honored Brigade 2506 veterans at the White House. Pichardo, among the last of the unit’s surviving members, attended the ceremony dressed in a navy blue suit. Inside the Oval Office, the small group presented Trump with a blue-and-yellow flag similar to the one they had given Kennedy some 58 years earlier. As Pichardo gathered by Trump’s presidential desk for a group picture commemorating the special occasion, he glanced down to the ring on his finger, once worn by his brother-in-arms Roberto García, who died in 2018. García had given the ring to Pichardo four days before he passed, asking that he wear it in his memory and to serve as a reminder that their story wasn’t over.

In May 2022, the 86-year-old Pichardo suffered a stroke. It is unlikely that he will ever see his native Cuba transformed into a democracy. Still, he believes that the men of Brigade 2506 did not fight and die in vain. As he sees it, their sacrifices represent the true cost of freedom and should be remembered as such by all Americans. Asked what he considered his proudest accomplishment, Pichardo was unequivocal in his reply: “Trying to liberate Cuba from communism.”

This article first appeared in the Fall 2022 print edition of Coffee or Die Magazine as "Inside the Bay of Pigs."

Read Next: Operation Mongoose: Exploding Seashells and Other Crazy Ways the CIA Considered Killing Fidel Castro

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.