“The Bridge on the River Kwai” won Best Picture and six other Oscar nods from the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences at the 1958 Academy Awards. What the film did not win was the respect and admiration from members of the Far East Prisoners of War (FEPOW) due to the fictitious portrayal of events. One FEPOW member, John Coast, a young British officer who experienced three and a half years along what later became known as the “Death Railway” had harsher words than those from Hollywood. “‘The Bridge on the River Kwai’ (BBC1) was the season’s Distinguished Film,” he said in a clipping sent to Laura Rosenberg in 1974. “As nobody should ever have need telling, the picture is a load of high-toned codswallop.”

Unlike Freddy Spencer Chapman and members from the Special Operations Executive (SOE) who conducted sabotage and irregular warfare operations in the jungle against the Japanese after the fall of Singapore in 1942, Coast — among 61,809 Allied (British, Dutch, Australian, and a small contingent of American) troops and 200,000 rômusha — suffered immensely under the 12,000 Japanese and 800 Korean captors. The Japanese discovered abandoned British plans from the 1880s that estimated the Burma-Thailand railroad could be built in five years and, because of pressures to finish the bridge and the loss of momentum during World War II, the railroad became a priority to complete in a fraction of that, no matter the cost.

Their new prisoners of war (POW) became their cheap labor force; thousands perished and few lived to tell the real story.

Before Building The Railroad of Death

Coast’s 1969 BBC documentary “Return to the River Kwai” detailed the necessity for a supply route despite the impossible task to build it: “When Japan entered the war, Malaya and Burma fell an easy prey to her armies, and the road to India lay open. The sea route was too vulnerable, so the Japanese High Command in Tokyo ordered the railway, which then ran only 50 miles West of Bangkok, to be extended another 250 miles up through the jungle to Burma.” The railway would allow the Japanese to regain momentum after losing naval strength on the sea and attack the British by ground from India to spread their control from Southeast Asia toward Europe.

To increase efficiency under the guidance of Japanese engineers — whom the 1958 film falsely portrayed as incompetent — camps were spread out to cut through the jungles all along the 415-kilometer, or 257-mile, route connecting Thanbyuzayat, Burma (now Myanmar), with Non Pladuk, Thailand.

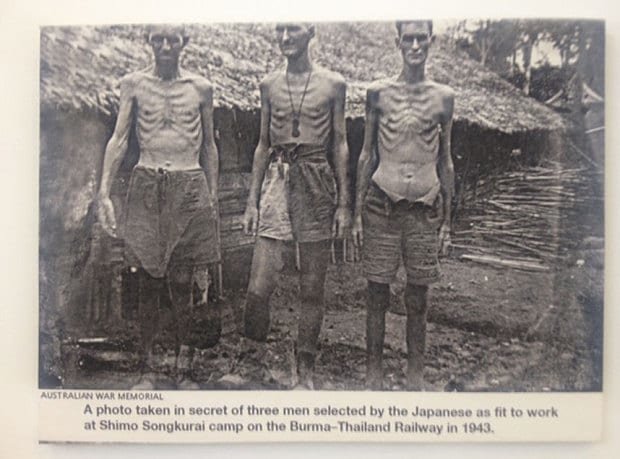

While held in Singapore awaiting transport to the railway, the condition of the POWs was deteriorating fast. Once athletic and able, the soldiers’ muscle tone evaporated and their rib cages protruded from their skin like walking skeletons. Running on a diet of rice for breakfast, soupy rice for lunch, and occasionally old cow meat and fish guts topped with maggots and rice for dinner, it didn’t exactly replenish their energy. Several suffered from dysentery, which further dehydrated their bodies, and struggled to manage their delicate immune systems.

The Japanese soldiers were acting on orders, and several decades after the war, many plead for forgiveness for what was to come. The POWs were packed like sardines while traveling from Singapore to Thailand — some 40 men to a single 5.5 meter by 2.5 meter railroad car. Very little food — not more than a few mouthfuls of rice — was supplied for their five-day journey. A pint of water a day was often shared amongst the men, who rationed it in sips. Those who drank contaminated water were subjected to cholera, which was rampant in their decline.

The POWs who traveled to Burma, however, faced their own horrors aboard “hell ships,” where 15,000 POWs died during World War II because none of the belligerents — despite urgent requests from the International Committee of the Red Cross — marked their ships, resulting in their own side’s submarines attacking and sinking indiscriminately.

In addition, the cargo ships were old, dirty, and lacked ventilation and life-saving equipment. Roy Whitecross, a POW headed to Japan instead of the railroad, remembered his experience when U.S. submarines attacked his vessel. “In the hold there was a silence and a deep calm,” he recalled. “No man deluded himself about his chances of escaping if a torpedo struck the ship. Five hundred men and one steel door, which would have to be opened anyway … So this was it. No fuss, no shouting. Just quiet resignation.”

The POWs who traveled to Burma, however, faced their own horrors aboard “hell ships,” where 15,000 POWs died during World War II …

In the documentary “Building Burma’s Death Railway: Moving Half the Mountain,” Jack Chalker, a member of the British Army Royal Artillery, described how they used humor to cope with the everyday stresses at their first prison camp before heading to the railway. “They would point to your shoes and say ‘namae ga,’ meaning ‘what is the name of it,’ so we would say ‘shit,’” Chalker said. And then they’d watch the Japanese soldiers go around pointing to other people’s good boots to compliment them. “It was hilarious because we had a lot of fun for about two weeks then they suddenly got the message from the Japanese interpreter, then we had to learn Japanese orders.”

Smiles were few and far between but were replaced with agony after arriving at the railroad.

The thought of escaping into surrounding nations was suicide. Coast writes in his now-revised 1946 book “Railroad of Death,” the original account of the River Kwai railway, that because of how the Japanese patrolled the sea, their planes were alone to roam the skies. India and Australia were the only possibilities; however, Australia is 2,000 miles away by boat, and India is the same distance but through dense jungles. Malnutrition and disease added to their despair.

“Then you should reach the Thai border, you have another people to cope with, another language, hundreds more miles of jungle, tens of thousands of Nip [sic] troops, and still have all Burma before you!” Coast wrote. “No, escape was lunacy.”

Death March to Hellfire Pass

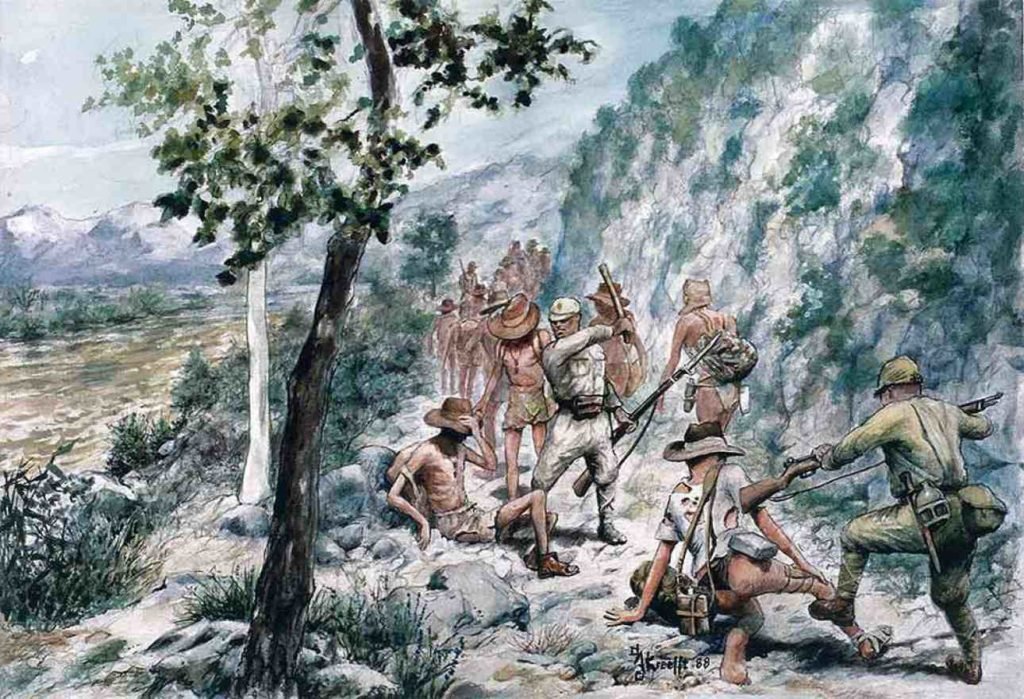

The Bridge on the River Kwai, commonly referred to as the Railroad of Death or Death Railway, which stands in Kanchanaburi, Thailand, was one of only eight steel bridges of the estimated 688 that were built. The rest were made of wood and local materials. The Japanese Railway Regiment forced thousands of allied POWs and natives to build the railway using what they could carry in their hands or on their backs from nearby camps. The barbaric methods without modern mechanical technology subjected each man to find their soul to survive.

Standing in front of a dense wall of jungle, miles of uneven terrain, mountains that needed to be blown apart with explosives and armed with just hand tools, working 18 hour shifts — the Japanese felt no sympathy as they poked at the prisoners with bayonets when they struggled to continue. They used outdated equipment, such as an 8- to 10-pound hammer and tap, carried supplies up and down uneven rock surfaces, faced fears of heights while standing next to cliff faces, and overcame the dangers of working around the clock despite illness and fatigue.

While constructing the Wampo Viaduct, a series of trestle bridges that runs along the river Kwai, A.E. Field and L.J. Robinson said, “Standing precariously on the sill, you swing your hammer and the whole trestle shook, especially nerve wracking doing it in the dark with only fire light to see with.” Their tireless work built this difficult section in 17 days.

“The place earned the title of Hellfire Pass, for it looked, and was, like a living image of hell itself.”

Elephants walked alongside, aiding in moving equipment and using their trunks to carry out felled trees. Some stems of bamboo took five or six men to extract from the earth, and the exhaustive work had great consequence. The worst aspect of bamboo clearing was avoiding the prickly thorns that were sharp enough to impale the skin. Some wouldn’t even feel the pain until a small jungle ulcer formed in their leg, which could grow to the size of a baseball. It would often need to be amputated. The ever-present sun caused heat stroke and didn’t relent until monsoon season crept in.

Although the rain was an initial relief, it didn’t soften beyond a pour for 140 days. They worked, ate, and slept on tiny bamboo mats without blankets or cover as their skin rubbed raw. Malaria-carrying mosquito populations exploded.

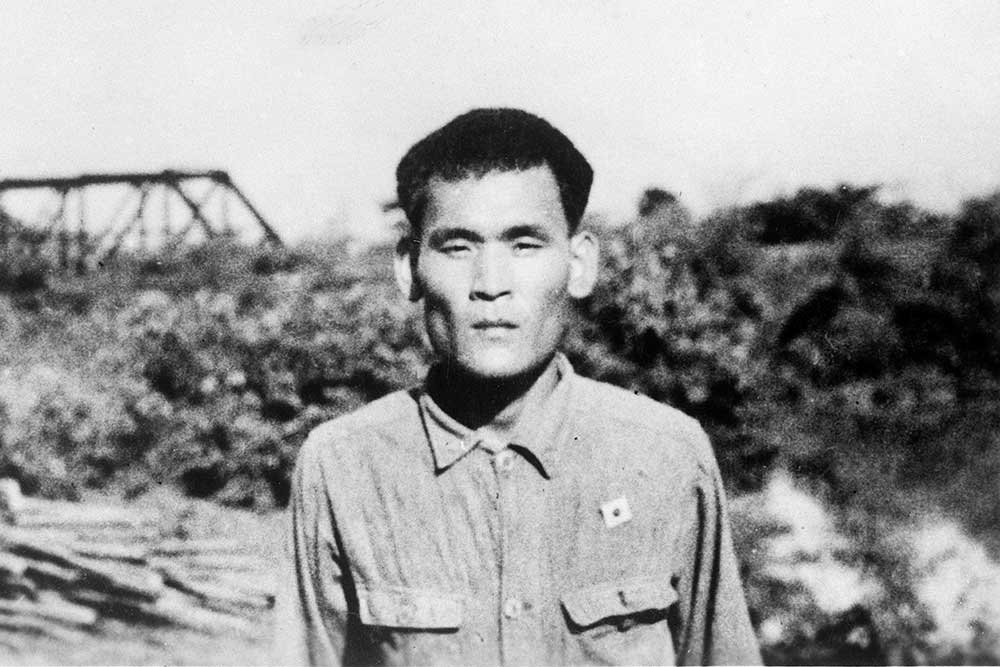

“The hardest thing was the rain — there was so much of it. The bridge was demolished by rain; these were terrible conditions to work in as I recall,” said Yoshiro Kurimata from the Railway Regiment.

“We knew now that solid jungle or forest lay before us and that what we’d had so far had been easy,” Coast said. “Some parties of sick men from Singapore, totally unused to our conditions, were doing forced marches 20 kilometers a day heading straight to the Burma border.”

To build embankments, baskets of dirt and rock were carried largely from the rômusha (Malays, Chinese, Tamils, and Java) — who enlisted to work on the railway because they were promised a better life, which turned out to be a lie. One method to increase efficiency was to use a tanka, one pole of bamboo carried on the shoulders of two men while buckets hung on either side. This method had its limits because the monsoons made the soil run with water and mud, which caused slippery surfaces.

The most horrifying section of the railroad took its toll on hundreds of Australian POWs and had an infamous reputation. “The place earned the title of Hellfire Pass, for it looked, and was, like a living image of hell itself,” Jack Chalker said.

At one camp, upwards of 120 leg amputations were performed as a result of jungle ulcers — without even so much as an aspirin for the pain.

The unpleasant conditions worsened when the Japanese issued a “Speedo” from April to August 1943 to ensure the railroad would be complete and they’d have a chance in winning the war. This expedited the work to ensure that the average 1 meter of cutting per day was expanded to 2 to 3 meters. Hellfire Pass was cut 75 meters long and 25 meters deep; at that pace, many died where they stood the previous day. It was later determined that for every railroad sleeper laid, one POW died.

A piece of Hellfire Pass that spanned 3.5 kilometers was dubbed the “Pack of Cards Bridge” for its unwillingness to stand upright. It fell on three separate occasions, killing the morale, angering the Japanese, and ending the bloody progress they worked so hard to achieve.

Punishment

If a prisoner refused to obey, he would be smacked across the face or beaten, most likely by an officer to discourage others from doing the same. Other punishments included being forced to hold large boulders over their heads until their arms failed or erecting sweat boxes where a person couldn’t lay down or sit properly.

“I no longer remember much other than the pain, then I was put in the black hole. That was probably the one time when I felt this was the end,” Alistar Urqhart recalled of the sweat boxes.

Sergeant Seiichi Okada, known as “Doctor Death,” worked in the Hintock-Konyu-area near Hellfire Pass as a medical officer and was notorious for sending POWs on their deathbeds out to work despite their failing health. Under the Geneva Convention, such treatment of prisoners was not allowed, but since the Japanese didn’t sign the treaty, they didn’t abide by the rules.

A Korean guard named Arai Koei was nicknamed “The Mad Mongrel” for brutally beating POWs, sometimes using shovels and bamboo to exercise his point. The relentless work of the POWs was never rewarded with rest, only punished with force.

Dunlop’s Thousand

Despite all the suffering and death, there was a small sliver of hope that they would make it out alive. This can be largely attributed to Sir Edward “Weary” Dunlop, an Australian medical officer who worked as a physician providing aid to more than 1,000 POWs. His nickname was ascribed to his resiliency to “never wear out,” and those he helped were known as the “Dunlop Force” or “Dunlop’s Thousand.” In March 1943, he moved to Hintock Mountain Camp, which was the northernmost camp near Hellfire Pass.

“The British originally had it planned to build in five years, yet we completed it in one and a half years. So we really had no time to think about the human cost.”

Dunlop used his expertise to heal the POWs’ injuries from beatings and the wilderness. Rowley Richards from A Force wrote, “He managed to pinch some scrap steel out of the Railway and made me an excellent instrument which I used daily. Among so many men in camp we had access to qualified experts in a wide range of fields, and all of us became skilled at the art of improvisation.”

At one camp, upwards of 120 leg amputations were performed as a result of jungle ulcers — without even so much as an aspirin for the pain. A member of the “Dunlop’s Thousand,” 21-year-old Billy Griffiths, was forced by the Japanese to uncover a camouflaged and booby-trapped ammunition dump, which caused a blast that took his sight and his hands. The Japanese left him for dead, but Dunlop cared for him until the end of the war. Griffiths’ recovery was remarkable, and he went on to become “Mr. Disabled Sportsman of the Year,” living a life of national inspiration despite his injuries.

Some locals were sympathetic to allied POWs and risked it all to bring aid. Boon Pong Sirivejjabhandu sacrificed a successful business and prosperity for several years. Boon Pong was a Thai merchant who used his contract with the Imperial Japanese Army to smuggle medicine and radio batteries to sick and dying POWs, mostly in tandem with Dunlop. His contract allowed him to enter the camp under little management. If caught, he would have met the wrath of the Japanese who entrusted him to carry out their orders.

Aftermath

The railway was completed on Oct. 16, 1943. “The British originally had it planned to build in five years, yet we completed it in one and a half years. So we really had no time to think about the human cost. We followed orders without thinking of sacrifice,” said the Railway Regiment’s Takeo Yoshino in a documentary.

The conclusion of World War II moved resources to recover the fallen — an estimated 12,800 Allied troops, and more than 90,000 of the 200,000 rômusha who died while working along the railroad were found in unmarked graves. After consulting with members from the Japanese Railway Regiment who had surrendered, 10,549 graves and 144 makeshift cemeteries were discovered. The POWs told the liberators where to find their buried documents, records, and journals of the atrocities, which they had hidden from the Japanese. These provided firsthand accounts that would serve to prosecute Japanese commanders for war crimes.

The Mad Mongrel was sentenced to death by hanging. The Australian government carried out death sentences by firing squad of those who were tried for crimes against humanity. As many as 5,739 Japanese, 173 Formosans, and 148 Koreans were tried; 984 were sentenced to death, 475 received life sentences, and 2,944 had reduced sentences for their involvement. In addition, high-ranking Japanese officials and officers were tried in the International Military Tribunal of the Far East between 1945 and 1951.

Today, several memorials and commemorations can be found along the route of the Burma-Thailand Railroad. Some of it remains as it was originally built, while other sections have been refurbished to remember and honor the sacrifice of so many lives.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.