Robert Young Pelton — The Adventurer, Journalist, Author Who Introduced Us To ‘The American Taliban’

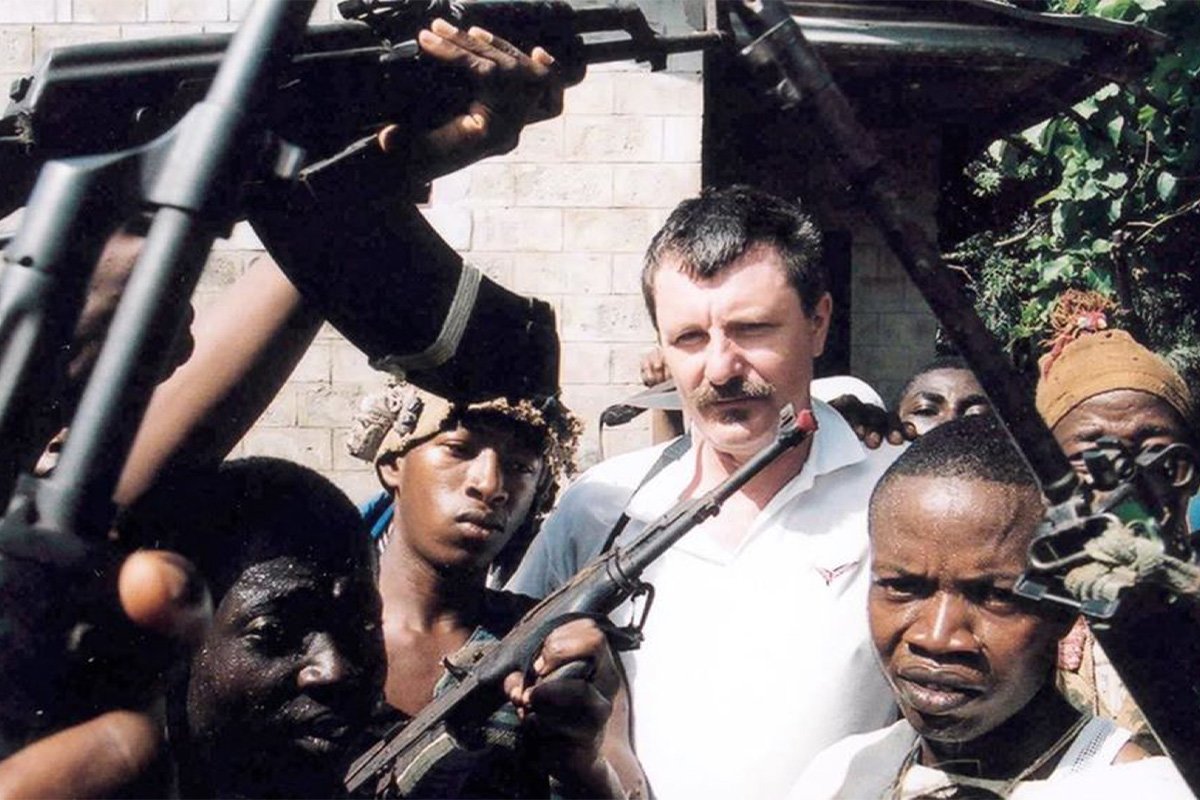

In Sierra Leone. Courtesy of Robert Young Pelton’s Instagram.

On Dec. 1, 2002, author, adventurer, and journalist Robert Young Pelton was in a place he had been many times before: Afghanistan. He was standing over a wounded foreign fighter in a makeshift hospital in the aftermath of the Qala-i-Jangi Fortress prison uprising.

Years earlier he owned a company that provided product development and marketing services. That company, Pelton Associates, was ranked 145 on the INC 500 List. Even with this level of success, Pelton felt he was spending most of his time making other people happy at the expense of his own happiness. After the death of his father and several of his mentors, Pelton decided that the one month of expeditions that he set aside for himself each year was no longer enough. In mid-1990, at the age of forty, Pelton flipped the script and exchanged expeditions for full-time travel to war zones.

“Was your goal to become Shaheed or Martyred?” Pelton asked while conducting an exclusive interview for CNN. “It is the goal of every Muslim,” replied John Walker Lindh, an American from Marin County, California.

From that moment on, John Walker Lindh was mislabeled “The American Taliban,” but in reality, according to Pelton, he was part of the Arabic-speaking 055 Brigade, trained and funded by Usama bin Laden.

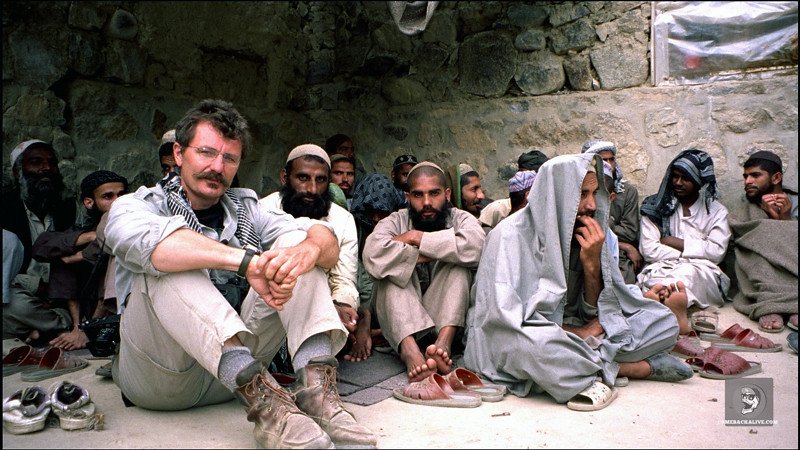

Words like “Shaheed,” “Martyr,” “Taliban,” and “Al Qaeda” were new and confusing to many in the media, but they were all too familiar to Pelton. Pelton had been traveling to Afghanistan, Chechnya, Algeria, and other hot spots for years. Researching, embedding, and spending time on the ground trying to understand these groups and the risks they pose for his book, “The World’s Most Dangerous Places.” Pelton provided a perspective of dangerous places that was not from behind embassy walls, and not from the relative safety of an airport or a hotel rooftop. Pelton linked up with warlords, rebels, and militants and captured stories on the front lines, in the mountains, and in cities under siege where few Westerners dared travel.

COD: On the talk show “Coast to Coast,” you compared ISIS to the mob. You explained how they moved into an area where the populace had a grievance. They bring in trainers and take control of local businesses and then start taxing people. I’m having visions of drop the gun, take the falafel. Am I right?

RYP: [Laughter] You have to remember nothing is new; it’s based on traditional concepts. We were taken aback by Al Qaeda and terrorism because we didn’t take them seriously. Before 9/11, the general description of a terrorist was a white guy who had been trained by the U.S. Army and wanted to blow up federal facilities. So, we weren’t looking for Arabs or Saudis — they weren’t on our radar.

As you mentioned, these groups look for an area that has a grievance — there’s a lot of tribal and religious problems out there. So, they go in and sit down with the weaker or smaller group and say, if you pledge Bayat, or if you pledge to support ISIS, we’ll bring in money, training, PR guys, etc. And the people say, “As long as you kick the other guy’s ass, we’re in for this.” They then go house to house or business to business, and the people have to kick up 10 or 15 percent. Once paid, they have a stencil that they paint on your wall to let others know you paid your taxes.

Then every week they bring out some poor bastard that didn’t pay or they don’t like and they chop his hand off or his head off or whatever and then the people realize, they’re actually causing them problems because here comes the Americans and they’re going to bomb the shit out of us. Then the people become human shields.

COD: You were at the Battle of Grozny. How were you able to establish safe passage with the Chechen Rebels on one side and the Russians on the other?

RYP: Basically, there were two wars [in Chechnya]. At the first one, in 1994 to 1995, journalists had access.

In the second war, in 1999, Russia’s goal was just to murder or kidnap [journalists]. So, it was difficult. I went in with the rebels, which is even more difficult because rebels aren’t just one unit.

I met with other groups, too, like the Turkish Mafia and the Chechen Mafia, to tell them this is what I am doing, don’t kill me. The funniest meeting was with bin Laden’s people in London, in a bookstore. They said, “We know who you are. Eighty percent of what you write is true.” I said, “Fuck you, 100 percent.” They said, no, 80 percent is better than the rest.

The point being, you had to get permission. The Chechens in Istanbul, these guys that wear these leather jackets and tall lambskin hats, they came storming into this room. They said, “We understand you want to go into Grozny … you understand it is dangerous?” I said yes. “You understand you might be killed?” I said yes.

They said, “If you agree to these terms, my men promise you one thing: you will not be killed until the last of my men are dead.”

It was serious stuff, we were under attack all the time — all kinds of espionage, people getting kidnapped. There was one journalist that went in at the same time I did; he got kidnapped, handcuffed to a radiator, and then eventually went back home and blew his brains out.

COD: While in Grozny, you met a young American who was fighting for the rebels. He went by the name Aqil. Can you tell me about him?

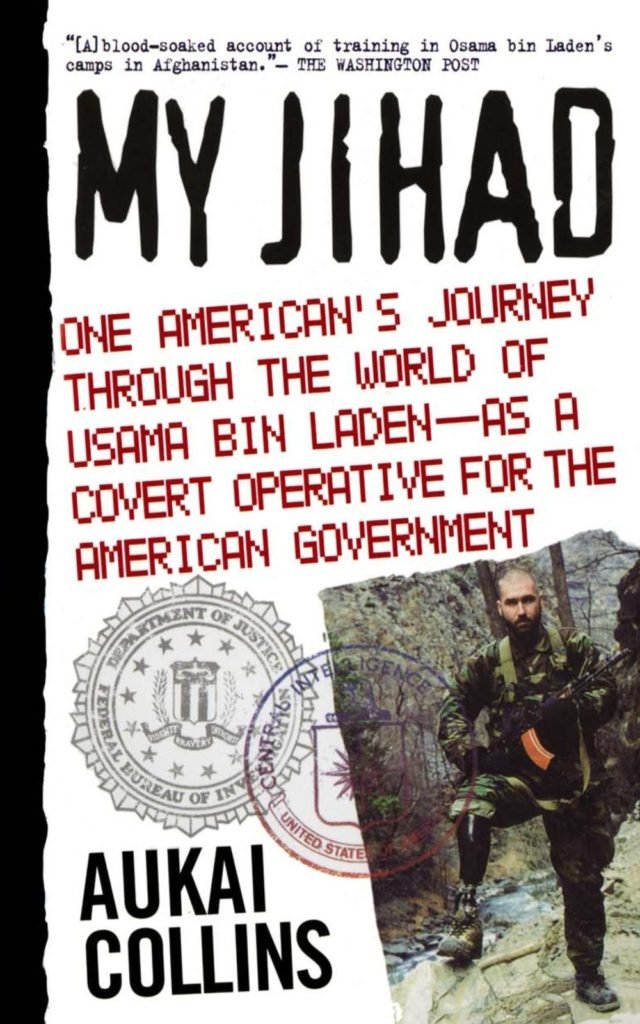

RYP: His name was Aukai Collins, he was Hawaiian, called himself Aqil. He had been given my book by one of his handlers. He wanted to go back in and fight; he had been trained in bin Laden’s camp. His wife was inside Grozny. He asked if I could get his wife out, I said sure.

[Sigh] He wanted to go in and die. Of course, they all talk tough … He was a blue-eyed, red-haired guy. He actually offered to kill bin Laden by going back to the training camps and dealing with him directly. He was a psycho killer. He liked to kill people. He lost one leg the last time he was there. He was in the ’94 war with the Jihadis, what we would call Al Qaeda.

The first day we went in we had to flee the canyon we were in before it got bombed. Then Aqil just vanished. He took off in a car to the front line, and I ended up walking around with his spare leg hanging out of my backpack for a week. I thought that was pretty funny.

We met up again in Grozny on the front lines. I thought he had been killed. When I got home, I was writing the story. I was literally writing the part about how they told me he had died. Next thing, the phone rings, and it’s him like, “Hey dude, what’s up?” And I was like, you ruined my whole story. He ended up on heroin. He had anger management problems. He eventually died of sepsis. He had six or seven kids, all around the world with different wives.

I went to visit him in jail in Mexico — I don’t think he was meant to live that long anyway.

COD: Why was he in a Mexican jail?

RYP: He foolishly went down to Mexico as a bounty hunter and got rolled up by the Mexican police for two serious crimes. One is having weapons, the second is kidnapping people. I basically told him, “I want nothing to do with you.”

COD: Did you help him write his book, “My Jihad”?

RYP: I don’t support what he does, but I said that this is a chance for America and the world to read about how people go from being, you know, a red-headed kid to being trained in Usama bin Laden’s camp. You’ve got to remember, I met him before the John Walker Lindh interview. So, I got him a book deal. The premise, I told him, is very simple: tell the truth. It’s a pretty good book. I think anyone that reads that will be blown away at how easy it is to radicalize Americans.

COD: In 1993, his journey to Islam led him to a mosque in East San Diego. Within four short months — against the advice of the members of the mosque — he became consumed with the idea of jihad because of the fighting in Bosnia. Do you think that’s common, that a young male convert would skip over most of the pillars of Islam and land on what is arguably the sixth pillar, jihad?

RYP: Let me say something that’s really important because I’ve known hundreds of jihadis — it’s a cult. It’s got nothing to do with Islam. I’ve never seen Aqil pray. Not once. I never saw him discuss Islam. Never seen him engaged with any kind of religious activity.

He scammed his mosque to give him five grand — he went out and bought a backpack and some new boots. They’re people that are missing something mentally. These people want to kill people. They’re no different than school shooters. When they hear, “Let’s go fight jihad, let’s kill people,” that appeals to them. It’s got nothing to do with religion.

They’re sociopaths, psychopaths. If some guy from the mob said, “You want to be an enforcer, I’ll give you a gun, you can blow people’s brains out, or you want to work for the cartels, I’ll give you an AK and an SUV” — he would’ve taken that job. Go inside these groups and they believe things almost like Scientology. Bizarre things. Things that make no sense — make perfect sense to them, like when you die you will smell like flowers. You will be smiling. All of these beautiful things. It’s like dude, no, you’re just cannon fodder. Logic disappears.

Now with Syria and all of the foreign fighters, the question is can they can be rehabilitated? And I don’t know if you can. Unless we fully admit that this has got nothing to do with religion. It is a personality defect, and I’m not talking about people defending their homeland. I’m not talking about a guy who feels oppressed and decides to join against a government that killed his father or whatever.

“Let me say something that’s really important because I’ve known hundreds of jihadis — it’s a cult. It’s got nothing to do with Islam.”

COD: Looking at some of your other projects, you own Somalia Report. What does that entail?

RYP: I did my thing as the world’s most dangerous guy, and I was in the media all the time and I said, “This is great, but it’s kind of bullshit, this is not really connecting the dots.” I noticed every time there was a war, CNN and ABC would spend millions of dollars sending some untrained guys to go into a war zone and then hire stringers to give 15 seconds of what they thought the news was about. It dawned on me that this huge exercise cost millions of dollars and I could create a huge network of those same fixers — you know, the people that were connected and smart.

So, the first time I did that was in Iraq — I called it “Iraq Slogger,” and it did very well. We had villagers and people all around Iraq just telling us what was going on. Then we moved to Afghanistan for a year and a half, and then the Agency found out and I ended up on the front page of The New York Times as a ninja assassin.

Then I got pissed off and went to Somalia to track all of the hostages and all the ships that had been captured because no one was doing that. That’s where I set up a ground network called “Somalia Report.” Again, you have to remember, there was no reporting coming from there. We started creating news and real coverage. I set up networks in Libya, Myanmar, and Bangladesh. It’s the new way to do news.

COD: Is this a big difference between the journalism model we use in war zones now?

RYP: Well, we have hotel journalism. They typically want you to report every night. So, say you’re in Iraq — they literally stay in a luxury hotel and go up to the roof every night to do their piece. It means you have one day to come up with a story, so you are using stringers or you just go with whatever is fed to you. It discourages real, deep investigative journalism. What you’re seeing is a bunch of good-looking people standing with the background of a city telling you what’s going on.

To be fair, people don’t want to see dead people and dead babies every day, or wounded troops screaming. Can you imagine if we had more coverage of Yemen right now? We would get out of that war immediately. We allow wars to go on because we don’t see them.

COD: You’re not on Facebook anymore. At one point, you were trying to upset people in order to have them unfriend you so you could give out some of those slots.

RYP: Yeah, I would call it Thunder Dome. Just make people so outraged that they would unfriend me — “unfriend me,” ooh.

There was a piece about how Facebook broke the law during the election — so I posted that. Then underneath it I said, “But that’s not the bad part.” I said, “Here is how people use Facebook to kill people.” I went into great detail about how my friends use social media to track down and kill people. Now, I’m talking about terrorists. Within 15 minutes, my whole site, everything was gone, and then my Instagram site — poof — was gone. Then I got an email from some generic person saying that I violated their policy. I wrote back asking which policy, and they wrote back and said I was advocating violence. And I’m like really? Because I don’t advocate violence. I realized that I had touched a nerve.

I do try to tell people that if I were to hunt down people, I would use Facebook. For example, right now I am tracking people that left Libya on Facebook and LinkedIn, and it’s like tink, tink, tink. It’s an extremely dangerous tool.

COD: Great intelligence tool. If you remember a while back, when John McAfee was on the run, a journalist posted a picture of him somewhere and forgot to remove the metadata, and that’s how officials tracked him down.

RYP: Okay, that was posted by my good friend Rocco Castoro. He sent it to Vice, which is basically child journalism. He told them, “Hey — make sure you remove the metadata.” Which you normally do by making a GIF or something. So, the child-journalists back in Brooklyn didn’t bother to do that and that is how they found his location. McAfee is probably the least secretive guy on earth because he keeps telling people where he is.

“I do try to tell people that if I were to hunt down people, I would use Facebook. For example, right now I am tracking people that left Libya on Facebook and LinkedIn […] . It’s an extremely dangerous tool.”

COD: Are you still using the Huawei Phone for photography?

RYP: Yeah, it’s a great phone, and I want to get the new one, the P30 Pro. I’ve spent tens of thousands of dollars on cameras, but that little phone, the P10 Pro, takes spectacular pictures. I can also use it as a burner phone overseas. The point is: it takes beautiful pictures and you can throw it in your pocket. If I whip out one of my Leicas, and I start taking pictures of some troops, and they don’t like it — they’ll come over and smash my $10,000 Leica and my $4,000 lens. If I pull out a phone, it’s actually more normal.

It’s a less hostile tool to take pictures with, and I can instantly send them. The thing I like about Huawei is it has a little Micro SD. So, if I take a lot of pictures and I want to take them out of the country and not go online, the card can go somewhere on my person and they’ll never find it. The worst thing that ever happened was not being able to take the battery out of your phone. The tracking device on your phone is a great tool for any in-country intelligence operation, and when you’re coming back to the airport, they can get everything off your phone.

COD: Do you have anything else you would like to add?

RYP: I just want to say, we grow up in society really quickly, without those classic transition points that society is supposed to give you. We go from being a child to a teenager, and suddenly we’re an adult — and we forget there is a certain window in human life that’s critical to the transition period from boy to man and girl to woman.

We need to bring that back. The British call it the “gap year.” I don’t know what it’s called in America because you just start working. We need to just let people experience people and life, and different places and cultures so they’re not so terrified when they come back. That’s a critical part of society that we are missing.

Life is an adventure and risk is good.

David Bruce is a retired federal law enforcement officer. Throughout his career, he served mostly in counterterrorism roles and tactical instructor positions. As a task force officer for the Boston Joint Terrorism Task Force (JTTF), he spent more than five years investigating domestic and international terrorism cases. Prior to his assignment on the JTTF, he served as the lead instructor for the Boston Office of the Federal Air Marshal Service teaching anti-hijacking tactics, firearms, and tactical surveillance. In 2019, David graduated from UMass Amherst with a degree in journalism. Before embarking on a 25-year career in law enforcement, he served in the US Army as a paratrooper/combat medic in the 82nd Airborne Division.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.