Do you remember Rosie? She was a young woman in her mid-20s when the U.S. was pulled into World War II in 1941. The iconic poster of her flexing her bicep and clenching her fist has captured the imagination of millions of patriots for more than 75 years. It has adorned every type of novelty item imaginable, and people have even tattooed her likeness onto their body.

Rosie represents the strength and resilience of the Greatest Generation’s women — a generation slowly fading into the sunset.

The iconic, stylized poster many associate with Rosie the Riveter was created by J. Howard Miller for Westinghouse Electric’s internal War Production Coordinating Committee. The original intent of the poster was to boost morale among Westinghouse workers and encourage them to work harder. In truth, only 1,800 copies of the 11×22-inch poster were printed — they were displayed for no more than two weeks and never outside the company’s walls.

The Westinghouse factories that posted the artwork were primarily responsible for making a proprietary material called Micarta, which was used for manufacturing helmet liners. Ed Reis, a volunteer historian for Westinghouse, confirmed that Miller’s illustration was never shown to female riveters during the war. He joked that the woman pictured was more likely to have been named “Molly the Micarta Molder” than “Rosie the Riveter.”

It was not until decades later in 1982 that the “We Can Do It!” poster would resurface in a collection of artwork published in the Washington Post Magazine. Since then, the image has been re-appropriated to promote many causes, from the empowerment of women to postage stamps and political campaigns for the likes of Sarah Palin, Ron Paul, and Hillary Clinton.

Exactly who provided the inspiration for Miller’s illustration is the source of a long-standing debate. In 1994, a Michigan woman named Geraldine Hoff Doyle — then 70 years old — saw the “We Can Do It!” poster for the first time when it appeared on the cover of Smithsonian magazine. She recalled being photographed by a news reporter while working in Ann Arbor as a metal presser during the war and genuinely thought she recognized herself in Miller’s illustration.

After Doyle passed away in 2010, many media outlets memorialized her as the “real Rosie.” Subsequent investigations, however, suggest the woman depicted in the poster may have actually been California-native Naomi Parker Fraley, who died in 2018. Since the “We Can Do It!” poster was never directly attributed to Rosie the Riveter, one could make the argument that neither woman was the original.

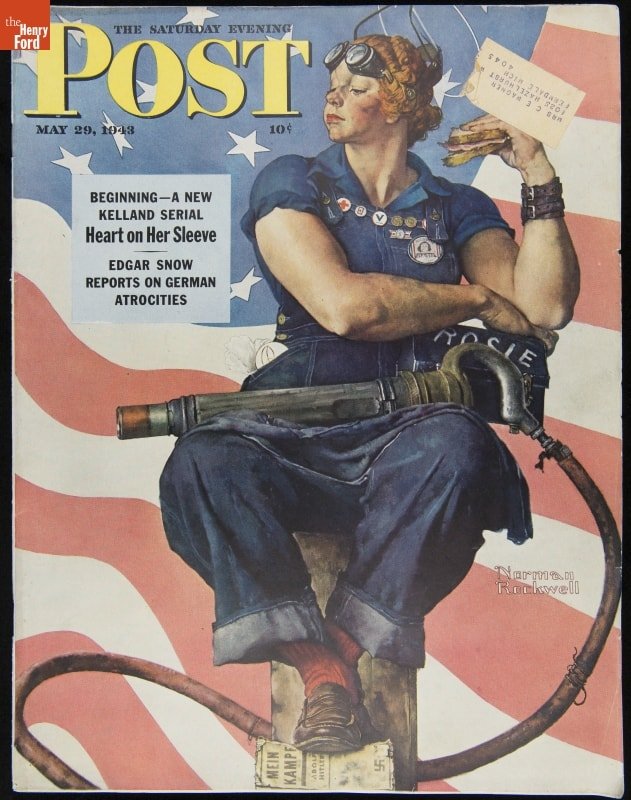

The first illustration to truly reference Rosie was a Norman Rockwell painting that appeared on the cover of the May 29, 1943, edition of the Saturday Evening Post, titled “Rosie the Riveter.” The image of Rosie is actually based upon Michelangelo’s painting of the Prophet Isaiah, which appears on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Her arms are quite muscular, perhaps representing the incredible strength of the women who stepped up to support their country in its time of need. At the same time, Rockwell’s Rosie is clearly feminine: she wears lipstick to work, polishes her fingernails, and carries a lacey handkerchief in her pocket. Also interesting are Rosie’s head and feet — she stands on a copy of Hitler’s “Mein Kampf,” and an angelic halo encircles her head.

The Treasury Department obtained permission to feature the painting in an ad campaign to promote the sale of U.S. war bonds; however, this image quickly faded from the public eye too, probably because the work was copyright protected and owned by the Rockwell family.

The Rosie the Riveter campaign certainly did exist, but the “official” images, published by the U.S. Office of War Information, were mostly photographs of women in the workplace and not the artwork the popular media has highlighted over the years.

Rosie’s place of employment — the Willow Run Bomber Plant, an hour west of Detroit — is as important to her story as the famous artwork that depicts her. This factory came to be one of the most impressive manufacturing accomplishments of the 20th century, and it was one of the earliest wartime recruitment centers for female laborers.

In the years leading up to the war, the Roosevelt administration was barraged by criticism that the United States military machine was ill-prepared for the storm that was brewing in Europe. While it was apparent that an effective military response would most certainly have to include modern air power, the pre-war fleet included fewer than 3,000 aircraft, many of them obsolete.

On May 26, 1940, President Franklin Roosevelt addressed the nation in one of his famous “fireside chats,” announcing the government intended “to harness the efficient machinery” of private industry to manufacture 50,000 planes per year, more than all of the aircraft built in the United States since the birth of flight at Kitty Hawk 37 years prior. Roosevelt implored industry to speed up production capabilities to meet these demands.

There was a consensus among the president and his advisors that long-range, high-altitude bombers would be the key to establishing superiority in the air. The B-24 Liberator, designed by San Diego-based Consolidated Aircraft, was at the top of the list. Indeed, at that point in history, the Liberator was the largest and most complex airplane in the world. Compared to its B-17 predecessor, the four-engine Liberator was faster with a top speed of 300 mph. The B-24 also offered a larger payload with its dual bomb bays, initially capable of carrying 4 tons of bombs (later expanding to 6 tons). The behemoth could also fly 3,000 miles on a single tank of fuel.

By 1940, a handful of Liberators had already been produced for England and placed into service. However, Consolidated lacked the capacity to mass produce the aircraft. Much to the chagrin of the aviation industry, the War Department selected Ford Motor Company as one of the primary manufacturers of the Liberator. Dutch Kindleberger, president of North American Aviation, publicly ridiculed the Roosevelt administration’s decision to select Ford when he said, “You can’t expect a blacksmith to make a watch overnight.”

Although it would not be an easy task, Ford’s production chief, Charles “Cast Iron Charlie” Sorenson proved the critics wrong. Sorenson, often credited as being the brainchild of the first moving assembly line in the automotive industry, was the driving force behind the production logistics at Willow Run. In the January 2019 issue of Assembly magazine, writer Tim Trainor penned a fascinating account of Sorenson’s first visit to the Consolidated plant in San Diego. After the initial tour, Sorenson was less than restrained in his criticism of the current-state B-24 manufacturing process. “They were producing a custom-made plane put together as a tailor would cut and fit a suit of clothes,” he said. “No two were alike.”

Sorenson reportedly stayed up all night in his hotel room, sketching the entire assembly process on the backsides of placemats, embracing the same tried-and-true principles he had employed to perfect automobile manufacturing. Over breakfast the next morning, Sorenson shared his drawings with Edsel Ford and his team, who enthusiastically approved them on the spot.

Over the next six months, Sorenson flew large teams of engineers and draftsmen back and forth between Detroit and San Diego to learn every square inch of the B-24. Unfortunately, they soon discovered that Consolidated’s prints were virtually useless due to omissions of critical information, careless errors, and the use of nonstandard engineering symbols.

According to Trainor, “‘Cast Iron Charlie’ had two Liberators flown to Dearborn where they were systematically dismantled, piece by piece. A thousand-member tool design group worked around the clock seven days a week for almost a year to create three-dimensional schematics of the plane’s 30,000 separate components, generating five million square feet of blueprints in the process. Their work guided custom designs of 1,600 machine tools and 11,000 fixtures, some 60 feet tall, that would stamp, mill, drill, broach and grind parts to thousandths-of-an-inch tolerances, each with repeatable precision.”

In the meantime, other forces at Ford were working feverishly to design and build a facility to house Sorenson’s B-24 assembly line. Albert Kahn, perhaps Detroit’s best-known architect, was hired to design the Willow Run Plant. Kahn famously proclaimed that the factory would be “the most enormous room in the history of man.” This was no exaggeration. The design called for a 3.5-million-square-foot footprint that was more than a half-mile long, a quarter-mile wide, and it literally became the largest factory in the world.

The site selected for the massive undertaking was an 1,875-acre plot of land owned by Ford in Ypsilanti, Michigan, about 40 miles southwest of Detroit. Construction began on April 18, 1941. Incredibly, the plant began manufacturing parts just six months later — even while some walls and sections of the roof remained unfinished. On Dec. 4, 1941, just three days before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the first section of the adjacent Willow Run airfield opened for operation.

Early on, some of the criticism leveled at Ford by the aviation industry seemed to be justified. The automaker faced many challenges when it tried to apply to mammoth airplanes the same mass production techniques used for cars. According to Assembly’s Tim Trainor, “Automobiles of the era had 15,000 parts and weighed around 3,000 pounds. Sixty-seven feet long, the B-24 had 450,000 parts and 360,000 rivets in 550 sizes, and it weighed 18 tons.”

Ford found it difficult to quickly adapt tooling to accommodate rapid and ongoing design changes for the aircraft. To make matters worse, workers were reluctant to travel outside the Detroit city limits to Willow Run. The wartime gas rationing made travel difficult, and Ypslanti was essentially farm country with little housing available for workers.

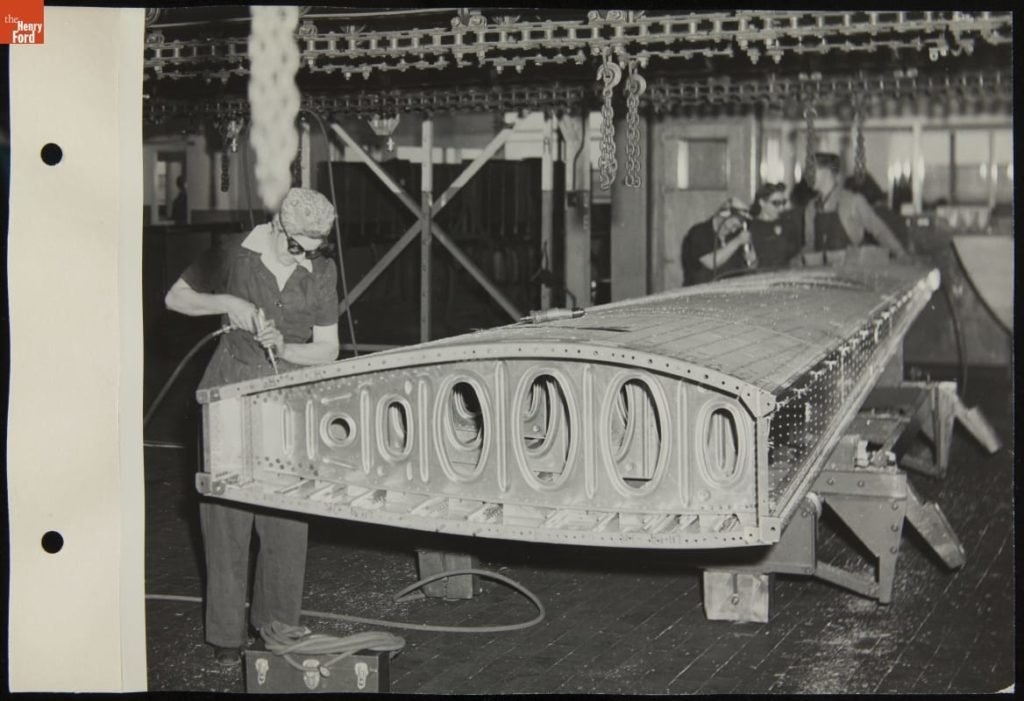

However, Ford quickly overcame these issues to prove the naysayers wrong. The plant would go on to achieve incredible rates of production. Nearly half of the military’s 18,000 B-24 Liberators were produced at the Willow Run plant. At the factory’s peak in 1944, one B-24 rolled off the assembly line every hour. By 1945, workers — many of them women — managed to complete 70 percent of total production in two 9-hour shifts.

Pilots and crew members slept in a nearby hangar on some 1,300 cots, waiting to test each new aircraft. The eastern Michigan skies would have been continuously darkened by B-24 planes being put through their paces — dives, climbs, stalls, and even simulated bombing runs.

A few weeks ago, I followed Rosie’s footsteps back to the Willow Run site. My visit started at the nearby Yankee Air Museum, which is spearheading the effort to restore what’s left of the plant. Here I met my tour guides — Claire Dahl, resident expert on all things Rosie (and dressed head-to-toe in her work uniform), and Kevin Perlongo, Bomber Plant Site Coordinator, who spent 30 years working in the plant after its post-war purchase by General Motors. Over the next two hours I rode in a small vehicle that most would call a gas-powered golf cart. For me, however, that four-wheeled contraption was nothing short of a time machine.

While the Willow Run airport is still operational (home to a few cargo airlines and some companies offering charter flights), only a small portion of the bomber plant still stands. Of the 3.5-million-square-foot facility, a 144,000-square-foot structure remains. Ironically, this section had been the very end of the assembly line, where painting, load balancing, final adjustments, and fueling were performed.

Standing outside, you can see the original, massive, and still-functional overhead doors on one side of the structure. Through these doors, 8,645 finished and fueled B-24 Liberators exited the plant. Also clearly visible high up on the outside walls was an odd-looking railing that surrounded the perimeter. On the original Kahn drawings, this structural feature was called a mounting rail, presumably for hanging lighting or similar electrical hardware. In reality, however, they were tracks for the blackout curtains that were to be deployed in the event of an enemy air raid.

Perlongo explained that there was a genuine concern that the Nazis could potentially stage attacks from nearby Canada if England were to fall. At the onset of the war, Canada still belonged to the British Commonwealth. When the Nazis initiated bombing campaigns over England, the British government quickly moved to develop contingency plans for defending against a full-on invasion. Gold reserves totaling $60 billion were covertly transferred to vaults in Canada. Furthermore, an elite team was established to smuggle England’s future Queen Elizabeth II and other members of the royal family to a secret “exile palace” near Victoria, British Columbia. The fate of England was uncertain and, therefore, so was that of Canada.

Inside the building, Perlongo took me to the fueling bay and pointed out the massive network of pipes, valves, and air cushions that once fed the fuel tanks. He was also eager to show off an interior room formerly known as “the vault,” a small 20×30-foot area that was used to secure the U.S. Army’s top-secret Norden bombsights. The sights were part optic and part analog computer. During missions, the bombardier would use the various knobs and switches to enter data into the instrument to compensate for variables such as wind, aircraft speed, and distance from target. The computer used this data to calculate and control the release point for the bombs. Pilots and crew took an oath to protect Norden sights with their lives.

When Rosie the Riveter was mentioned, Perlongo’s eyes lit up and he quickly ushered me to a table with stacks of old drawings and photographs. He shuffled through one of the stacks and smiled when he found the one he was looking for. It showed a boxy vehicle on wheels parked inside the plant with a large, open, walk-up window. Many Rosies were standing in an orderly line leading to the window.

At first glance, it looked like a giant food truck. But Perlongo drew my attention to a small detail: inside the vehicle, clearly visible through the open window, was a fully automatic “Tommy” gun mounted on the wall. The vehicle was an armored truck dispensing wages on payday. Ford management insisted upon paying the Willow Run workers in cash.

After walking through the rest of the bomber plant space, we drove over to another nearby structure known as “Hangar 1.” Perlongo said that the hangar had been used to complete miscellaneous post-production adjustments and provide housing for the hundreds of pilots and crew who put each new aircraft through its paces. Dahl showed me several of the Yankee Museum’s World War II-vintage planes being stored at Hangar 1, including the B-17 “Yankee Lady” and B-25 “Yankee Warrior” planes, which are still in service.

Dahl went on to explain that Hangar 1 will be decommissioned for aircraft storage by the end of 2019. The Yankee Air Museum has undertaken a large fundraising effort to build a new hangar inside the bomber plant. The long-term vision is to move the entire museum into the plant as well. At that time, it will become a national museum, operated by the U.S. Department of Interior and the National Parks service.

Driving back to our vehicles, I imagined it was the end of my day shift at Willow Run. As I left the parking lot, I felt the presence of Rosie sitting in the passenger seat beside me.

Rosie’s real name is Mary Helena King — born May 6, 1912, in Grand Rapids, Michigan. After graduating high school at Grand Rapids Catholic Central, she attended Western Teachers College, which would later become Western Michigan University.

During her college years, Mary met two men named George who competed for her affection. George No. 1, a tall athletic young man and first baseman for the Western baseball team, would win her hand in marriage. They settled in the River Rouge area of Detroit, where Mary gave birth to two children, Patricia and Richard.

According to the Encyclopedia of American Economic History, the “Rosie the Riveter” campaign increased the number of working American women from 12 million to 20 million by 1944, a 57 percent increase from 1940.

In 1938, a little over a month before from the couple’s four-year anniversary, George No. 1 filed for divorce, leaving Mary with their two young children. He wrote occasional letters to Patrica and Richard, but that was the extent of this contact with his children before enlisting in the U.S. Navy as a medic. He eventually shipped out to the Pacific, rose through the ranks, and took command of an amphibious Landing Ship Tank (LST) vessel. George No. 1 survived the war but never visited his children.

Devastated, a single mom with nowhere to go and the worry of war hanging over her head, Mary moved in with a close friend in Detroit. According to human resource records obtained from the Henry Ford archive, Mary started as a stock checker at the Willow Run bomber plant on July 31, 1942. Her starting wage was 90 cents per hour.

A few months later, she was promoted to tool crib clerk. During her time at Willow Run, Mary floated between several positions and performed varied duties. Although never actually handling a rivet gun, she was always close to the aircraft assembly line. She would suffer from chronic tinnitus the rest of her life and, ultimately, permanent damage to her inner ears. Doctors attributed Mary’s loss of hearing to the work she performed at Willow Run, but she steadfastly refused to seek financial compensation from Ford or the U.S. government.

Shortly before Mary was hired at Willow Run, George No. 2 enlisted in the Navy. Stationed in Europe, he would see action at Normandy on D-Day, providing covering machine gun fire as his amphibious boat shuttled troops to the beach.

When asked later to recount the experience, he laughed, shrugged his shoulders, and admitted that he had no idea what he was shooting at. “It was total chaos,” he said. “I just aimed and fired where they told me to.”

After sifting through the fact and fiction of Rosie lore, exploring the history of her place of employment at the Willow Run Bomber plant, and taking a trip across the state to follow in her footsteps, only one question remains: Who the heck is Rosie? As Paul Harvey would say, “and now … the rest of the story.”

Upon her marriage to George No. 1 in 1934, Mary King became Mary Cooper. Richard, her son, is my father. Rosie, in this instance, is my grandmother.

Grandma Mary left Willow Run at the end of the war in 1945. She, Patricia, and Richard went back to her hometown of Grand Rapids and moved in with her parents. Not too long after that, George No. 2 — George Fraleigh — returned home from the Navy and accepted a job at the Brown Company paper mill in Kalamazoo, Michigan. It wasn’t long before he discovered that Mary, his old college flame, was single again. The pair reunited, resumed a courtship, and eventually tied the knot on a summer day in 1951.

During their 41-year marriage, Mary and George were an inspiration to everyone in their family. They were devout Catholics, and their home was a safe haven when times were turbulent. Dinner always included fresh vegetables from George’s legendary backyard garden, and dessert was a piece of Mary’s pie made with the best, made-from-scratch crust you’ve ever tasted. George died in 1992, when he was 82 years old; Mary lived another 10 years, passing away at the age of 94.

Growing up, I learned tidbits of information about their service during the war. Only now do I truly appreciate how their contributions — and the contributions of so many like them — saved the world from utter catastrophe.

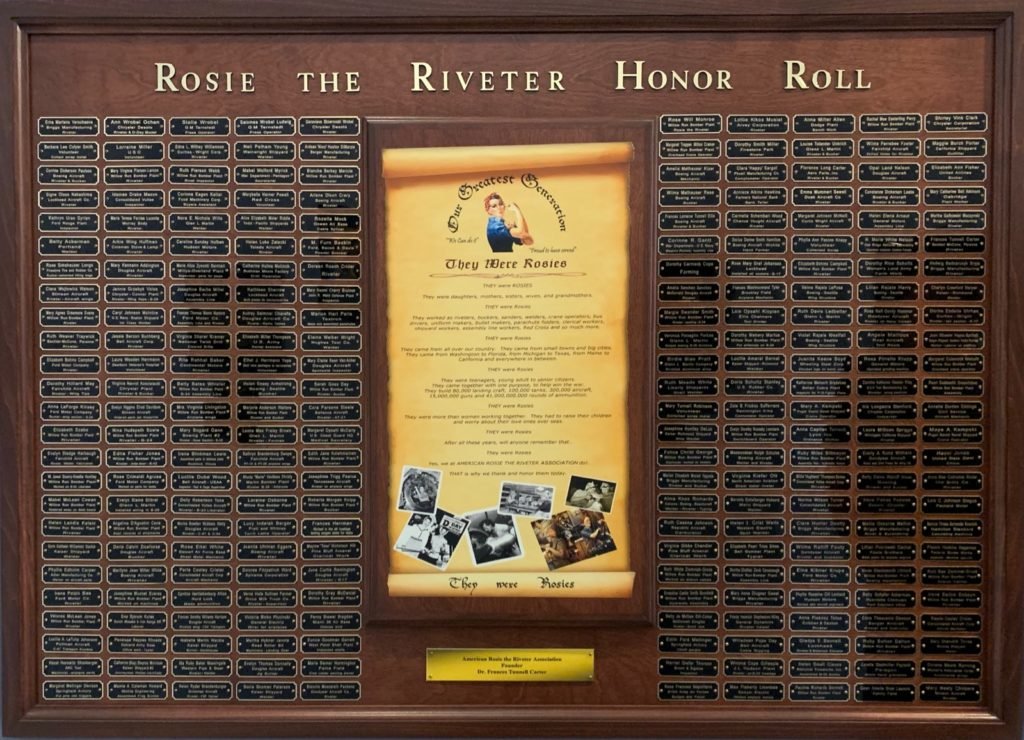

Of course, my grandmother was not the only Rosie — there were literally millions of these incredible women, every bit as special as Mary. According to the Encyclopedia of American Economic History, the “Rosie the Riveter” campaign increased the number of working American women from 12 million to 20 million by 1944, a 57 percent increase from 1940.

Mary King’s name will soon be added to the Rosie the Riveter Honor Roll plaque at the Yankee Air Museum in Ypsilanti. She may not have been one of the original models who posed for Westinghouse or Norman Rockwell, but she is a real Rosie all the same.

Tim Cooper is a contributing writer for Coffee or Die and has been a freelance writer for more than 20 years. He is also a certified firearms instructor and soon-to-be-famous recording artist with Fat Chance Records. When Tim is not traveling the world on assignment, which is actually more often than not, you will probably find him at a nearby shooting range or sitting behind a drum kit, staring at his bandmates in bewilderment.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.