The Japanese-American Who Was Merrill’s Marauders Eyes and Ears on the Battlefield

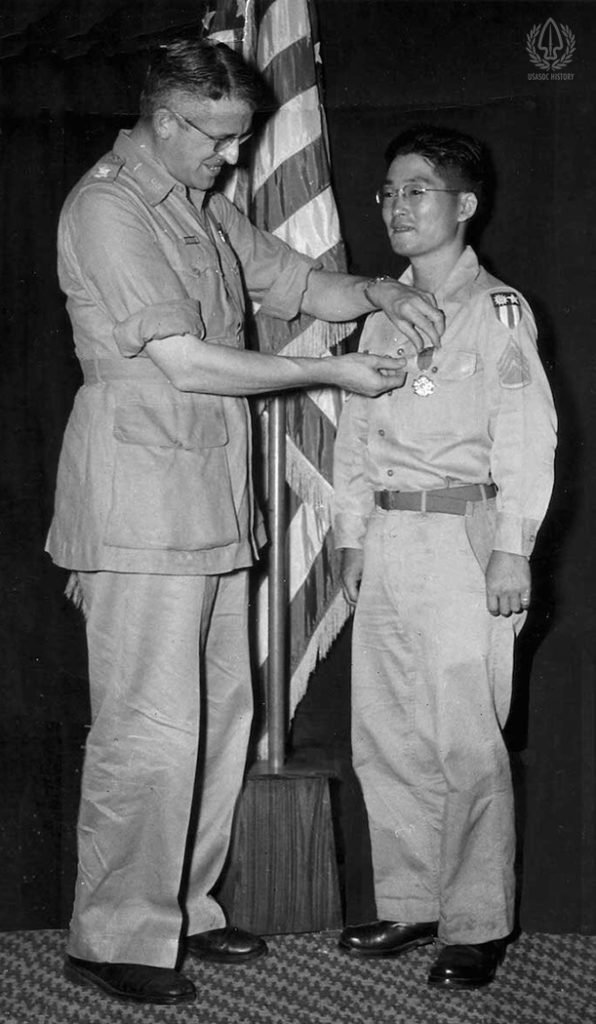

General Frank Merrill of the famed Merrill’s Marauders congratulating S/Sgt Roy Matsumoto for earning the Legion of Merit award, photo courtesy of Densho Digital Repository.

Survival was a long shot for the 600 remaining soldiers of 2nd Battalion, 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional). Codename Galahad, the famed Merrill’s Marauders were the first American troops to fight the Japanese in Asia, and are the predecessors of the modern day 75th Ranger Regiment. They braved daily onslaughts of artillery barrages and mortars that left man-sized craters. Small-arms fire forced them to bury their faces in mounds of dirt, never knowing if one of the bullets passing overhead would hit its mark. The Japanese crept closer and closer, surrounding their position.

It was the ninth day of being completely surrounded at Nhpum-Ga, Burma, a rocky hilltop village that spanned 400 yards long and 200 feet wide, and a ground attack was imminent. The area would later be known as Maggot HUP because of the rotting dead bodies that laid unburied and the decaying mules that emitted a gagging stench under the suffocating humidity.

The platoon leader, Lieutenant Colonel Edward McLogan, reflected on his experience in Patrick O’Donnell’s “Into the Rising Sun: In Their Own Words, World War II’s Pacific Veterans Reveal the Heart of Combat“: “The odor was so intense you had to breathe through your mouth instead of your nose.”

Resupply from the air, often intercepted outside the perimeter, deepened their desire for the precious fried chicken, bread, and ammunition that had fallen into the hands of the enemy. The airdrops hinted at their desperation to outlast the experienced jungle fighters from the Imperial Japanese Army’s 18th Division. It was the same division responsible for bringing the British to their knees in the fall of Malaya and Singapore.

Each night, Sergeant Roy Matsumoto would sneak out to the edge of the hill and gather intelligence on the loud and boastful enemy. One night around 10 o’clock, Matsumoto couldn’t quite make out what was being said only a few hundred feet down at the bottom of the hill. He handed his ammunition and carbine rifle to McLogan and told his Battalion Commander, Colonel McGee, that he was going to crawl out there.

After they exchanged passwords for security, Matsumoto grabbed two hand grenades and stuffed them in his pocket as insurance — capture meant certain suffering. He crawled on his hands and knees into “no man’s land” to better hear the mumbling voices in the night. Lying still, he quieted his breathing to process every word muttered from a group of soldiers mere meters away.

And then he listened.

Designated ‘Enemy Alien’

Born in Laguna, California, Matsumoto moved to Hiroshima, Japan, to live with his grandparents when he was 8-years-old. In Japan, he felt discriminated against for being an immigrant while attending school; he faced a similar experience when he returned to the U.S. in his teens to graduate from Long Beach Polytechnic High School in 1933.

The attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, created a fear within the U.S. government that Japanese-American sleeper cells would rise up to attack targets on the mainland or, at the very least, conduct espionage. What followed is considered one of the most nefarious infringements on American civil rights in the 20th century.

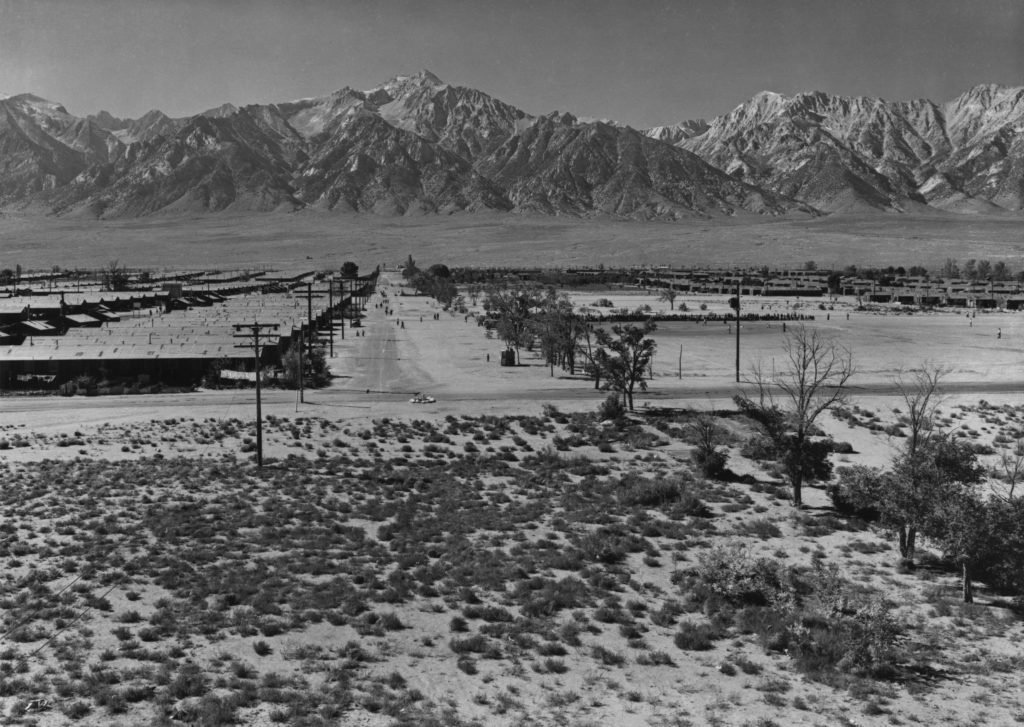

Matsumoto was imprisoned at Jerome Relocation Center in Arkansas, the last of the 10 internment camps erected in 1942. He and 8,497 of the 120,000 total Japanese citizens from the West Coast were forced into these camps by the U.S. military under Executive Order 9066, signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Matsumoto was imprisoned at Jerome Relocation Center in Arkansas, the last of the 10 internment camps erected in 1942.

He worked in the mess hall passing out bread and vegetables, and he described sleeping in horse stalls and on top of manure. “I witnessed that — American educated or Japanese educated, using the psychology, you know, no wonder some people get mad,” he recalled in a taping of his life’s oral history. “I wanted to get out any way except for escaping because the machine gun was facing not outside to protect us, but facing us so we don’t escape. Some camps and some people went near the fence and were shot and killed.”

Another notable Jerome internee was Joe M. Nishimoto, a Nisei who was assigned to a different theater of operations. He was later awarded the Medal of Honor for crawling through a minefield in France, destroying a machine gun emplacement with a grenade, assaulting another with his rifle, killing one and wounding another. Before his blitz was finished, he forced another machine-gun position to flee, doing so as a one-man army. He also received the Silver Star for heroism in Italy by spotting four boobytraps attached to anti-personnel mines, sneaking within 15 yards of the enemy, dropping a grenade onto their position, and capturing those who survived.

Those who were imprisoned were labeled as “enemy aliens,” despite their American citizenship. This angered many, including Matsumoto, and when a U.S. Army recruiter came by asking for volunteers, he jumped at the chance to serve the country that turned its back on him. The irony was unmistakable — imprisoning Japanese-Americans for who they were, then ultimately recruiting them for what they had: an understanding of the language, culture, geography, and customs of the enemy.

Military Intelligence Service Language School

Despite the imprisonment of thousands of Japanese because the government believed that they couldn’t be trusted, Nisei (second generation Japanese-Americans) and Kibei (American born but Japanese educated) linguists became some of the most valuable assets in the Pacific. Japanese war planners, cocksure in their difficult native language, hadn’t considered Japanese-American assets, and so they grew careless with their codes, secrets, and messages. The Nisei proved themselves by leveraging a groundbreaking advantage in psychological warfare and counterintelligence.

Following graduation from the Military Intelligence Service Language School (MISLS, or more simply MIS) — the predecessor to the Defense Language Institute — Japanese soldiers were assigned to their units to act as interrogators and translators of captured enemy documents, aiding in the creation of both black and white propaganda. In addition, they worked alongside other allied nations — Australia, Canada, Great Britain, India, China, and New Zealand — to effectively provide their capability as the eyes and ears of each battalion across the battlefield.

President Harry Truman referred to the MIS as “the human secret weapon for the U.S. Armed Forces.” Some Nisei helped translate Japan’s “Z Plan,” their defensive strategy to launch an all-out attack against the American Pacific fleet from their last strategic position in the Mariana Islands. The captured plans were the most highly coveted during World War II. By the war’s end, 20.5 million papers were translated by the Nisei.

Matsumoto called out in native Japanese, “Totsugeki-Ni!” or “Charge! Charge!” while motioning for them to race to their feet and attack his own position.

Matsumoto, alongside only 13 Nisei, volunteered for Merrill’s Marauders and were not deterred by the expected 85 percent attrition rate. Their mission was to secure a supply route to China by utilizing the Burma Road. Without ground support, a quick reaction force, artillery, vehicles, or much more than what they could pack in on mules, Merrill’s Marauders trekked through more than 1,000 miles of dense jungle. For Matsumoto, all 125 pounds of him, he was closing in on his chance to prove his worth while carrying half his body weight in gear.

Intelligence & Reconnaissance

“I happened to be assigned to the blue combat team I&R,” Matsumoto told the Densho Visual History Collection. “I&R stand [sic] for Intelligence & Reconnaissance, in other words a scout unit.” For every 500 men, only two were linguists. In the beginning, it was one Nisei and one Kibei working together. The combination worked as the Nisei were stronger in English and the Kibei spoke better Japanese.

When they first came into contact with the enemy, they learned to always check the dead for booby traps. “Each one carried a Japanese flag that signed by the neighbors and relatives for good luck, good wishes,” Matsumoto said. “And they carried that flag. Then people tried to get souvenir, then hurt because somebody was booby trapped or they waiting with a machine gun go out there.”

One of their main practices was searching for live wires they could tap into using a clip. While on patrol, Matsumoto spotted a line, climbed a tree while exposed to sniper elements, and sat on the branch. Using a telephone, he heard two Japanese soldiers talking back and forth. The information he collected led to actionable intelligence his rifle platoons could take advantage of.

Heroism on Maggot Hill

Matsumoto hurried back to relay the unsettling intelligence he gathered to Lieutenant Edward McLogan. “You’re not going to like what I’m about to tell ya,” Matsumoto said. “They’re going to concentrate and attack this portion of the hill.” At sunrise on the morning of April 5, 1944, Easter Sunday, the Japanese would launch a surprise raid with a force estimated at 2,500 infantryman.

In the meantime, their unit moved back from their abandoned foxholes, laid booby traps inside them, took the high ground, and waited with their carbines, Thompson submachine guns, and BARs aimed downward. Japanese raiders broke over the hill, charging with their bayonets. “Banzai!” they yelled. Once they hit the booby traps, an officer carrying a sword pointed to advance farther up the hill. Fifteen yards away, the first Japanese soldier was torn apart as more than 50 Americans fired their weapons. The first wave was dispatched with extraordinary accuracy.

“This tactic works for any interrogator — kindness kills.”

Matsumoto moved from cover and exposed himself to the assault. Instead of firing immediately, he faced the enemy, many of whom had taken cover against the rocky dirt. Matsumoto called out in native Japanese, “Totsugeki-Ni!” or “Charge! Charge!” while motioning for them to race to their feet and attack his own position. Confused, the second wave of Japanese fighters ran up the hill to follow the man they thought was one of their officers, only to see him firing his carbine and dropping several of them. All their attention was focused on Matsumoto, which allowed his teammates to open fire with the same ferocity that the first wave received.

The numerically superior Japanese army returned fire, and bullets zipped and snapped over the Americans’ helmets. Nearby trees and concealment disintegrated as if they were never there to begin with. As the chaos ceased, there were two officers amongst the 54 dead Japanese; several hundred more were wounded.

Sergeant Warren T. Ventura later wrote, “When I asked our commanding officer, Lt. Col. George McGee why this man was not recommended for the Medal of Honor, he told me that ‘he was only an enlisted man doing his duty. Enlisted men do not get medals for this.’”

Continued Service and Recognition

Unfortunately, Merrill’s Marauders received the same fate as many early special operations units and was disbanded in August 1944. Matsumoto continued his service as an intelligence specialist and was reassigned to Detachment (Det) 202 of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). The unit worked outside of the previous tandem relationship between OSS and the SACO, which gave them the lead in commanding their Chinese counterparts.

Matsumoto operated in the Indo-China-Burma theater for more than six months in various roles, including face-to-face interactions with prisoners of war (POWs). The Japanese expected the worst from their captors, and Matsumoto exploited that mindset.

“This tactic works for any interrogator — kindness kills,” he said. Matsumoto offered a fresh meal and cigarettes to a terrified Japanese prisoner brought in by a Chinese commando. He earned his trust by speaking in his native tongue. Most Japanese soldiers gave only their name, rank, and serial number, and expected certain torture and even death. Matsumoto, working his tactic, gleaned significantly more information.

He also worked post-war assignments, which included escorting 24 war criminals to be imprisoned in Sugano, Japan. Matsumoto traded in his uniform for civilian attire and participated in undercover assignments, which he vowed to never speak about in detail. He retired in 1963 with 20 years of accumulated service.

In 1993, he was inducted into the Ranger Hall of Fame; the Army Special Forces made him an honorary member, citing his stint with the OSS; and, in 1997, the Military Intelligence Corps Hall of Fame welcomed him into their exclusive ranks. In 2011, nearly 67 years after his unit was disbanded, Matsumoto — alongside other surviving Nisei — was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in a ceremony held in Washington, D.C.

Matsumoto died on April 21, 2014, a week before his 101st birthday.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.