Russian President Vladimir Putin Is Weaponizing His Gas. Will that Backfire?

Russian President Vladimir Putin enjoys the opening of Lukoil’s gasoline station on Sept. 26, 2003, in the Chelsea neighborhood of New York City. Lukoil, a Russian oil company, acquired Getty Petroleum Marketing Inc. and its 1, 300 stations in November 2000. Photo by Stephen Chernin/Getty Images.

This story by Michael E. Webber appeared first in The Conversation on April 29, 2022. The Conversation is a community of more than 135,400 academics and researchers from 4,192 institutions.

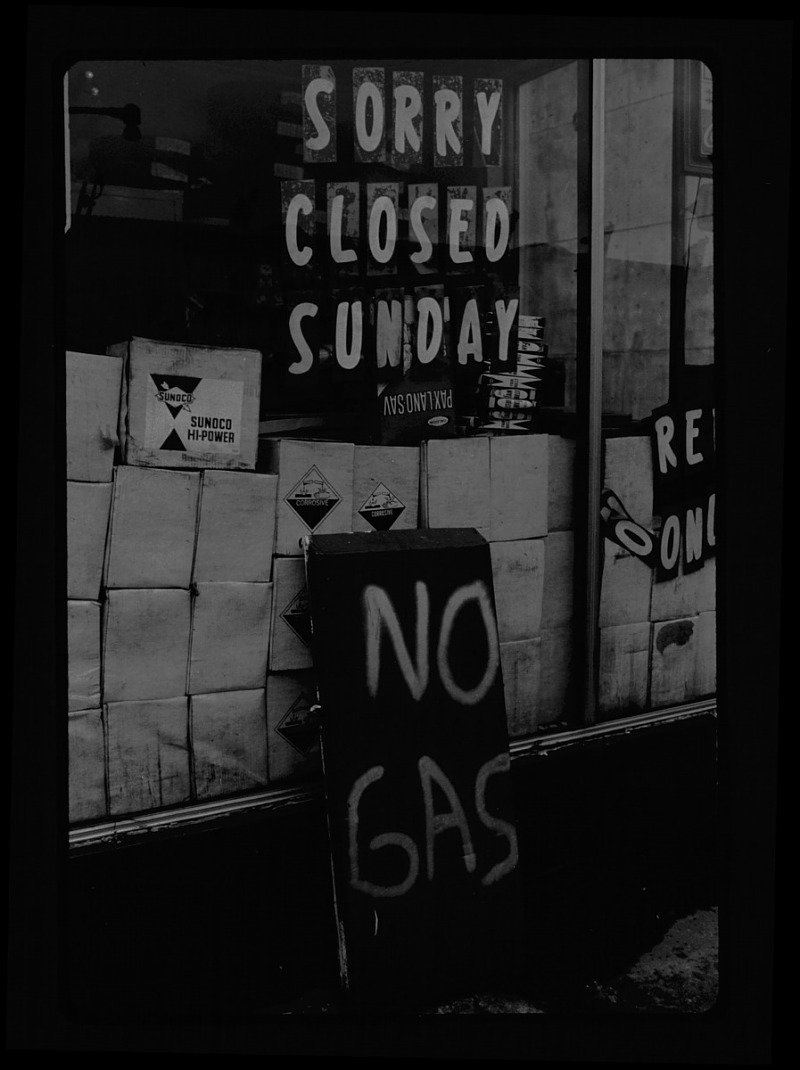

In December 2006, The Economist magazine published a cover drawing of Russian president Vladimir Putin, dressed like a 1930s gangster in a dark suit and fedora hat, under the headline “Don’t Mess with Russia.” Putin held a gasoline nozzle, gripping it like a machine gun. The target presumably was Europe, which relied heavily on Russia for oil and natural gas.

The cover story’s subheading asserted, “Russia’s habitual abuse of its energy muscle is bad for its citizens, its neighbourhood and the world.” Today that assertion still rings true with Russia’s cutoff of natural gas deliveries to Poland and Bulgaria.

As an energy scholar who has lived and worked in Europe, I know that gas is a precious commodity that is critical for industries, power generation and heating buildings – especially in northern Europe, where winters can be harsh and long. This explains why European nations import gas from many sources, but have grown to depend on Russian supplies to keep their homes warm and their economies humming.

From oil embargoes to gas cutoffs

The energy weapon can take many forms.

In 1967 and 1973, Arab nations cut off oil exports to the U.S. and other Western nations that supported Israel in conflicts against its Middle East neighbors. Withholding supply was a way to inflict economic pain on opponents and win policy concessions.

Today, an oil embargo might not work as well. Oil is a fungible commodity in a global market: If one source cuts off shipments, importing countries can just buy more oil from other suppliers, although they may pay higher prices on spot markets than they would have under long-term contracts.

That’s possible because more than 60% of the world’s daily oil consumption is delivered by ship. At any given moment, a flotilla of seaborne vessels is carrying crude oil from one point to another around the globe. If there are disruptions, the ships can change direction and get to their destinations within a matter of weeks.

As a result, it’s hard for one oil-producing country to prevent a consuming country from buying oil on the global market.

By contrast, natural gas is moved primarily by pipeline. Only 13% of the world’s gas supply is delivered by tankers carrying liquefied natural gas. This makes gas more of a regional or continental commodity, with sellers and buyers who are physically connected to each other.

It is much harder for buyers to find alternative natural gas supplies than alternative oil sources because laying new pipelines or building new liquefied natural gas import and export terminals can cost billions of dollars and take many years. Consequently, gas disruptions are felt quickly and can last a long time.

The real cost of buying Russian gas

European nations’ dependence on Russian energy, particularly natural gas, complicates their foreign policies. As many observers have pointed out since Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, European consumers’ heavy reliance on Russian oil and gas over the decades has funded and emboldened Putin’s regime and made European governments hesitant in the face of bad behavior. It was no accident that Russia invaded in February, when it’s coldest and European demand for gas for heating buildings is highest.

Because the European gas grid spans many countries, Russia’s shutoff of gas to Poland and Bulgaria doesn’t just affect those two countries. Prices will rise as gas pressures in the pipelines that run through those countries to other nations drop. The shortage will eventually ripple through to other countries further downstream, such as France and Germany.

If Europeans can reduce their gas consumption quickly as the heating season winds down and gas power plants are replaced with other sources, they can slow the onset of pain. Fuller use of liquefied natural gas imports from coastal terminals could also help.

In the longer run, the European Union is working to increase energy efficiency in existing buildings, which are already efficient compared to U.S. buildings. It also aims to fill gas storage caverns to 90% capacity during the off-peak seasons when gas demand is lower, and ramp up local production of biomethane – which can substitute for fossil gas – derived from agricultural waste or other organic, renewable sources.

Building more import terminals to bring in liquefied natural gas from the U.S., Canada or other friendly nations is also an option. However, creating new fossil fuel infrastructure would conflict with efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to slow climate change.

Ramping up wind, solar, geothermal and nuclear power plants as quickly as possible to displace the continent’s natural gas power plants is a key priority for the EU. So is replacing natural gas heating systems with electric heat pumps, which can also provide air conditioning during the continent’s increasingly frequent and intense summer heat waves. These solutions align with the EU’s climate objectives, which suggests that Russia’s gas cutoffs might ultimately accelerate European nations’ efforts to shift to renewable energy and more efficient use of electricity.

All of these options are effective but take time. Unfortunately, Europe doesn’t have many options before next winter. Prospects are worse for energy customers in poorer regions, such as Bangladesh and sub-Saharan Africa, which will simply go without in the face of higher energy prices.

Will Russia’s cutoff backfire?

While gas supply disruptions will undoubtedly inflict pain on European consumers, they also are hard on Russia, which badly needs the money. Currently, Putin is ordering “unfriendly” countries to pay for Russian energy in rubles to boost Russia’s currency, which has lost value under the weight of economic sanctions. Poland and Bulgaria had refused to pay in rubles.

Cutting off gas supplies in February would have been expensive for Russia and surely would have inspired even more backlash in Europe. By wielding natural gas as a weapon when the weather is mild, Russia can flex its petro-muscles without being too aggressive or losing too much money. The key question now is whether Europe needs Russian gas more than Russia needs revenue from European sales.

The Conversation is a nonprofit, independent news organization dedicated to unlocking the knowledge of experts for the public good.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.