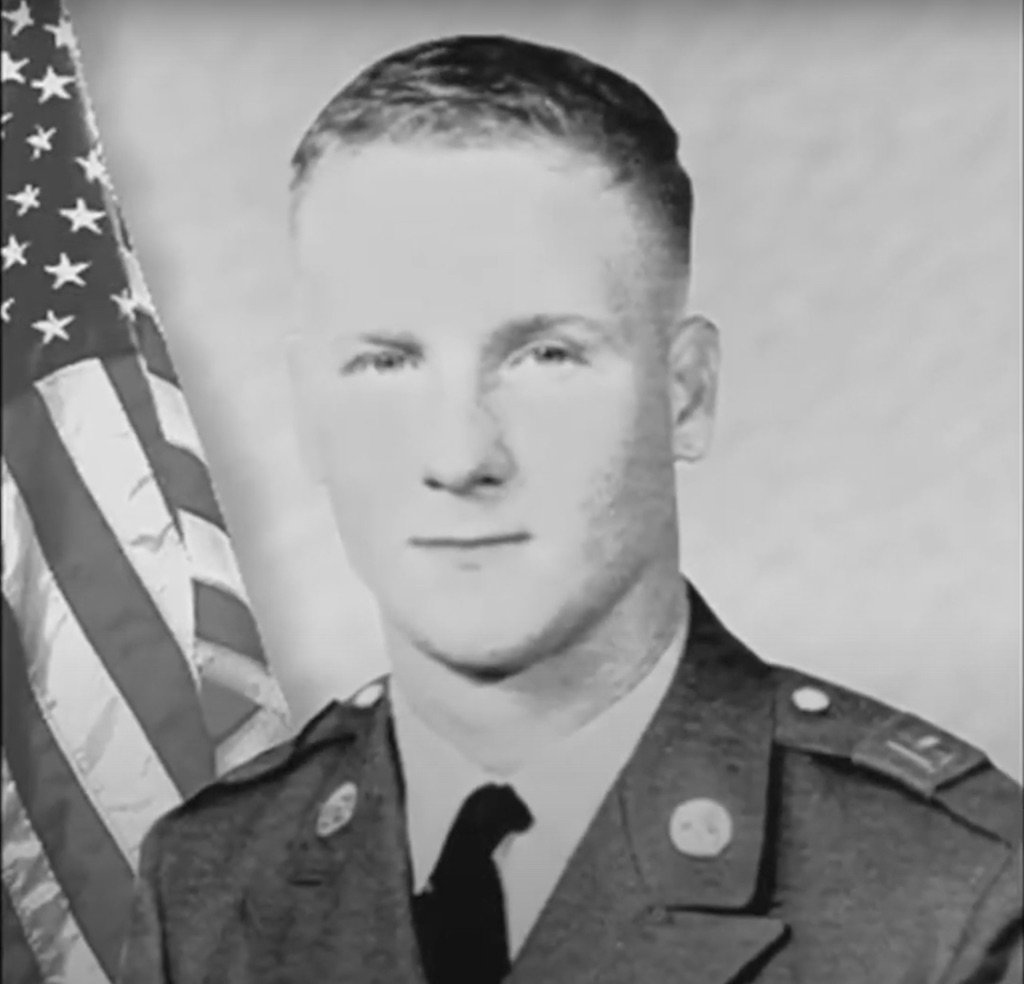

A Soldier & His Harmonica: Vietnam War Medal of Honor Recipient Sammy Davis

Sammy Davis (third from left) receiving the Medal of Honor from President Lyndon B. Johnson on November 19, 1968 along with four fellow recipients: Gary Wetzel, Dwight H. Johnson, James Allen Taylor, and Angelo Liteky. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Pfc. Sammy Davis didn’t write letters home because he didn’t want his mother to worry. His captain once waded through knee-deep mud and water to reach his position on the perimeter, then informed him his mother hadn’t heard from him in 63 days. Davis refused to lie to his mother and didn’t want to tell the truth about the violence of the Vietnam War, so he wrote postcards about rhinoceros beetles and their jousting matches. He wrote about the bananas in the jungles and the French pineapple plantations. He even drew a 10,000-legged worm three postcards long.

A few weeks passed and a package arrived in the mail. Inside was a note and a box. “Son, I hope this helps you be not quite so bored,” the note from his mother read. Inside the box was a harmonica. Staff Sgt. Johnston Dunlop, a volunteer with the US Army’s 9th Infantry Division’s Long Range Reconnaissance Patrol (LRRP), asked the young artilleryman to learn the song “Shenandoah.” Despite not knowing how to play the instrument, Davis practiced all day and night.

“We were artillery,” Davis later said at the 2011 Broadway Salute to Troops event. “It was okay that I played the harmonica all night. If the enemy didn’t know where we were, we weren’t doing our job.”

The LRRPs were an intelligence gathering force in Vietnam. “They were the ones that would determine where we as artillery would be moved in the following days so we could best support our infantry,” Davis recalled. “They would pick us up by helicopter and take us 100 miles away and set us down. Usually, just before dark, Sgt. Dunlop and his crew of three to five men would come in through the single-strand of barbed wire that we put around us. He’d find wherever I was at and he’d say, ‘Sam, play Shenandoah for me.’”

Dunlop attended school in Virginia before joining the military, and he’d drive to the Shenandoah River Valley whenever he felt stressed out. He’d sit and hang his feet over a rock and look down into the river to watch the trout swim by. When Davis played his harmonica, it helped Dunlop find peace in his heart, the same peace he felt when he sat by the Shenandoah River.

On Nov. 18, 1967, Davis and his unit from Battery C, 2nd Battalion, 4th Artillery Regiment, 9th Infantry Division, were airlifted to a small island in the Mekong Delta near Cai Lay, Vietnam. They landed at 8 a.m. and set up 11 105 mm howitzers and fired them all day long. After the Viet Cong broke contact with the infantry, a friendly helicopter landed, and a major hopped off. “Your probability of getting hit tonight is 100%,” Davis said he told them. “So prepare yourselves.”

Davis looked at his watch, which read 2 a.m. They could hear mortar shells sliding down the tubes, a frightening sound since they didn’t have any friendly mortar teams near their position. A barrage of enemy fire rained down on their positions and didn’t relent until 30 minutes later. Then, after an eerie silence, they heard the whistles. They could hear orders being shouted in English. “And basically what they were saying was, ‘Go kill the GI,’” Davis said.

A reinforced battalion of 1,500 Viet Cong assaulted his unit of only 42 artillerymen.

Davis readied his howitzer as he watched the enemy come closer, several of them bunched together in mass assault waves. When Davis fired the artillery weapon, an enemy rocket team targeted his muzzle blast. The rocket exploded at his position and knocked him unconscious. The Viet Cong overran his position and turned his howitzer to use it against his teammates. Another American howitzer emplacement behind his position fired a beehive round to destroy his howitzer to prevent the weapon from being used against them.

“A beehive round effectively turns a 105 howitzer into a shotgun,” Davis recalled in an interview for the book Medal of Honor: Portraits of Valor Beyond the Call of Duty. “It fires 18,000 little beehive darts. From midthigh up to and including my fourth lumbar vertebrae I had about 30 beehive holes that just passed through me.”

The impact jolted him awake and he rolled over onto his back. The bullets flying overhead reminded him of Christmas until he came out of his daze and realized the lights were tracer rounds. He grabbed his M16 rifle and expended 12 magazines of ammunition at between 150 and 200 enemy soldiers nearby. He fired his rifle until he ran out of ammo.

“I didn’t think I was probably going to see daylight, but I wasn’t going to quit,” Davis said. “If I don’t do my job, those guys behind me ain’t got a chance.” Davis hid himself in the water, lying perfectly still while the Viet Cong ran around him, then searched for the components to load the artillery piece when they looked away.

He loaded the howitzer and pulled on a lanyard to fire. Nothing happened. He had overcharged the canister with loose powder. Boom! The howitzer exploded seconds later with a flash that looked like a flamethrower. Davis loaded and fired the howitzer until he heard cries for help.

“Don’t shoot, I’m a GI,” Davis heard from across the river. He had little strength, but found a nearby air mattress they typically used to sleep on. He belly-crawled on the ground to reach the river and stashed the air mattress in the bushes. The GI was in a foxhole, huddled around two other Americans. Davis knew he was much too weak to make three crossings.

Davis made two painful trips across the river to rescue his wounded teammates and load them onto helicopters to be medically evacuated. After the fighting was over, 12 of the original 42 Americans were left standing, including Davis.

For his actions, Sammy Davis was awarded the Medal of Honor. The blockbuster movie Forrest Gump features footage of Davis’ Medal of Honor ceremony, except actor Tom Hanks’ head was edited in place of his. “It’s lightly, and I do mean lightly, based on me,” Davis said.

At the Vietnam Veterans Memorial dedication in 1982, Davis was invited as a guest speaker. He found the names of his teammates killed on Nov. 18, 1967, as well as the name of his friend, Staff Sgt. Dunlop. Standing in front of the wall, Davis touched Dunlop’s name, holding his harmonica in his other hand, and told him, “John, I’m going to play ‘Shenandoah’ for you brother, so you can get some rest.”

Since then, he has given speeches all around the country at schools and around the world on USO tours — bringing his harmonica along whenever he puts on his uniform.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.