Reliving History Through Firefighting Artifacts at San Diego Firehouse Museum

An inside look at the San Diego Firehouse Museum, located at 1572 Columbia St. in the Little Italy section of San Diego. Photo courtesy of the San Diego Firehouse Museum.

In 1915, Old Fire Station Number Six proudly served the community of Little Italy in downtown San Diego. Today, the location is home to the San Diego Firehouse Museum, which features firefighting memorabilia and artifacts dating back to the 1800s. Inside, the museum features relic equipment, both big and small, from fire rigs to sprinkler systems and peculiar gear used to suppress fires.

The most exciting artifacts, though, are the ones that are now considered woefully obsolete. To appreciate how far fire departments in the US have come, here is a look back at some of the most interesting artifacts found within this retired fire station.

Hydraulic-Lift Ladder Truck

This photograph shows a hydraulic lift ladder truck in 1896. Reputed to be the first one built on the West Coast, this fire truck required a driver to steer the horse-drawn rig and its crew of seven firefighters. Although there isn’t much information about its use, this type of vehicle is an archaic version of contemporary aerial firefighting rigs.

Old La Jolla

“Old La Jolla” certainly delivers the appearance one expects from a 19th-century fire service vehicle. A lantern for lighting in nighttime use, bells, hooks, and ladders are all attached to this hand-drawn fire engine on wagon wheels. It belonged to Hart Hook and Ladder No. 2 of a Logan Heights volunteer company in 1886.

“This hand-drawn rig was later rebuilt as a chemical engine, and from 1905 until 1913 it was La Jolla’s only fire protection,” the museum’s description of the artifact reads. “It is equipped with double trees, and if firemen encountered a delivery wagon on the way to a fire, they could commandeer the horse. This is the last San Diego volunteer rig existing.”

Fire Grenades

Not to be confused with Molotov cocktails, fire grenades are fire suppressant devices that predate fire extinguishers. Fire grenades were prevalent from the 1870s until the early 20th century — some were shaped like American World War II hand grenades, while others looked like light bulbs. Most often made of glass, fire grenades contained liquid carbon tetrachloride or saltwater, depending on the model.

The instructions for the Shur-Stop fire grenade, or “automatic fireman on the wall,” suggested throwing it at the base of the flames. There were also wall-mounted fire grenades that had no flash point and were not flammable. However, when heated to decomposition, the device emitted toxic phosgene and hydrogen chloride fumes — the same types of gases used during World War I chemical warfare. These models were discontinued.

Atlas Lifesaving Machine

“The Lifesaving Machine was used as a tool by Firefighters to allow people to escape from multistory buildings on fire,” the artifact’s description reads. “A person trapped up to five stories high could jump into the machine.”

The Atlas Lifesaving Machine was essentially a very large net with a red bullseye in the middle marking where the person should aim. This “Life Net,” as it was known in San Diego, required six firefighters to operate. The firefighters held it at shoulder height, while the fire captain called out commands to steer the crew in the proper direction.

“While training, Firefighters jumped from two to three stories high into the ‘Life Net’ landing on their backs,” the museum’s description continues. “‘Life Nets’ were taken out of service around 1980 because of injuries Firefighters received to their back, neck and arms and the reduction of Truck Company staffing from six person to four person.”

Fire ‘Sliding’ Pole

The first “sliding pole” to be used in a firehouse came to be thanks to the ingenious thinking of firefighter David Kenyon. It was 1878, and the firefighter from Chicago’s Fire Engine Company 21, an all-Black fire company, figured the sliding pole would improve their response times.

The company’s firehouse was a three-story building; fire lookout George Reed manned the top floor. When the other firefighters reached the main floor, they asked how he got there so fast. Reed replied, “I slid the pole.”

“The first Sliding Pole was a diagonal wooden pole, which was used to hoist hay to the 3rd floor where it was stored for horses,” author Dekalb Walcott Jr. writes in his book Black Heroes of Fire: The History of the First African-American Fire Company in Chicago. “When an alarm was received, everyone took the stairs except Firefighter Reed who slid the pole.”

Although Kenyon didn’t patent his idea, sliding poles became a staple for firehouses. The sliding pole in the San Diego Firehouse Museum represents a more modern design than the wooden sliding poles of the 19th century. Across the country, brass poles were removed in 1942 in support of the war effort and replaced with galvanized metal.

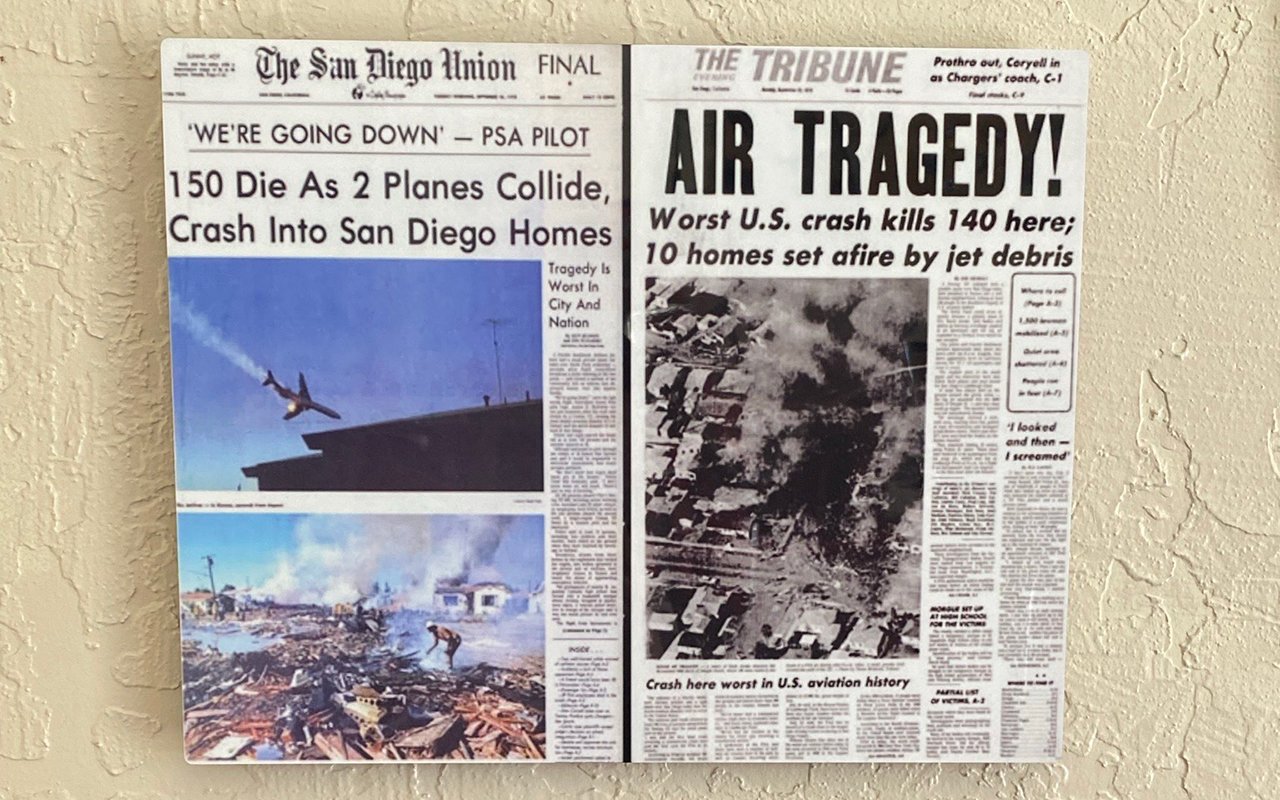

Aviation Disaster of 1978

Airplane disasters are one of the many dynamic emergencies to which firefighters respond.

At 9:02 a.m. on Sept. 25, 1978, a Pacific Southwest Airlines jetliner collided with a small private plane over North Park, a neighborhood in San Diego. Frank Herberar witnessed the collision from the ground. Along with hundreds of other people, he watched the Boeing 727 jetliner nosedive into the middle of a quiet residential area.

“There was a lot of stuff coming down,” Herberar later told The San Diego Tribune. “I saw this big piece up in the air and it came down slowly, kind of wobbly, and it landed about 15 feet from my car at the curb and about 20 feet from me. Another big piece of the plane landed about one and a half blocks away.”

Airplane parts, corpses, and flames destroyed or damaged 22 homes. All 135 passengers aboard the jetliner, the two people aboard the small plane, and seven people on the ground were killed. At the time, it was considered the worst aviation disaster in US history. Firefighter John Rankin along with his partner Steve Smith were some of the first responders on the scene that day.

Rankin and Smith split up to conduct house-to-house searches. “My feet didn’t feel right on what was supporting me,” Rankin later recalled, describing his attempt to drag a fire hose along the street. He realized he was “stepping on maybe 30 bodies […] just a mound of body parts.”

The horror of that unprecedented disaster is now remembered through the selfless actions of the firefighters and first responders who were on the scene that day.

The San Diego Firehouse Museum is open Thursdays and Fridays from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. and Saturdays and Sundays from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Admission costs only $3 for adults and $2 for seniors and children.

Read Next: How the New York Rangers Honored the FDNY’s ‘Master of Disaster’ After 9/11

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.