Sarin Nerve Gas Caused Gulf War Illness, New Genetic Study Claims

A sergeant with the 82nd Airborne Division wears a kerchief and sunglasses to help protect him from the dust and bright sun of the Saudi desert during Operation Desert Shield on Jan. 23, 1991. US Army photo courtesy of the US National Archives.

More than 30 years after Gulf War veterans began suffering from mysterious medical conditions, researchers said they have proven that exposure to sarin nerve gas caused the illness.

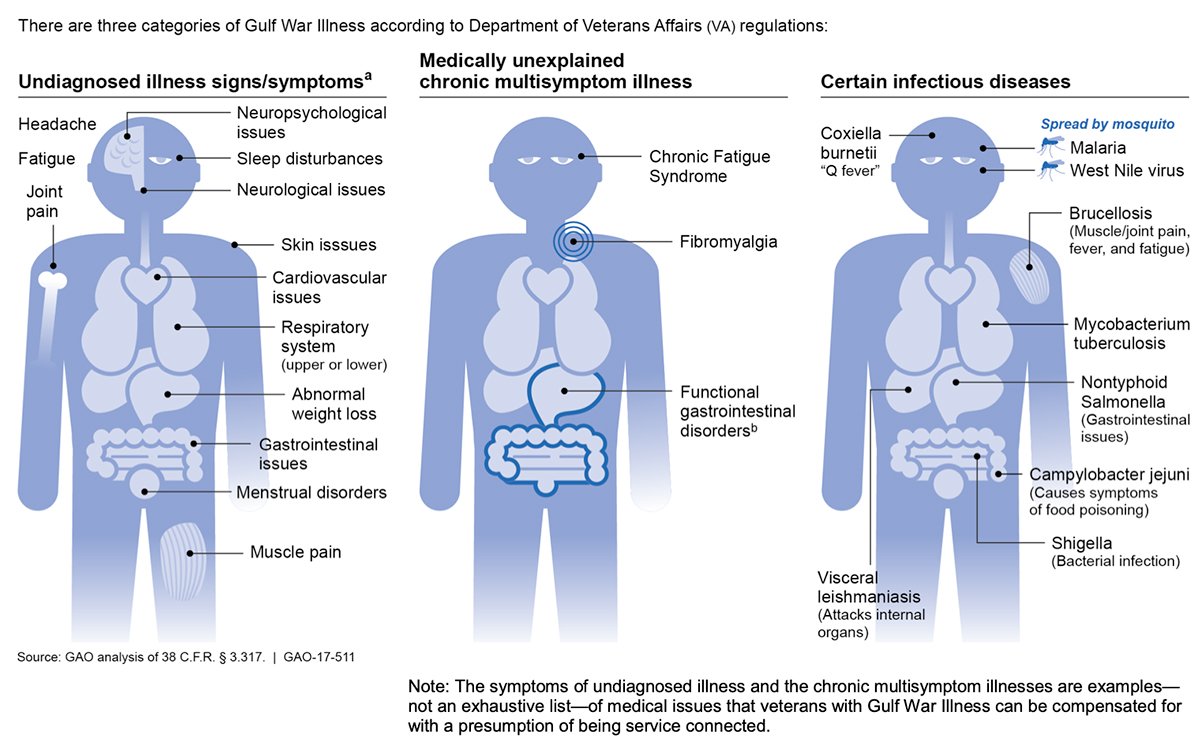

Around one-third of the 700,000 troops who deployed to the Gulf War theater of operations from 1990-1991 are believed to have been affected by Gulf War illness, according to the Defense Department. After returning home, veterans complained of a vast array of chronic symptoms, such as fatigue, joint and muscle aches, rashes, headaches, mood disorders, and respiratory problems. Doctors and federal agencies struggled to pinpoint an exact cause and for years blamed the symptoms on stress or other psychological disorders.

But a study published May 11 in the journal Environmental Health Perspectives used genetic research to point to one chemical agent in particular: sarin gas.

“Quite simply, our findings prove that Gulf War illness was caused by sarin, which was released when we bombed Iraqi chemical weapons storage and production facilities,” Dr. Robert Haley, a medical epidemiologist at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, said in a press release about the study.

Haley has studied Gulf War illness for 28 years and said that, while evidence always pointed toward nerve agent exposure as the cause, it was difficult to “build an irrefutable case.”

Sarin is a toxic nerve agent that was first developed as a pesticide in 1938 by scientists in Nazi Germany. But it was not used as a weapon until 1988, when Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein launched chemical attacks against thousands of Kurdish civilians.

Sarin attacks the neurotransmitters in charge of stimulating muscles, which, in the worst case scenario, can cause a person to stop breathing. It was banned in 1997, but there are allegations that Syrian president Bashar al-Assad used sarin against coalition forces and civilians on multiple occasions around 2013.

The Department of Veterans Affairs has acknowledged that upwards of 100,000 veterans may have been exposed to low levels of sarin and cyclosarin after coalition troops destroyed a munitions storage depot in Khamisiyah, Iraq, housing chemical weapons. A previous study by Haley and other researchers claimed winds may have blown the plume of sarin gas more than 300 miles to Saudi Arabia, however, affecting even more soldiers and often triggering nerve gas alarms.

The Findings

Haley and his team now believe the key to whether someone got sick following sarin exposure was a gene known as PON1, which helps the body break down pesticides.

According to Haley, there are two versions of the PON1 gene: the Q variant, which efficiently breaks down sarin; and the R variant, which breaks down other chemicals but not sarin. People have two copies of the gene in their DNA, resulting in three possible combinations: QQ, QR, or RR.

Researchers randomly selected 1,116 Gulf War veterans for the study, half of whom had GWI symptoms and half of whom did not. They collected blood and DNA samples from each veteran and asked whether the veterans had heard chemical nerve gas alarms sound during their deployments.

The study found that those with the weakest form of the PON1 gene were significantly more likely to have Gulf War Illness.

Researchers said their study did not rule out the possibility that other chemical exposures could have caused a small number of GWI cases, but that the study adds to existing confidence that sarin is a causative agent.

A ‘Forgotten Generation’

For decades, Gulf War illness has been misunderstood or even ignored by medical professionals and federal authorities, leading to intense frustration for veterans.

“The first Gulf War veterans are like a forgotten generation,” Kaitlin Chacon, an Air Force veteran and research coordinator at a Stanford neuroscience lab, told Coffee or Die Magazine. “They’re sandwiched in between Vietnam veterans and also OIF veterans, which were very intense, combative campaigns […] and they were not informed about the toxic things they were exposed to for a very long time.”

A 1997 congressional investigation found the DOD and VA were not interested in finding a cause for GWI, did not listen to sick veterans’ concerns, and consistently blamed symptoms on post-traumatic stress or other psychological conditions. The House Committee on Government Reform and Oversight characterized the federal government as “content to presume the Gulf War produced no delayed casualties, and determined to shift the burden of proof onto sick veterans.”

“Sadly, when it comes to diagnosis, treatment and research for Gulf War veterans, we find the Federal Government too often has a tin ear, a cold heart and a closed mind,” the report reads.

But the problem persisted, and in 2013, former VA epidemiologist Steven Coughlin testified to Congress that the VA had hidden or manipulated research findings that would have validated Gulf War illness as a neurological condition.

While the DOD eventually acknowledged that those suffering from the chronic and undiagnosed illnesses were likely exposed to multiple chemical agents while overseas, affected veterans struggled for years to obtain VA benefits.

The VA previously estimated that 44% of veterans who served in the Persian Gulf War had medical issues commonly referred to as Gulf War illness, and that those deployed to Southwest Asia in the years since may suffer from similar issues, according to the Government Accountability Office.

However, the GAO found the VA denied about 83% of the 102,000 Gulf War illness claims it received between 2010 and 2015. The approval rate for GWI was about three times lower than for all other medical issues, the GAO wrote in its 2017 report.

“Gulf War Illness is not always well understood by VA staff,” GAO researchers wrote in the report, and suggested medical examiners could benefit from training on the illness.

Haley’s latest study was funded by the DOD and VA. He said he hoped the findings would accelerate the search for better treatment.

But Chacon, who is currently running a study on using neurostimulation to alleviate pain associated with GWI, cautioned that veterans should not expect immediate real-life impacts following the publication of new findings. She emphasized that the process of conducting studies, replicating the research, and reaching the stage where physicians can act on findings is extremely slow. But the research can be extremely meaningful for veterans who have suffered for years from unexplained illness.

“I see my patients break down in tears when they finally are validated that they do have a legitimate illness due to being in the Gulf region,” she said. “It’s very cathartic.”

Read Next:

Hannah Ray Lambert is a former staff writer for Coffee or Die who previously covered everything from murder trials to high school trap shooting teams. She spent several months getting tear gassed during the 2020-2021 civil unrest in Portland, Oregon. When she’s not working, Hannah enjoys hiking, reading, and talking about authors and books on her podcast Between Lewis and Lovecraft.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.