We Won’t Be King: What One of Sean Connery’s Finest Films Tells Us About Afghanistan

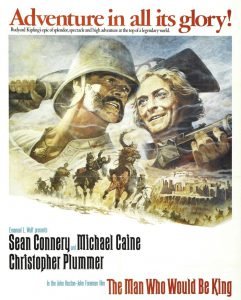

Sean Connery starred in the 1975 John Huston social commentary, The Man Who Would Be King.

Hours after Sean Connery died on Saturday, I watched The Man Who Would Be King because I’d heard it was a masterpiece. And as a veteran of the war in Afghanistan, I wanted to see what the film could tell me about the country whose land I fought over.

The 1975 John Huston film tells the story of two British soldiers — Daniel Dravot, played by Connery, and Peachy Carnehan, played by Michael Caine — who desert their post in India to set themselves up as kings in Kafiristan — known today as Nuristan — a land in northeastern Afghanistan where no white man had set foot since Alexander the Great.

After 19 years of American occupation in Afghanistan, the Taliban and Afghan government are now attempting to negotiate a peace deal, but violent attacks have marred the process and don’t bode well for the country’s future. The outcome of America’s adventure in Afghanistan may have been predictable for any student of history familiar with Afghanistan’s punishing terrain and reputation as “the graveyard of empires.” Before the US invaded the country, the Soviet Union famously withdrew from Afghanistan in 1989 after a long, bloody conflict.

Based on a short story by Rudyard Kipling, The Man Who Would Be King is set in the late 19th century. In the film, Christopher Plummer plays Kipling, a journalist who is destined to tell the story of the duo’s epic adventure.

Dravot and Carnehan are military lifers who decide to leverage their experience with imperialism and profit from their expertise. They venture over the Hindu Kush mountains armed with 20 rifles and great ambition. When they reach their target, the soldiers make good with some local Afghans by repelling an attack from a neighboring tribe. The duo offers their services to the friendly tribe and quickly wins hearts and minds. Dravot becomes elevated by the tribe to the position of a deity after he is wounded by an arrow in battle that draws no blood. He becomes the biggest foreign experience to hit northeastern Afghanistan since Alexander the Great.

Dravot and Carnehan are shown the wealth of Kafiristan and are told by the leading spiritual elder that they may take anything they wish. Caine figures they can’t hump the loot out until springtime — several months away — when the weather will be manageable for crossing the Hindu Kush. This affords enough time for Dravot’s power to go to his head.

The principal actors’ roles as lifers are comedic and believable, perhaps because both were veterans. Connery served a stint in the Queen’s Navy during the Cold War, and Caine deployed to the Korean War as a soldier in the Queen’s Army.

Dravot explains to his loyal subjects of Kafiristan that all they need to succeed in battle is to master close-order drill and stop thinking. Kipling’s social commentary is timeless and especially resonates with me as I reflect on my time in northeastern Afghanistan.

My Marine infantry unit helicoptered into the Korengal Valley as the first outside occupiers to attempt it. Alexander the Great never made it that far, and our insertion was only possible because of helicopters. I remember the Taliban’s radio chatter reporting our insertion, hard stares from old farmers who didn’t appear impressed with our presence, and walking into an ambush during an exhausting patrol. The terrain was unforgiving, and I expected hairy fighting to follow soon. Several years after I left, our forces eventually withdrew from the area because the mountains made it expensive to resupply and impossible for outsiders to defend.

The Man Who Would Be King was shot in Morocco, but a mud complex and shallow stream in the film looked eerily similar to the landscape I remember. My unit deployed into the Korengal Valley hoping to expand our influence. Unlike in the film, there were no riches or wealth for us to plunder. My short deployment into the valley turned into a waiting game between US forces and the locals. We saw some violence, but the heat would really turn up for the units who stuck around longer and remained after us.

Eventually, Connery and Caine’s fictional characters were driven out of the area by the locals, just like the British Army, the Soviets, and the United States. It was all a helluva story nonetheless.

Garrett Anderson is a writer and filmmaker in Portland, Oregon. As a Marine rifleman, Anderson fought in the second Battle of Fallujah in Iraq and later in Afghanistan’s Korengal Valley. He is writer, director and producer of The November War, a documentary about a squad of Marines on one of their worst days in the Battle of Fallujah.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.