Sebastian Junger on ‘Freedom,’ Leaving War Behind, and Afghanistan Exit

Sebastian Junger. Photo by Ethan E. Rocke.

In 1997, Sebastian Junger achieved commercial and literary success with The Perfect Storm, the bestselling book that helped launch his storied career in adventure journalism. He followed his breakout success with an impressive list of nonfiction books, articles, and documentary films, cementing his place as one of the best contemporary nonfiction storytellers.

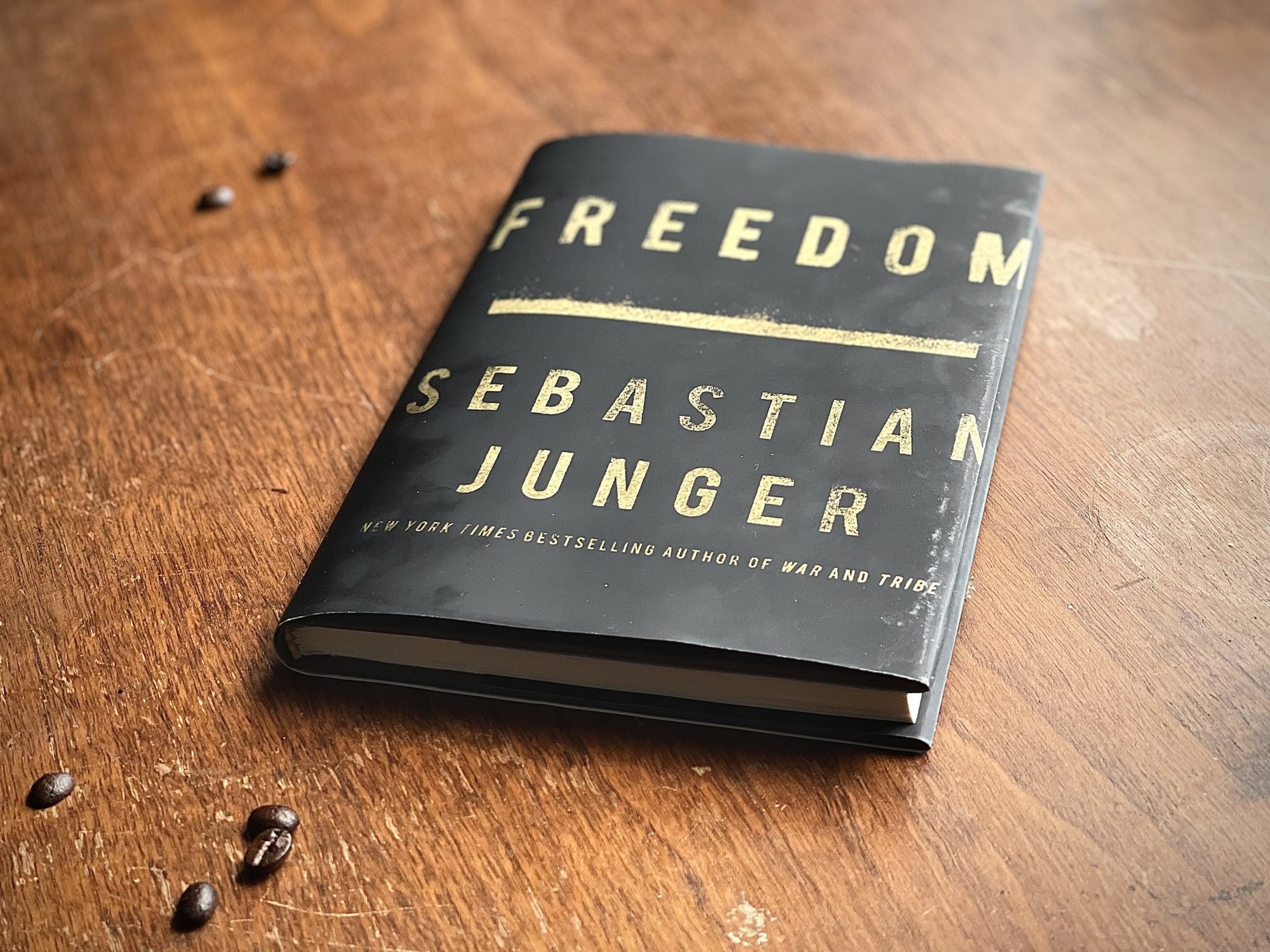

His most recent book, Freedom, challenges what that word really means in modern society. After illegally walking along nearly 400 miles of railroad and researching ways in which different cultures view freedom, Junger thinks he’s figured it out. Coffee or Die Magazine sat down with him to discuss the upcoming book, the US apparently leaving Afghanistan, and Junger’s creative inspiration.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You’ve been a conflict journalist for decades now. War has been a major theme in your work. What made you step back from war for Freedom?

You know, I had a couple of close calls out there. Then, just weeks after the Oscars [Junger and Tim Hetherington were nominated for a 2011 Oscar for their documentary Restrepo], we were supposed to go on assignment to cover the Libyan civil war, and at the last minute, I couldn’t go. Tim went on his own and was killed in the city of Misrata, a little over 10 years ago now. So I saw the effect of his death on his family and on me, and on my wife at the time who was really close to him. I mean I watched everyone get just annihilated. I realized, you’re really not gambling with your life; you’re gambling with everyone else’s lives. And so I stopped. I have two young children, so now it’s not even a remote possibility that I would go overseas for something like that. I don’t even want to be separated from them — forget about risking my life! But also, war is repetitive. I feel like I’ve understood what I was hoping to understand about it and about myself in war. I wouldn’t have been learning anything new, and there was a lot of other stuff to learn about, so I moved on.

What do you hope people will take away from Freedom?

Freedom is a very misused word. People sort of dragoon it into service for all kinds of absurd political ends, but it is a core human value and it’s something that only humans really have access to. I came to find through my research that throughout millennia, humans have maintained their autonomy from greater powers by three main methods: They can run away, they can fight, and eventually, they have to outthink them. So Freedom is divided into three sections: “Run,” “Fight,” “Think.” I wanted people to appreciate how desperate many people are for freedom and how raw and physical the fight for freedom sometimes is. In a healthy democracy, it doesn’t come down to that, because the laws have codified people’s freedoms in an adequate way. Democratic rights are very recent, and the freedom question has been relevant for at least 100,000 years.

Between people’s reservations toward getting vaccinated, mandates about wearing masks, and social restrictions, Americans are increasingly divided over COVID-19 and the government’s response to it. How can your exploration of American ideals around freedom inform the conversation?

I think people have to be realistic. If you accept the aid, support, and protection of a group — in this case, the US government — you have to abide by the rules it has devised to run society safely. For example, you can’t just say, “It’s my right to run red lights.” I mean, you could do that, but it’s not a right. It’s a crime. And it’s not up to you to decide what are rights and what are crimes. Rights are not self-given, rights are conferred by a group for all the individuals. So when people talk about “freedom,” what they really mean are their rights. That is something decided on collectively by society. If you’re going to be part of this huge, affluent, and often privileged collective, you have to abide by its norms or contest them in court and get the laws changed. I mean, it’s not that there isn’t recourse, but it has nothing to do with your personal rights.

Freedom seems to be an expansion of your documentary The Last Patrol. How does the book differ from the film?

It was years [after the film] that I decided I would write a book about freedom, and I cast my mind around when I was at my most free. Again, it depends how you define it, but by some definitions, I was at my most free walking for 400 miles along the railroad lines when, on most nights, we were the only people who knew where we were.

That kind of physical freedom often comes with an awful lot of physical suffering, hardship, and exertion. It was not easy out there, so in some ways, we were not free at all. We were all carrying 70 pounds — often in great heat. Whether you’re free or not often depends on how you define it. The more comfortable and safe you are, the more dependent you are on the society around you, and the less free you are in that other sense of being unconstrained by rules. You are constrained by rules; you are part of society, which is why you’re comfortable and safe. The less comfortable and safe you are is a whole other kind of oppression, but you’re free from social constraint. So it’s sort of like pick your poison. You cannot be both completely free and completely safe at the same time. It’s impossible.

You covered the war in Afghanistan expansively for decades. Since that war had such an obvious impact on your life and work, how do you feel about America’s (apparent) final withdrawal this year?

Well, you know everything has an upside and a downside. The upside to withdrawing is the last 2,000 American troops are not in any risk of dying if they aren’t in Afghanistan, obviously. The downside of withdrawing those last few people is that Afghanistan is at real risk of being overrun by the Taliban, and the Afghan people will once again be subjected to their extremely harsh and inhuman Islamic laws. I’ve been going to Afghanistan since 1996, and it’s a country and a people I am extremely fond of, and the idea that they will cycle back into another civil war and a state run by the Taliban is just appalling to think about. As a friend of mine said, “Journalists don’t tell people what to think, they tell people what to think about.” So that’s what I would advise people to think about in terms of our withdrawal. We’re setting up the same conditions that gave rise to the Taliban and al Qaeda there in the first place. It doesn’t mean that will happen again, but it is the same conditions on the ground.

You’ve been compared to Hemingway for your choice of topics and your writing style. Who are some of your literary inspirations?

I definitely grew up reading Hemingway. I hitchhiked across America reading Hemingway. Joan Didion I think is amazing. Jill Lepore is pretty extraordinary; she’s an amazing scholar and writer. As I was sort of becoming a writer, I absolutely adored Barry Lopez and Peter Matthiessen, and John McPhee for classic nonfiction. There are so many great writers, but those are some of the primary ones.

Coffee or Die is owned by a coffee company, so I’ve got to ask: How do you take your coffee?

A lot of cream and sugar! I pretend it’s dessert.

Read Next: In ‘Freedom,’ Sebastian Junger Says US May Be on a Collision Course With Itself

Mac Caltrider is a senior staff writer for Coffee or Die Magazine. He served in the US Marine Corps and is a former police officer. Caltrider earned his bachelor’s degree in history and now reads anything he can get his hands on. He is also the creator of Pipes & Pages, a site intended to increase readership among enlisted troops. Caltrider spends most of his time reading, writing, and waging a one-man war against premature hair loss.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.