U.S. bombs pummeled the Baghdad skyline in in the opening salvo of the invasion. Screenshot of CNN coverage of the Iraq invasion.

Cable television was an intermittent luxury during my childhood. Options for visual entertainment were normally limited to the five stations you could pick up via antenna, watching ants on the sidewalk, and the three Playboys I found in my dad’s old army bags in the basement. Twenty-four-hour cable news wasn’t among my options.

So, on March 19, 2003, I had no choice but to head down to the local Kmart to catch the invasion of Iraq. No one knew that this wasn’t going to be over in a few weeks like the last go-round; rather, it would wax and wane for the next 16 years (and counting) and claim the lives of over 4,500 Americans (and counting).

As a sophomore in high school, I was too green to participate in the latest American effort to replace a dictator who decided not to play along. I was actually worried that I was going to miss my generation’s war, that I would be too old by the time the next one came around … that I would never have a chance to prove my loyalty to the greatest nation on earth in the fires of battle. I figured I was doomed to be like the boomers born in ’55: looking like they were old enough to fight in Vietnam but not reaching enlistment age until after the war ended.

Fortunately, the U.S. military had embraced a robust embed program for journalists who wanted to ride along in the sprint to Baghdad. This, coupled with the brave media crews who pre-positioned themselves in Baghdad, allowed Americans to watch the invasion of Iraq live on TV. Say what you want about the media, but it takes a big pair of brass ones to go sit on top of a building with a camera in a city that is about to get bombed into the stone age.

So, there I stood, Barq’s root beer in hand, staring at about 20 television sets in the Kmart electronics section, all tuned to CNN. The talking heads weighed in with their hot take on how it would all go down, with a little box showing a live feed of the Baghdad skyline at night in the corner of the screen. They said the military was planning to go with a “shock and awe” strategy, meaning the coalition of the willing would swoop in with such ferocity that the Iraqi military would have no choice but to throw down their weapons and surrender, sealing a swift victory for the good guys. Sounds fucking badass if you ask me.

Little did I know that men I would call close friends later in life were at that moment racing over the Kuwait border in tanks, trucks, and armored personnel carriers, screaming through the air toward Baghdad in blacked-out bombers and readying themselves for a daring parachute jump into airfields in western and northern Iraq. Little did I know that there would be no swift victory, that I would indeed get my chance to fight in Iraq — three times, in fact — that six years later I would stand on an Iraqi airfield waiting to deliver news of a fallen Ranger to his best friends, days after a status of forces agreement (SOFA) was put in place.

Just as my attention (and excitement) was starting to wane, the wall of TV’s lit up with the opening salvo of Operation Iraqi Freedom. There I was, my 16-year-old eyes glued to a wall o’ war with an unhealthy level of red, white, and fuck-you coursing through my veins. It was shock and awe in all its anticipated glory. It was amazing in every sense of the word.

In retrospect, my excitement for the start of a war and the death of fellow humans seems grotesquely masturbatory. But for a teenage boy with his heart set on joining the U.S. Army, it was a spectacle to behold.

Long gone were the days of waiting for the nightly news to catch a few clips of America’s far-off wars. Now war could be consumed live and unfiltered, making me feel somehow connected to the events happening a world away. It wasn’t just Boeing, Raytheon, and the like who could profit off war these days — the 24-hour cable networks (who often decry the use of force) could get a slice of that oh-so-lucrative pie, too.

After the shock wore off and the awe started to fade, I made my way back through the maze of aisles bathed in fluorescent lights and out to my car in the near-empty Kmart parking lot. I was excited that America was showing Saddam Hussein who was boss and jealous of the men and women who were in on the action to take an evil man down. I hoped they could get to the bad guys before any of the WMD’s were launched at them — or at us here in America. There was a lot at stake, after all.

Ultimately, those matters were out of my control, as they were for most Americans. So, I popped in the new CD my cousin burned for this occasion and pumped up the volume on Outkast’s “Bombs Over Baghdad” for my short drive home.

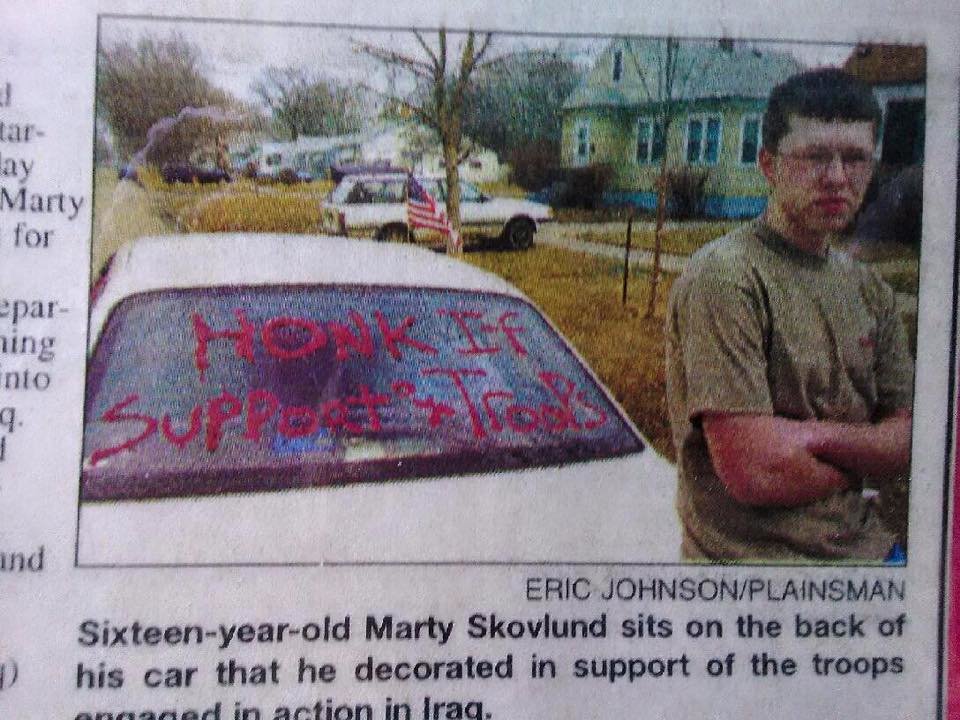

Marty Skovlund Jr. was the executive editor of Coffee or Die. As a journalist, Marty has covered the Standing Rock protest in North Dakota, embedded with American special operation forces in Afghanistan, and broken stories about the first females to make it through infantry training and Ranger selection. He has also published two books, appeared as a co-host on History Channel’s JFK Declassified, and produced multiple award-winning independent films.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.