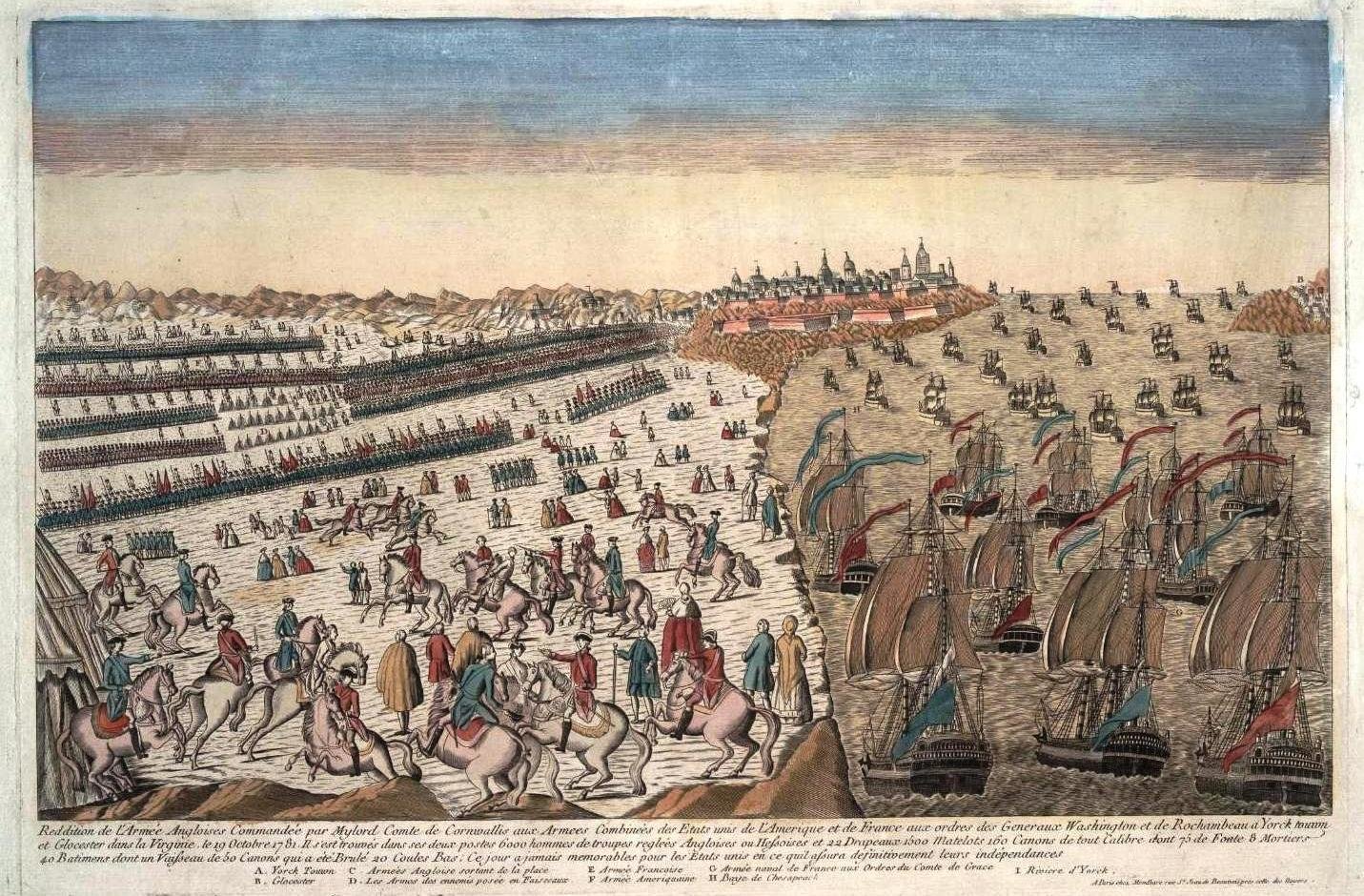

The Siege of Yorktown is considered the last major battle of the American Revolution. Wikimedia Commons image.

In the early evening of Oct. 14, 1781, a force of approximately 800 American and French soldiers armed with muskets, bayonets, axes, and swords stood ready for battle on the outskirts of Yorktown, Virginia. Once the signal was given, they would emerge from their siege trench and charge across an open field toward a network of British forts and defensive positions manned by some 8,000 troops.

As commander in chief of the Continental Army, Gen. George Washington would personally oversee the siege. The stakes were high. Days earlier, American and French artillery had bombarded numerous defensive garrisons called redoubts — small, enclosed earthen forts armed with cannons and mortars to defend Yorktown. Now only two of those garrisons, Redoubt 9 and Redoubt 10, remained standing. If Washington succeeded in capturing them, the victory would deal a heavy blow to British morale at a crucial moment in the war. But if they failed, America’s quest for independence would remain as precarious as ever and the war would grind on.

The American Revolution began in 1775 with battles in Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts. A rebellion of 13 American colonies against British rule erupted into a protracted armed conflict with multiple fronts. Skirmishes and battles were fought up and down the East Coast for several years, and then the French got involved beyond just providing arms and supplies to the Americans, signing the so-called Treaty of Alliance in 1778. Without French reinforcements, the rebels stood little chance of winning the war.

Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau, an officer with the French expeditionary force, arrived in Newport, Rhode Island, in the summer of 1780 to aid the Americans in their rebellion. British forces were then largely concentrated on two fronts: Gen. Henry Clinton’s forces in New York City and Gen. Charles Cornwallis’ forces in the South. Rochambeau and Washington held several meetings that winter to coordinate a strategy for the upcoming year. They devised a plan for their combined armies to attack Clinton with the expectation that the French fleet would reach New York in time for the offensive. But when Rochambeau linked up with Washington outside the city in July, he learned the French fleet had instead sailed to the lower Chesapeake Bay. And so their plans shifted.

The revised strategy would begin with an elaborate diversion. Washington would create the illusion that the Continental Army was planning to attack New York. To that end, he ordered large camps with massive brick bread ovens to be erected near Clinton’s garrison. He also prepared fake battle plans with the assumption that they’d end up in the hands of British intelligence. Then, in mid-August, he ordered a skeleton crew to remain in New York while the rest of his forces joined Rochambeau in a march 450 miles south to the Virginia coast.

By the end of September, an estimated 17,600 American and French soldiers had gathered in Williamsburg. Cornwallis, whose army in Yorktown totaled 8,000 troops, sent an urgent request for help to Clinton, who responded with a promise of 5,000 reinforcements to arrive by sea no later than Oct. 5. But those reinforcements would never arrive, as the French navy had just defeated the British in the Battle of the Chesapeake and the bay was now firmly under French control.

In early October, American and French artillery units pounded Cornwallis’ fortress complex, firing on average 1,700 munitions per day, with the hope of forcing a quick surrender. Washington himself fired the first round, from an American siege cannon. The round reportedly ripped through a home and killed two British officers. On Oct. 11, a second siege line took form within 400 yards of Redoubt 9 and Redoubt 10. After an initial attack on the forts was rebuffed by British defenses, Washington ordered a surprise nighttime assault to be carried out three days later.

On Oct. 14, 1781, the American and French coalition was split in half to assault the two redoubts: 400 French troops would storm one, while 400 Americans raided the other. That evening, at approximately 7 p.m., the attack began.

Some of the Americans wielded axes to break up abatis and fraises, sharp wooden obstacles designed to stop infantry advancements, while others hacked through the fortress walls. British defenders, severely outnumbered, fired their rifles frantically at the oncoming horde. Capt. Stephen Olney, a commander with 1st Rhode Island Regiment and veteran of numerous battles, reached the top of the fortress and immediately engaged in hand-to-hand combat, parrying British bayonets with his spontoon spear. More Americans scaled the ramparts to join Olney as the British defenders hurled grenades in an attempt to stop their advances. Lt. Col. John Laurens, of South Carolina, led a detachment of approximately 80 men to intercept fleeing British troops. Laurens surrounded the remaining British, and the redcoats threw down their weapons and surrendered.

Both redoubts were taken within less than 30 minutes. The Americans lost nine soldiers and several more were wounded, including Olney, who had been bayoneted in the leg and stomach. In addition to the American casualties, 15 French soldiers were reportedly killed. The British lost a total of eight men. Five days later, Cornwallis surrendered.

Despite having some 30,000 troops at seaports in New York, Charles Town, and Savannah, their defeat at Yorktown was crushing enough to cause the British to finally abandon hope of winning the war. The lurking presence of the French fleet and the heavy losses they suffered in the Battle of the Chesapeake deterred the British from conducting future maritime attacks. In the two years following the Siege of Yorktown, which is considered by historians to be the last major engagement of the American Revolution, British Prime Minister Frederick North and his administration were ousted from power and the new government made overtures to the Americans. Washington’s reputation, bolstered by his victory at Yorktown, gave him ample clout in the negotiations that culminated in the Treaty of Paris.

The American demands included four main conditions: independence from Great Britain and the removal of all British troops from American soil, a clearly defined US border, a reversion of Canadian territory back to the conditions set by the Quebec Act, and American rights to fish in the Grand Banks. On Sept. 3, the signatures of British and American representatives inked the Treaty of Paris, and thus the United States of America was officially born.

This is the first article in a series dedicated to spotlighting the last major engagements of American conflicts.

Read Next: Knowlton’s Rangers: America’s 1st Organized Intelligence Unit

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.