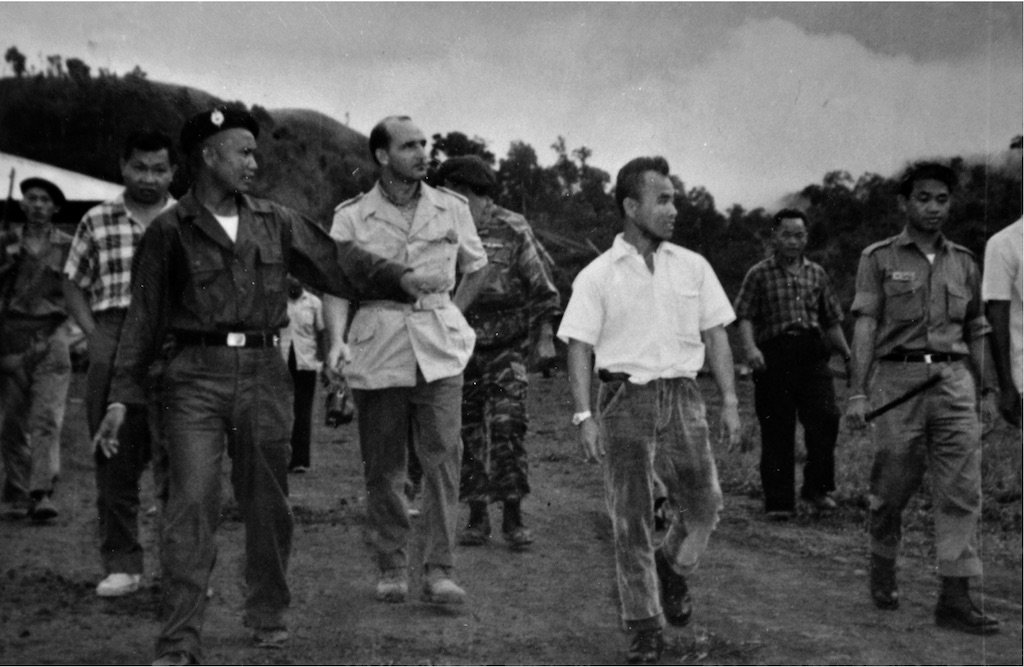

Laotians trained by CIA in Smokejumping gear. Photo courtesy of the National Smokejumpers Association (NSA).

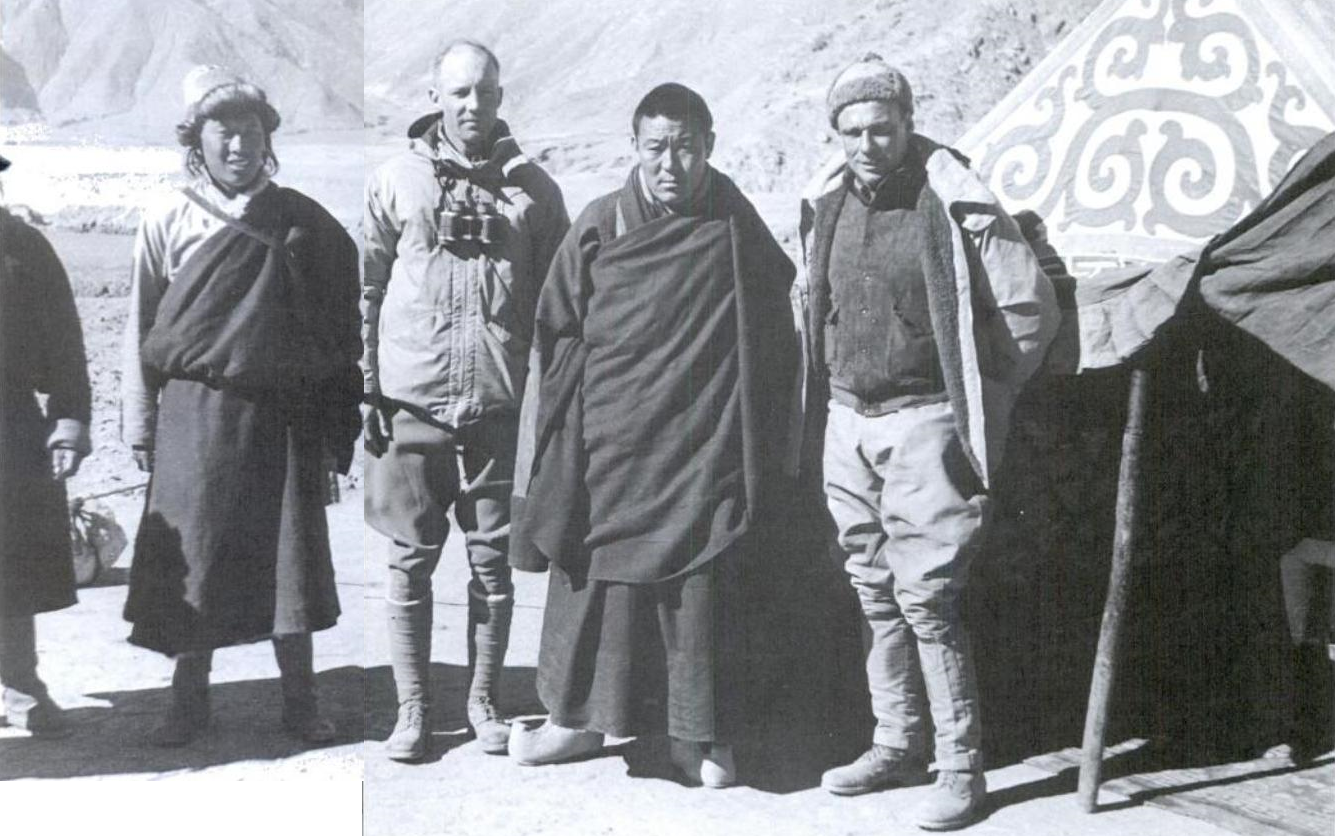

The CIA had its eye on Tibet. The Buddhist nation of vast plateaus and mountain ranges in Central Asia was completely isolated from the rest of society. A diplomatic relationship with the small country surrounded by China on three of its sides was of utmost importance. On a mission from President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, two Office of Strategic Services (OSS) officers, Capt. Brooke Dolan and Maj. Ilia Tolstoy, traveled through India to Tibet in September 1942 to contact the Dalai Lama, then just 7 years old.

Following the conclusion of World War II, the OSS was disbanded and re-formed as the Central Intelligence Agency in 1947. Only two years later, the CIA watched its new ally from afar and monitored the increased hostilities of Mao Zedong, the founding father of the People’s Republic of China. Mao had threatened to “liberate” Tibet, a strong-armed escalation to retake the government from the Dalai Lama.

In a contested intensification of force, the Chinese military marched through the Himalayas toward Chamdo, the third-largest city in the eastern part of the Tibet Autonomous Region. On May 23, 1951, China forced Tibet to sign a peace treaty called the 17-Point Agreement — declaring its autonomy as long as China oversaw its foreign policy including the civil and military components. If Tibet hadn’t signed the “agreement,” the action would have been a death sentence.

The young Dalai Lama had his hands tied. Without outside help, his nation’s independence was under threat. The staff types and officers at the CIA with covers as diplomats began searching for a hardy group who had special training in remote and mountainous areas.

The US military had previously established a relationship during World War II with the US Forest Service (USFS). US Army paratroopers from the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions participated in an exchange program with the smokejumpers — an elite firefighting force that parachutes from planes into isolated areas to fight forest fires. The all-Black paratroopers chosen became known as the Triple Nickles, and they were trained to prevent the spread of fires caused by Japanese balloon bombs.

Instead of training airborne paratroopers as the military did before, the CIA contracted smokejumpers who already had all the necessary knowledge in terrain, reconnaissance, weather, and a variety of other critically important skills. Smokejumpers go through their own selection course to get to their units; the CIA could choose from the very best in their ranks.

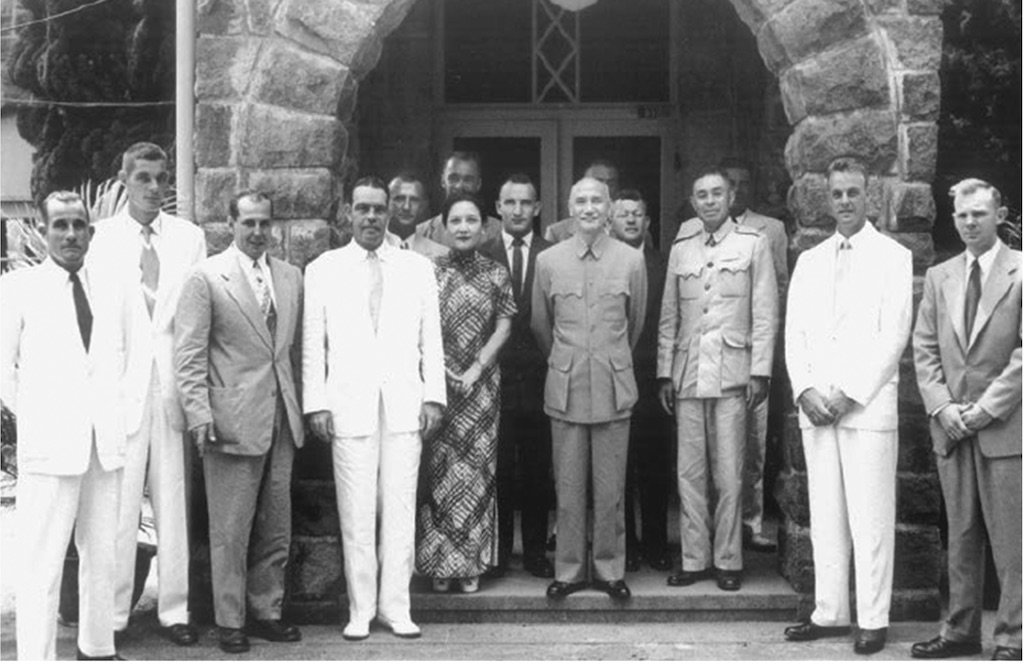

Garfield Thorsrud was a Missoula, Montana, smokejumper tasked with training two CIA officers at the Nine Mile training facility in Montana in 1951. The CIA recruited Thorsrud and six other smokejumpers on a covert operation in Taiwan to train Nationalist Chinese paratroopers to facilitate personnel and cargo drops over mainland China. From 1957 to 1960, however, this covert relationship between the smokejumpers and the CIA went global.

More than 100 smokejumpers were sworn to secrecy on behalf of the US government. Ray “Beas” Beasley, a former Air Force winter survival expert who trained aircrews in airborne operations in Libya and the Korean War, was called upon in multiple capacities.

“We were training air crews for Africa and Ivy Leaguers for the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA),” Beasley told Smokejumper Magazine. “Those Ivy Leaguers thought they were special, but they didn’t know a goddamned thing. It was truly unbelievable.”

Smokejumpers, including Beasley, acted as “kickers” or jumpmasters who “kicked” out 10,000 pounds of weapons, ammunition, and equipment to Tibetan resistance forces at elevations as high as 14,000 feet. The pilots from the CIA’s Civil Air Transport (CAT) flew sorties using old China Air Transport civilian routes in C-130B planes across Tibet to arm Khampa guerillas. The first pass dropped the agents, and the second dropped the pallets of supplies. These operations also trained as many as 200 Tibetan commandos at Camp Hale in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado to jump alongside CIA officers.

“We were always ‘Romeo,’” Beasley told the Great Falls Tribune in 2014, referring to the call sign for their mission. “When we did these jobs, it was in the full moon and we flew right by Everest.”

When the Dalai Lama fled Tibet to India in 1959, the CIA kickers rigged a yellow parachute to a pallet filled with 300,000 rupees. As the Dalai Lama was in exile, the CIA funded $1.7 million per year to support Tibet’s resistance against Chinese and Soviet Union influence.

After Tibet, Beasley participated in covert operations in the “secret war” in Laos as well as the Bay of Pigs invasion. During the 1960s, if the CIA was running an operation inside a country they weren’t supposed to be in, flying unmarked aircraft, the smokejumpers often towed along. The smokejumpers’ roles expanded beyond jumpmaster duties to acting as liaison and operations officers in Guatemala, the Congo, India, Guam, Indonesia, and even the Arctic.

Thorsrud and five other smokejumpers dressed in parkas participated in Project Coldfeet, which premiered the ingenious Fulton surface-to-air recovery system (STARS) or Skyhook: The passing plane intercepts a 500-foot line with a smokejumper attached and yanks him into the air to retrieve him. Project Coldfeet was an intelligence-gathering mission at an abandoned Soviet Arctic drifting ice station — and the CIA deemed the mission a success.

The smokejumpers’ clandestine service with the CIA and their heroism was kept in the shadows. David W. Bevan was killed on Aug. 31, 1961, when his Air America C-46 plane crashed into a Laotian mountaintop. The former smokejumper’s mission remained a secret for 56 years, and not even his family were aware of how he had died. In 2017, the CIA publicly acknowledged Bevan and other CIA operations officers with a star on its memorial wall. At that time, there were 125 stars. Since 2019, the wall has grown to 133 stars, some of which honor those whose identity remains classified.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.