Hunting Season: What I Learned From Witnessing a Sniper’s Head Shot

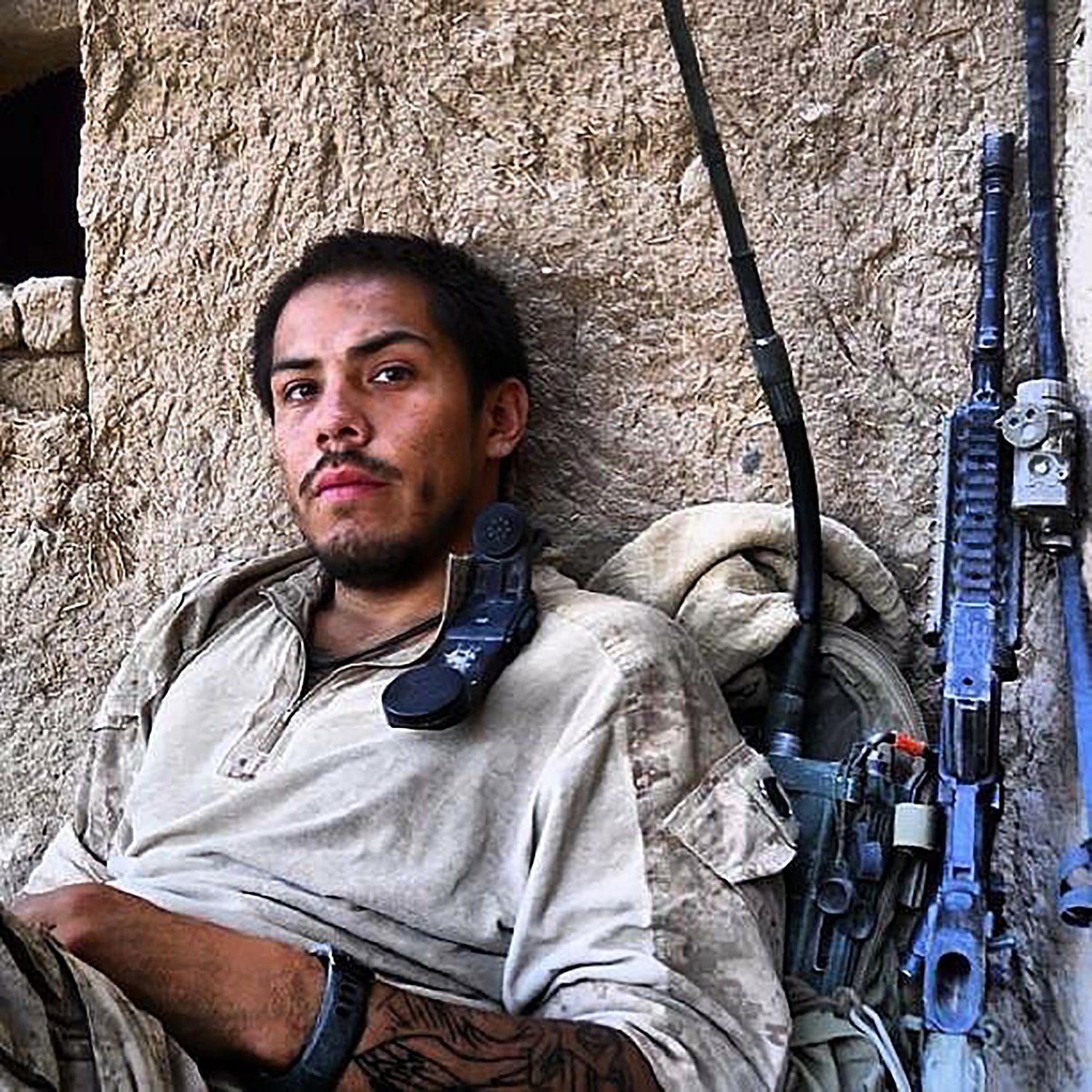

Green Zone North. Photo courtesy of G.C. Briones III.

Sunrise over southern Afghanistan. Colors of orange, red, blue spreading up from the horizon line with the morning call to prayer, the muezzin’s voice intoned through loudspeakers, resounding over the valley, over the fields and orchards, the winding canals, the trees, the river, the cloistered villages that harbor the insurgents who watch our every move. So begins another day of hunting the Taliban. The war resumes, like clockwork, never getting old.

More than five months in Sangin. Still alive, still breathing, still living out of a rucksack that holds only the essentials: water, emergency chow, ammo, a triage kit, a PRC-117 radio, socks, an iPod, a point-and-shoot camera, dip, cigarettes. I have found a certain comfort in the rhythm of preparing for patrols, a ritual that involves troubleshooting and synchronizing all of the platoon’s radio equipment. As the comms chief for Charlie 3, ensuring seamless communication between the various teams that make up the platoon is one of my primary responsibilities.

Nighttime patrols entail occupying local compounds, paying the families not to leave, and taking great care to ensure that their neighbors don’t find out we’re there. Under the cover of darkness, we convert their homes into hiding sites. We smash holes through the walls, which we call “murder holes,” to increase our vantage points. We fill sandbags to the brim and use them to build fighting positions on the roof. By dawn the compound has been renovated into Hotel del Sangin, a well-furnished and fortified observation post directly inside the hornet’s nest.

The author monitors communications with battalion headquarters following an all-night patrol in the vicinity of Sangin. Photo courtesy of G.C. Briones III.

Flat-roofed huts made of clay and reinforced with stones, tree branches, and rope lie strung along the valley amid a landscape of verdant farmland and rocky desert. The Helmand River snakes through the western portion of the valley, forming a convenient corridor for insurgents and drug smugglers. The Marines occupy a string of outposts on the east side of the valley, where the land rises along Highway 611, providing us with a clear view of the lush no man’s land between us and the Taliban-controlled banks of the river, an area we call the “green zone.”

In this war between the Marines and the Taliban there are no rules of engagement. It is a game, a blood sport, not played by the rich and their vast armies, but by small factions of bloodstained men, men like myself and my comrades. Officially, we are the Marine Corps’ 1st Reconnaissance Battalion. But to the Taliban, we are no longer Marines; we are the sons of Satan. They call us the “black diamonds,” because of the distinctive black diamond-shaped mounts on our helmets. The nickname has followed us around Helmand province ever since we took Trek Nawa on June 16, 2010.

The Taliban’s tactics were different in Trek Nawa than they are now, several months later. The insurgents are better organized, more disciplined, and more determined, apt to carry out complex ambushes that rupture the rural silence with a finely tuned orchestra of rifles, mortars, and rocket-propelled grenades.

The day will forever be ingrained in my memory, like the birthday of one of my children.

October 10.

The day will forever be ingrained in my memory, like the birthday of one of my children. As usual, my company occupies the high ground, our patrol base situated along Highway 611 overlooking the green zone. Smoke rises from a burn pit dug in one corner of the compound, infusing the crisp morning air with odors of human piss and shit, melting plastic, and vaporized chemicals. Since sunrise, we have been taking small-arms fire from multiple directions. A Taliban sniper holed up somewhere to the southwest is providing the insurgents with effective cover fire, allowing them to move freely through the green zone.

While the Marines manning the rooftops exchange sporadic gunfire with the enemy, I sit on the clay steps outside the radio operations center, preparing my morning meal — a nutrient-dense chicken noodle MRE, replete with crackers, cheese spread, and a touch of Tabasco sauce. Behind me there is chatter coming from a speaker box connected to a PRC-117 inside the ROC. The two Marines on the southwest rooftop — Joe and Al — are going back and forth with the officer in charge, explaining to him that they still haven’t located the sniper.

The sniper seems to have realized that Joe and Al can’t see the muzzle flashes from his rifle, as his fire is becoming more frequent. This only increases the need to pinpoint his location, forcing the two Marines to expose themselves more and more as they attempt to draw him out, teasing him with their lives.

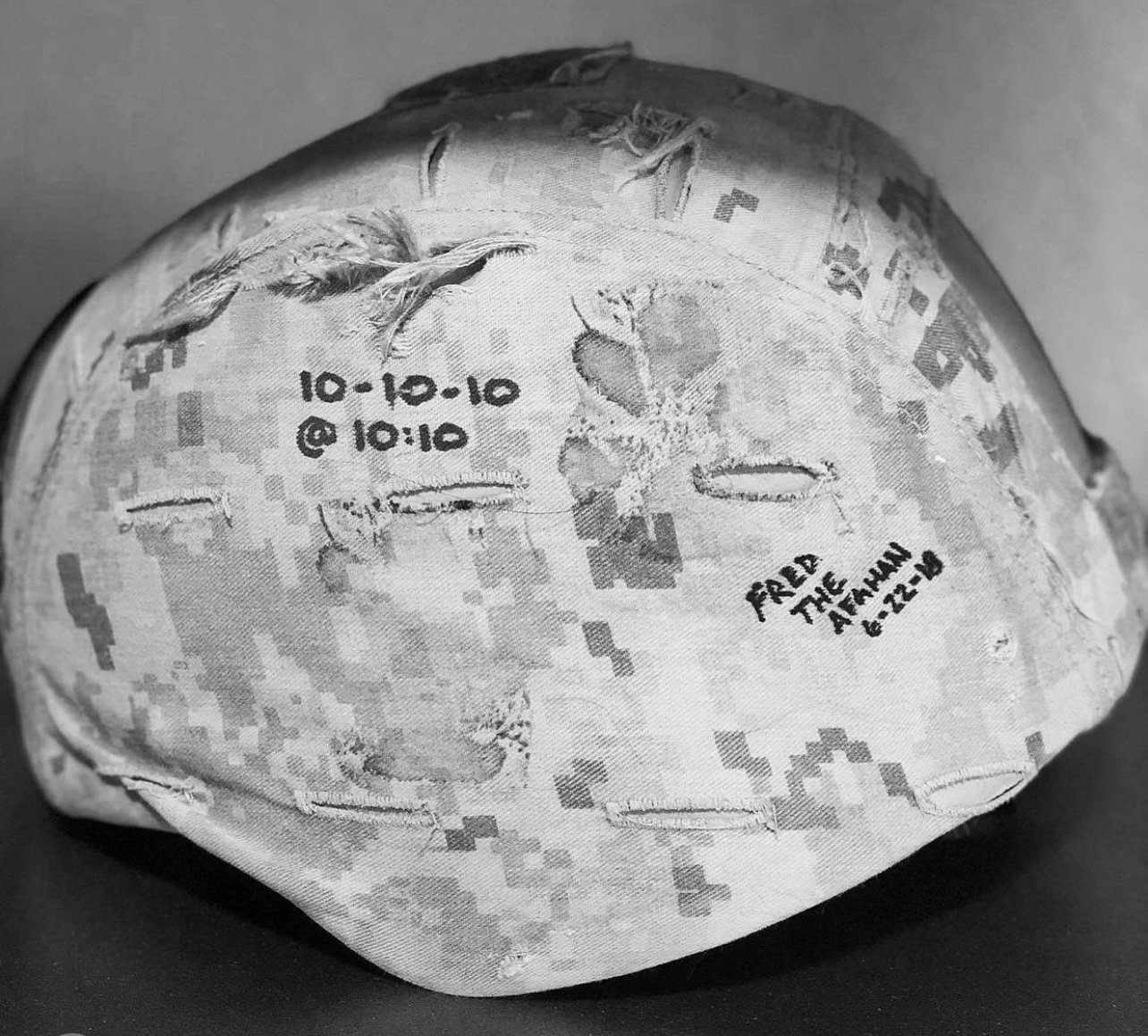

Joe’s helmet shows where the sniper round entered and is marked with the date and time of the incident. Photo courtesy of G.C. Briones III.

I first met Joe in Iraq in 2008, when I transferred from Alpha Company to Charlie. Since I was the communications chief for Charlie 3 and Joe was a radio telephone operator, I got to know him well both personally and professionally. Like me, he took his job seriously and embraced the concept drilled into all of us that a Recon team’s success is contingent on three criteria: ability to shoot, ability to move, and ability to communicate. He possessed a special type of grit, one that can only be acquired through pain and suffering. He was a smart motherfucker, a Recon Marine through and through — tall, muscular, a lady’s man, with a square jaw that could take a punch (I know from experience). As an RTO, his toughness and analytical mind served him well. When it came to operating and troubleshooting a radio under extreme loads of stress, he was able to maintain his composure and channel the comm gods to create strong wavelengths through the atmosphere.

Now, listening to his voice over the stretchy sound of the speaker box, I can tell that Joe is annoyed with the officer in charge, who keeps pushing for the sniper’s location. “If we get our heads any higher, we are dead,” Joe says matter-of-factly.

Capt. Hardhead doesn’t reply. Looking over my shoulder, I see him seated on an MRE box, scribbling in a notepad. Then I look up at the rooftop where Joe and Al are busy trying to locate the sniper. Constructed from sandbags stacked in a square about 3 or 4 feet high, the fighting position offers a 360-degree view of the entire Sangin River Valley. From where I sit, I can see Joe looking through his binoculars, his helmet clearly exposed above the sandbags.

SLAP! A bullet impacts the sandbag just to the side of Joe and sand goes flying. He ducks down for a moment, then raises his head back up, a little lower than before. Al comes over the radio: “Sniper fire directly south.” His voice is calm and even, but I know that his heart is beating faster than a hummingbird’s wings. Mine is too. There is also the tingling in my fingers, the tightness in my chest, the uncontrollable thoughts and emotions, the familiar surge of energy that runs through my body whenever it feels death coming close.

I feel like I’m trudging through quicksand as I run toward Joe’s position. I’m fully expecting to find him dead.

SMACK! Another sniper round drills into the sandbags, this one a little closer to Joe than the one before. Al grabs the back of Joe’s bulletproof vest and yanks him down. Joe returns to the wall with his binoculars, adjusting his position so that he is crouched down even lower than before, but his helmet is still fully exposed. Then I hear a SNAP! and Joe’s head slams sideways as if struck by a baseball bat.

The first thing I hear next is a crack in the speaker box, then Al’s voice, shouting, “Joe’s been shot!”

Everyone around me freezes and remains frozen for a few heartbeats.

I hear myself shouting for a corpsman, and the sound of my own voice brings me back to reality. My cries are echoed by the Marine in charge of base security. “Doc!” he yells, like a wolf howling for help. Then I watch two of our corpsmen jump into action, adrenaline coursing through their veins. I drop my unfinished MRE on the floor, grab my helmet, and run after them. My heart is in my throat. Suddenly the world is pervaded by a sense of doom. I didn’t expect to wake up this morning and watch my brother get shot in the head. I know he didn’t either.

A security post used by the Marines of 1st Reconnaissance Battalion in their daily fight against Taliban insurgents in the Afghan district of Sangin. Photo courtesy of G.C. Briones III.

I feel like I’m trudging through quicksand as I run toward Joe’s position. I’m fully expecting to find him dead. In my head I see his lifeless body slumped over, blood all over, pure chaos. But that is not the scene I see materializing before me as I approach the base of the security post. Nope. Instead, I see Joe looking frazzled and lost at the top of the ladder as he tries to find his way off the roof. Along with a few other Marines, I grab hold of Joe’s arms and body and help lower him down.

Joe is alive and breathing. It turns out that the bullet that struck him had traveled through the suppressor attached to his M40A5 before piercing his helmet. Stripped of force, the round shredded, but did not penetrate, the helmet’s inner bulletproof material and sliced the side of Joe’s scalp. It was a minor flesh wound, but the bullet’s impact also unleashed a shock wave of energy through Joe’s brain, causing a high-grade concussion. He spent a week recovering in the rear before he was cleared to return to Charlie Company and resume hunting the Taliban.

Twelve years later, I find myself still trying to unpack the lessons of that day. I have come to realize that seeing Joe survive such a close brush with death was a gift in some ways — a rare gift among those of us who play this blood sport. During my time as a Recon Marine, my mind had become conditioned to expect the worst possible outcome in every situation, but in telling this story I am reminded that I don’t have to see the world that way.

Maybe it will always be in my nature to plan for the worst, but at least now I know that it is not unreasonable to hope for the best.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2022 edition of Coffee or Die’s print magazine as "Hunting Season."

Read Next: The End of War Brings Mixed Emotions — So, How Are You Feeling?

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.