US Army Sniper vs. US Marine Scout Sniper — Who’s the Sharpest Shooter?

The origin of the American sniper is vague, with reports dating back as early as the American Revolution. The first established peacetime sniper school within the U.S. military was the U.S. Marine Corps Scout Sniper course in Quantico, Virginia, in 1977. The U.S. Army followed suit with their sniper school at Fort Benning, Georgia, in 1985. Brotherly competition between the two branches is infamous and continuous, predating the establishment of peace time training for snipers.

As far as sniper legends go, the Marine Corps has Carlos Hathcock, aka White Feather, with 93 confirmed kills during the Vietnam War. Of the Viet Cong enemies he eliminated, several were known for their brutality — including a woman known as “Apache.” According to Military.com, “‘She tortured [a Marine she had captured] all afternoon, half the next day,’ Hathcock recalls. ‘I was by the wire… He walked out, died right by the wire.’ Apache skinned the private, cut off his eyelids, removed his fingernails, and then castrated him before letting him go. Hathcock attempted to save him, but he was too late.”

On the U.S. Army’s side is Adelbert Waldron, also a legendary Vietnam War sniper, with 109 confirmed kills. After serving 12 years in the U.S. Navy, Adelbert joined the Army, starting out as a buck sergeant and deployed to the Mekong Delta area. Major General Julian Ewell, commander of the 9th Infantry Division, recalled a story about Waldron’s eagle eye: “One afternoon he was riding along the Mekong River on a Tango boat when an enemy sniper on shore pecked away at the boat. While everyone else on board strained to find the antagonist, who was firing from the shoreline over 900 meters away, Sergeant Waldron took up his sniper rifle and picked off the Viet Cong out of the top of a coconut tree with one shot.”

Coffee or Die spoke with both Army snipers and Marine Scout Snipers about their professional differences.

Black Rifle Coffee Company’s Editor in Chief, Logan Stark, started his career in the Marine Corps in May 2007. He spent four years in the service and deployed three times.

Stark passed sniper indoctrination and, later, the Scout Sniper course. He said the most difficult part of the school was the actual shooting. It wasn’t standardized, 1,000-yard shots on paper, but shots from 750 to 1,000 yards on steel. Their range was elevated, which made calculating wind calls for their shots more difficult.

“You get these swirling winds coming off of the mountains, mixing with the wind coming off of the ocean, which makes reading wind extremely difficult to do,” Stark said, adding that “suffer patiently and patiently suffer” was a saying they often clung to during training.

However, the difficult conditions are what helped them hone in on the skill set Marine Scout Snipers are expected to perfect — which is, according to Stark, being an individual who can rapidly and calmly process information and execute a decision off that assessment.

“That’s why I joined the Marine Corps, was to do stuff exactly like that,” he said. “There wasn’t a worst part — it was fun.”

While Stark never worked directly with Army snipers, he has learned through the sniper community that the major difference is “the reconnaissance element to the Marine Corps Scout Sniper program. We’re meant to be an independent unit with four guys going out on their own without any direct support.”

Phillip Velayo spent 10 and a half years in a Marine Corps Scout Sniper platoon. He passed the Scout Sniper course on his second attempt and was an instructor from 2015 to 2018. Velayo now works as the training director for Gunwerks Long Range University.

Velayo has worked with Army snipers in the past and from talking with them, he learned that the Army’s sniper school is shorter — five weeks — compared to the Marine Corps’ school, which includes a three-week indoctrination course in addition to the 79-day Scout Sniper basic course. He added that he believes Army snipers place more emphasis on marksmanship than on mission planning because the Army has designated scouts, whereas Marine Corps snipers are responsible for shooting and scouting.

Velayo presented an example: If you take a blank-slate Marine and put him through Scout Sniper school and do the same with a soldier on the Army side, he said, “I mean, you’re splitting nails at that point, but honestly, I’m going to give it to the Marine side that we hold a higher standard to marksmanship than Army guys.”

Brady Cervantes spent the better part of a decade, starting back in 2006, with the Marine Corps as a Scout Sniper, and deployed four times. Cervantes passed the Scout Sniper school on his second attempt after his first try was cut short due to family matters that pulled him out of class.

“One thing I do respect about the Army is that they have certain calibers of curriculum that we may not,” Cervantes said, regarding differences between the two sniper schools, adding that the Army possibly goes into more depth as far as mission focus for a sniper. However, he said that he believes the Marine Corps maintains the highest standard within the military’s sniper community.

Cervantes said that if you take any Marine Scout Sniper and place them in a different sniper section, their shooter-spotter dialogue is uniform so they can function seamlessly as a team. In Cervantes’ experience overseas, the Army sniper teams he was around didn’t appear to have a clear-cut dialogue between their shooters and spotters.

But at the end of the day, Cervantes said, “if you’re a brother of the bolt, you have my respect.”

Ted Giunta served in the U.S. Army’s 2nd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment from 2003 to 2009, transferring to the sniper platoon in 2006. He deployed four times as a sniper, three of those as the sniper section leader. Since leaving the military, he has been working with the U.S. Department of Energy, specifically pertaining to nuclear transportation. He is one of the two long-gun trainers for his entire agency.

Giunta attended the U.S. Army Special Operation Target Interdiction Course (SOTIC). He believes that the Marine Scout Sniper program and the Army Sniper program are similar in how they train and evaluate their candidates. SOTIC, on the other hand, was a “gentleman’s course,” where they weren’t smoked or beaten down but evaluated on whether they could do the job or not.

Giunta said comparing Marine Scout Snipers to 75th Ranger Regiment snipers comes down to the level of financing for the unit. Because his unit and their mission set was Tier 2 and often worked with Tier 1 units, they had better access to training and equipment, which gives them the edge over Marine Scout Snipers. Giunta said the work as a sniper is an art form, and no matter what branch you are in, you make it your life.

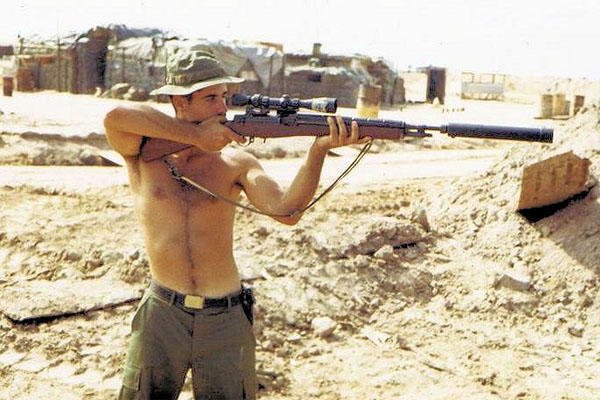

Andrew Wiscombe served in the U.S. Army from 2005 to 2010, deploying to forward operating base (FOB) Mamuhdiyah, Iraq, from 2008 to 2009 as part of the scout sniper team.

Wiscombe said that Army snipers who belong to a dedicated sniper/recon section are comparable to Marine Scout Snipers. As far as a soldier who goes through the basic sniper school and then returns to an infantry line unit where they aren’t continually using their skills, they won’t be on the same level, he said.

The biggest difference Wiscombe is aware of relates to how they calculate shooting formulas. “I know we use meters and they use yards, so formulas will be slightly different,” he said. “The banter may be different, but the fundamentals remain the same for any sniper. At the end of the day, there is some inter-service rivalry fun and jokes, but I saw nothing but mutual respect for very proficient shooters and spotters all around.”

Jaime Koopman spent eight years in an Army sniper section, from 2008 to 2016. He has worked with Marine Scout Snipers several times in a sniper capacity; he also had two Marine Scout Sniper veterans in his section after they switched over to the Army. Koopman worked alongside the Marine Scout Sniper veterans as well as others while competing in the U.S. Army Special Operations Command (USASOC) International Sniper Competition.

Koopman’s experience with Marine Scout Snipers showed him that their training is a little different from Army snipers, but it’s comparable. “The Marine Corps Scout Sniper is an MOS for them, so the school is longer, affording them the opportunity to dive a little deeper in each subject area,” he said, “whereas an Army sniper is expected to gain the deeper knowledge outside the school house with his section.”

As far as the most recent standings from the 2019 USASOC International Sniper Competition, first and second place positions were held by U.S. Army Special Operations Command (USASOC) teams while third place was claimed by a Marine Scout Sniper team. The 2020 competition has been postponed due to COVID-19 restrictions.

Joshua Skovlund is a former staff writer for Coffee or Die. He covered the 75th anniversary of D-Day in France, multinational military exercises in Germany, and civil unrest during the 2020 riots in Minneapolis. Born and raised in small-town South Dakota, he grew up playing football and soccer before serving as a forward observer in the US Army. After leaving the service, he worked as a personal trainer while earning his paramedic license. After five years as in paramedicine, he transitioned to a career in multimedia journalism. Joshua is married with two children.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.