The Harrowing True Story of a US Soldier Who Was Shot 13 Times

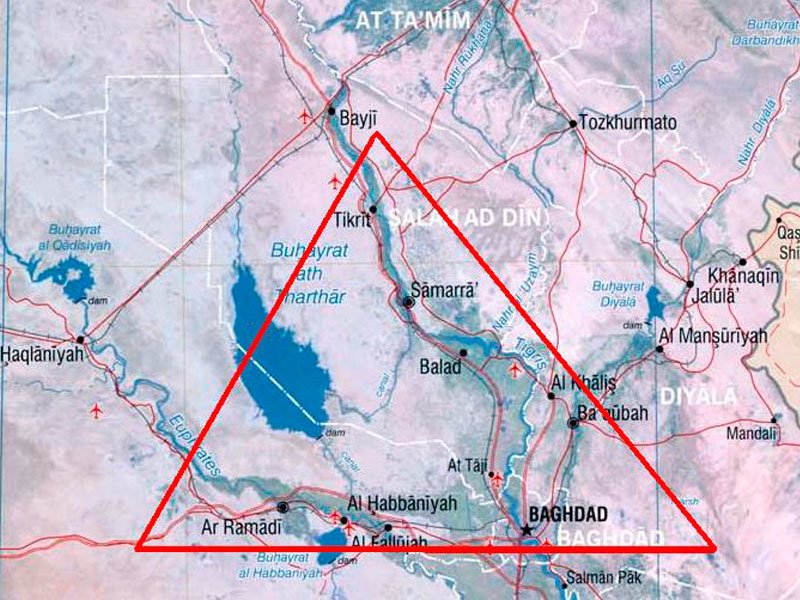

U.S. Army Specialist Jay Strobino was with his team in Rushdi Mullah, a small farming village in Iraq’s infamous Triangle of Death, on Feb. 1, 2006. They were there on a mission to grab a suspected enemy insurgent. Everything was going according to plan as they searched the house — no surprises.

That all changed when a truck full of insurgents rolled into the opposite side of town and pinned down a corner of their outer cordon. Strobino was about to be in the firefight of his life.

Strobino, along with three others, made their way to the corner. He killed one of the insurgents who was trying to make it across the road; the resulting break in fire allowed him and his team to run across the street, closer to where the other enemy combatants were.

His team snuck behind a row of houses, where Strobino shot another insurgent through a window of an adjacent house. They then moved to the house that the remainder of the insurgents were behind. With his SAW gunner on the rooftop of the last building, Strobino and two others maneuvered to the back of the property.

Behind the house, there was a shed and a fence surrounded by bushes. Strobino was the first to scale it but not without some difficulty.

“When I got over, I saw two insurgents spaced about 10 to 15 feet apart, facing away from me. I held my aim but didn’t want to fire because everyone else I shot that day wouldn’t die, and we were taking up to 15 rounds to stop [them from] advancing or firing,” he said. Insurgents in Iraq were known to take drugs before going into battle that would often allow them to keep fighting even after suffering mortal wounds.

So he stayed put for the moment, waiting on his teammate to get over the fence, but his teammate kept getting caught. The two insurgents Strobino had zeroed in on turned to face him, and he was forced to fire. Fortunately, his squad leader soon made it over the fence and was able to join in the fight.

There was still another insurgent left, though. He was aiming his AK-47 around the front corner of the house, firing back at Strobino and his squad leader. In response, his squad leader threw a grenade, and their team followed after.

“I ran to the front corner of the building and peered around. His weapon was up and out of the front doorway. I put my weapon on burst and turned the corner, hoping to grab his barrel,” he said.

The enemy fighter heard them coming and had already started moving toward Strobino and his other teammates when he came around the corner. Strobino pulled the trigger, sending the target to the floor; however, the target fired back.

Strobino was hit, and it was bad.

“My leg was broken and my ulnar nerve was hit in my arm,” he said, “and I lost control of my right hand.”

The two soldiers with him had taken cover behind a truck, and Strobino planned to throw a grenade. But the moment he pulled it out, the insurgent threw his own over the truck where his team was positioned and came out firing. He sprayed his weapon again, hitting Strobino a second time.

“At this point, I thought everyone was dead and I was immobilized. But my squad leader called out my name — I couldn’t believe it. I threw my grenade over to him so he could arm it and toss it around the corner,” Strobino said.

But the grenade didn’t kill the insurgent, and with his condition quickly deteriorating, getting Strobino out of there became the priority. The other members of his team pulled him behind the building. His platoon sergeant and his radiotelephone operator (RTO) moved up, bandaged him, pulled security, and called for a medevac.

‘I lost a large portion of my right femur and couldn’t walk on that leg for six months.’

The insurgent was still in the house. A second team threw multiple grenades into the home before going in. Two of those soldiers took rounds; one of them died on the medevac back to Baghdad. After that, they called in Apaches to finish the job, blowing up the house.

Strobino’s condition was so dire that his parents were nearly summoned in fear that he wouldn’t make it home. He immediately went under the knife and had surgeries every 12 to 24 hours. From Iraq, he was flown to Germany for two weeks and eventually back to the U.S., where a long road of recovery awaited him.

Strobino had been shot a total of 13 times, and it cost him more than just blood. “I lost a large portion of my right femur and couldn’t walk on that leg for six months,” Strobino said. “I lost a lot of that quad group as well.”

He had to teach his brain how to perform small physical tasks again. He got winded standing at the side of his bed while two people held him. Fortunately, the great people at places like the VA hospital in Augusta, Georgia, and the Fisher House helped him pull through.

“The Fisher House is like a Ronald McDonald house for wounded vets,” Strobino said. “It’s practically five-star accommodations for the family members of a wounded veteran that are recovering at the adjacent hospital. The family has their own private room. There’s a huge shared kitchen, laundry room, dining rooms, relaxing rooms. Everything is handicap accessible. And the families stay there free of charge.

“It helps the veteran because they can have family there while they are trying to recover,” he continued. “And it also helps the families because they are living in an area with other families going through similar situations. They can all empathize and help each other out.”

“Surround yourself with positive people and feed off each other’s energy. Know that you’re not going to be able to do it alone, and it’s not going to be easy.”

At the end of 2006, Strobino was awarded a Silver Star for his valor in combat. The citation reads:

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress July 9, 1918 (amended by an act of July 25, 1963), takes pleasure in presenting the Silver Star to Specialist Jay Christopher Strobino, United States Army, for exceptionally meritorious achievement and exemplary service as a Team Leader in 3d Platoon, Bravo Company, 1st Battalion, 502d Infantry Regiment, 2d Brigade Combat Team, 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault), attached to the 4th Infantry Division, during combat operations in support of Operation IRAQI FREEDOM, on a mission on 1 February 2006 in Rushdi Mulla, Iraq. Specialist Strobino’s exceptional dedication to mission accomplishment, tactical and technical competence, and unparalleled ability to perform under fire and while injured, contributed immeasurably to the success of his unit in Rushdi Mulla, Iraq, and reflects great credit upon himself, his unit, the 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) and the United States Army.

“The absolute biggest thing is to stay positive,” he said, in regard to facing an unexpected challenge. “Surround yourself with positive people and feed off each other’s energy. Know that you’re not going to be able to do it alone, and it’s not going to be easy. But be sure to celebrate each small victory.”

Justen Charters is a contributing editor for Coffee or Die Magazine. Justen was previously at Independent-Journal Review (IJ Review) for four years, where his articles were responsible for over 150 million page views, serving in various positions from content specialist to viral content editor. He currently resides in Utah with his wife and daughter.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.