This 1972 stamp from the Soviet Union commemorated the Soviet space program. Wikimedia Commons image.

With the Cold War raging and the Soviets securing victory after victory in the Space Race, America’s CIA wasn’t sitting on the sidelines. The Soviet Union’s space technology was beating America’s in just about every appreciable way, and America’s intelligence agencies were working overtime to monitor and decipher data spilling out of Soviet rockets as they poured into the sky. It was a time of uncertainty–and perhaps even a bit of desperation–for the burgeoning superpower that was America in the 1950s. So, when a Soviet Lunar satellite was sent out on a global tour to parade their successes before the world, it offered a unique opportunity for the CIA to hijack the satellite for a bit of research while it was still firmly planted on the ground.

From our vantage point in the 21st century, we have a habit of looking back on the Space Race as though America’s ultimate victory was a sure thing. After all, in the decades that followed World War II, America was uniquely positioned to help rebuild the Western world, gaining diplomatic, economic, and military leverage around the globe and rapidly ascending to the lofty position of the planet’s only remaining superpower by the close of the century.

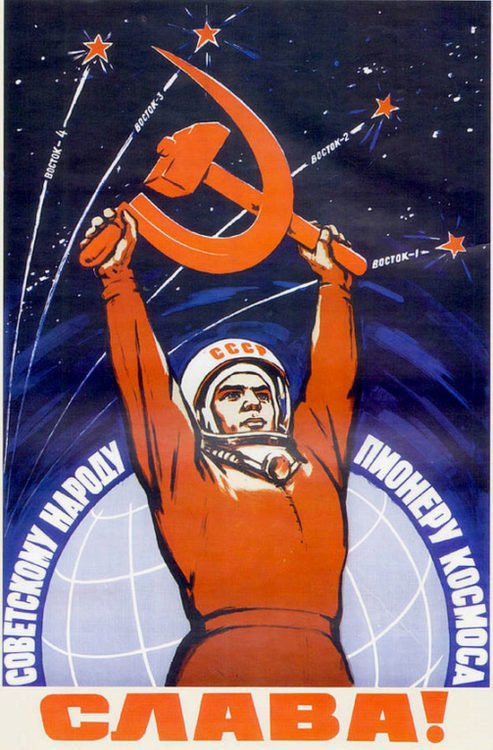

But the truth is, to paraphrase famed Marine general James Mattis, America had no pre-ordained right to victory in the Cold War, and perhaps least of all in the Space Race that ran in parallel to the America-Soviet military arms race of the day. The Soviet Union didn’t just beat America and the rest of the world into orbit with Sputnik in 1957, they proceeded to pummel the United States’ space efforts without mercy for years to come.

The Sputnik Crisis and Soviet space program supremacy

Let there be no mistake, the importance of Sputnik in terms of how it framed America’s contemporary perception of the Soviet threat, both military and ideological, can’t be overstated. Immediately following Sputnik’s beeping transmissions from low earth orbit, the United States, and indeed much of the Western world, plummeted into what has since come to be known as the “Sputnik Crisis.”

In no uncertain terms, early Soviet space program victories were seen by many around the globe as a clear argument in favor of the efficacy of the Soviet communist model of government and societal structure. With each subsequent win at the technological forefront of human reach, the Soviet Union wasn’t just proving what could be done through their approach to economics and policy, they were also demonstrating what America’s capitalism couldn’t do… or at least, couldn’t do as quickly.

That overarching fear that the communists were not only winning in terms of nuts and bolts but also in terms of hearts and minds directly led to the establishment of NASA, the reshuffling of resources toward rocket and orbital sciences, and of course, a flood of funding into both defense and prestige programs meant to offset the Soviet advantages that were becoming manifest on multiple fronts. In the New York Times alone, Sputnik 1 was mentioned in articles an average of 11 times a day between October 6 and October 31 of 1957, so pronounced was America’s general fear regarding the Soviets in space.

It didn’t get better from there. In November of 1957, the Soviet Union became the first nation to put a living animal in orbit with Sputnik 2 carrying Laika the dog. The following month, America made its first attempt to put a satellite into orbit with the Naval Research Laboratory’s Vanguard TV3 (Test Vehicle 3). The rocket made it approximately four feet off the launch platform before collapsing back down onto itself and exploding.

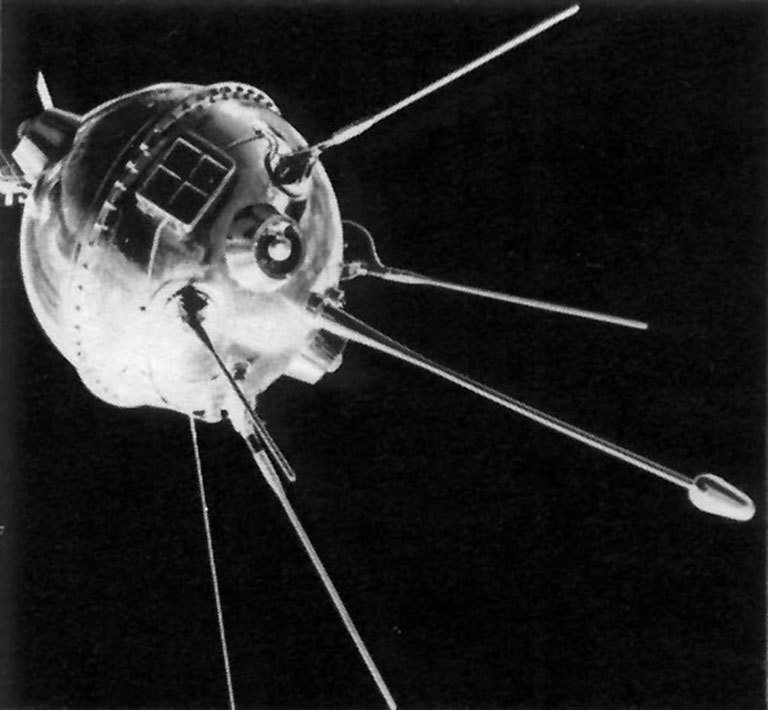

The following month, however, America would make it into space with Explorer 1, and later that year, NASA would replace the National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics (NACA) and help to steer the nation toward its eventual space supremacy–but that supremacy wasn’t to come for some time yet. In 1959, the technically failed Soviet Luna 1 rocket flew further than any platform before it, escaping the moon’s orbit and finally settling into orbit around the sun. Later that same year, the Soviets claimed yet another first with Luna 2; the first spacecraft ever to reach the surface of the moon.

Soon, Luna 3 would send back images of the moon’s surface from orbit and by 1960, the Soviets were the first to send animals (two dogs, Belka and Strelka) and plants into space and bring them back alive. Within just another year, they would secure their crowning achievement to that point: Putting an actual human being in space with Yuri Gagarin.

There was no doubt, no debate, and no uncertainty. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the Soviet Union wasn’t just leading the Space Race, it was dominating it. If America wanted to turn the tables on the Reds, they’d need a closer look at what they were packing under the hoods of their rockets.

How to plan a spacecraft heist

In 1959, the Soviet Union decided to leverage their recent technological victories for a little PR, choosing a number of technologies, vehicles, and equipment that represented the very cutting edge of Soviet advances for a traveling exhibit. You might expect that the Soviet Union would know better than to send their actual top-tier tech for what amounted to little more than a bit of show-and-tell, and the CIA thought so too … but with the Soviets continuing to extend their lead in space, the opportunity to take a closer look at the crown jewel of the exhibition, a Lunic spacecraft very similar to Luna 2, housed within a modified rocket upper stage, was simply too great.

After a few plain-clothes agents got as close as they could without drawing any suspicion, they were surprised to see that the spacecraft tucked away behind glass-covered cutaways in the rocket housing appeared to be the real deal. Declassified reports have a habit of sucking the humanity out of a situation, but one has to assume this revelation came with some open mouths, raised eyebrows, and perhaps even a bit of covert intelligence officer hand-wringing within the CIA when word reached Langley.

Immediately, plans began to form to get an even closer look at Lunic, but the Soviet’s seeming naivety in parading a real satellite around didn’t extend to the security at their exhibitions. Soldiers guarded the satellite at all times while on display, including during off-hours when the museums and exhibition halls housing it were closed. It seemed clear that accessing Lunic while it was on display would be practically impossible, so the CIA turned their attention to how it was transported from exhibition to exhibition.

While all of the items were transported from city to city by rail car (with accompanying guard), the CIA identified some vulnerability in the way each item was transported from each exhibition to that rail car. The items were simply placed in unassuming crates and loaded into trucks that would drive them to the train station for loading. This transition was not heavily monitored by Soviet security, with items arriving at the train at random intervals and little coordination between drivers and the train personnel to speak of. In fact, the guards at the rail depots weren’t even provided with a list of what deliveries to expect, perhaps as a part of compartmentalizing information, but it was this specific shortcoming in the Soviet security strategy most of all that granted the CIA the opportunity they needed.

Hijacking the Soviet space program is easier from the highway

Intelligence operatives are often thought of as superhuman, as though it takes a unique biology to be a truly successful spy. The truth, as history so often reveals, is that spies are most often regular people like the rest of us; superhuman not in capability, but arguably perhaps, in audacity.

When the night came to enact the CIA’s plan, the agents responsible were hopelessly lacking in James Bond-esque gadgets to assure victory. It began, quite simply, with agents in plain clothes following the crate containing Lunic out of an exhibition, looking intently for signs of supplemental Soviet security. Surprisingly, despite their air-tight security during showings, no guards manifested and it soon became clear that the unassuming box truck carrying a nondescript crate full of Soviet state secrets would be making its short trip to the train station utterly unaccompanied.

So as the truck approached its turn off toward the train station, the CIA simply pulled the vehicle over and escorted the driver to a nearby hotel. From there, an agent hopped in the driver’s seat and guided the truck into a nearby salvage yard that had been chosen specifically for the high walls intended to hide the interior scrap from the rest of the neighborhood. It was one of the most daring espionage capers of the Cold War, and certainly had the potential to ignite a conflict between the planet’s two nuclear powers … But at the point of execution, the best the CIA could muster was little more than a carjacking and a local junkyard. Sometimes, it really is audacity that makes all the difference.

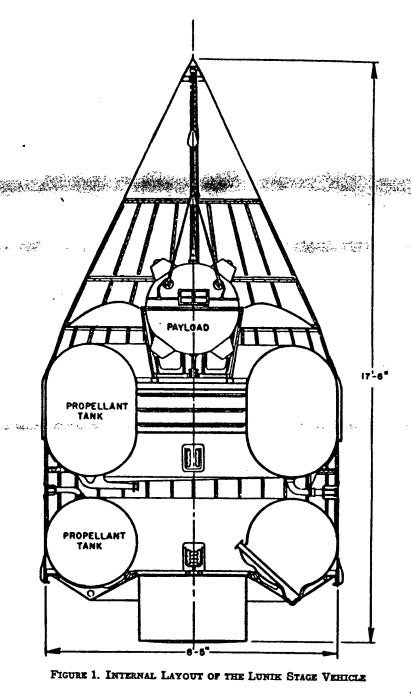

For 30 long minutes, CIA agents hovered in the shadows surrounding their freshly stolen truck, waiting for some sign that the Soviets had noticed Lunic’s absence. Once it seemed the coast was sufficiently clear, they descended upon the truck, and the 20 foot long, 11 foot wide, and 14 foot-deep crate housed inside. For their plan to work, it wasn’t enough to get to the satellite, disassemble it, and photograph what they could–they also had to re-assemble it, tuck it back inside its crate, and deliver it to the train station before morning, to keep the Soviets from knowing anything had even taken place.

Take off your shoes and hop in the rocket

To their relief, the crate itself had been re-used a number of times, making it fairly easy to open without leaving any clear signs of tampering. However, with no means to pull the rocket stage out of the crate, the team soon realized they’d have no choice but to do their work inside the wooden box. Agents took off their shoes and split into teams, climbing to the bottom of the crate using rope ladders they’d brought specifically for the job, and delicately removing hardware and panels to gain access to the secrets held within.

Soon, their plan hit a snag, however. The Lunic spacecraft wouldn’t be hard to access through the rocket stage it was housed in, but as they attempted to make entry, the CIA agents found a small, plastic seal with a Soviet logo emblazoned on it. In order to get to the spacecraft, the seal would have to be broken, but doing so would almost certainly reveal their meddling to Soviet authorities. Quickly, calls were made to CIA assets in the area, who assessed that they could replicate the seal and get their replacement to the salvage yard in time to re-assemble and return the rocket by morning.

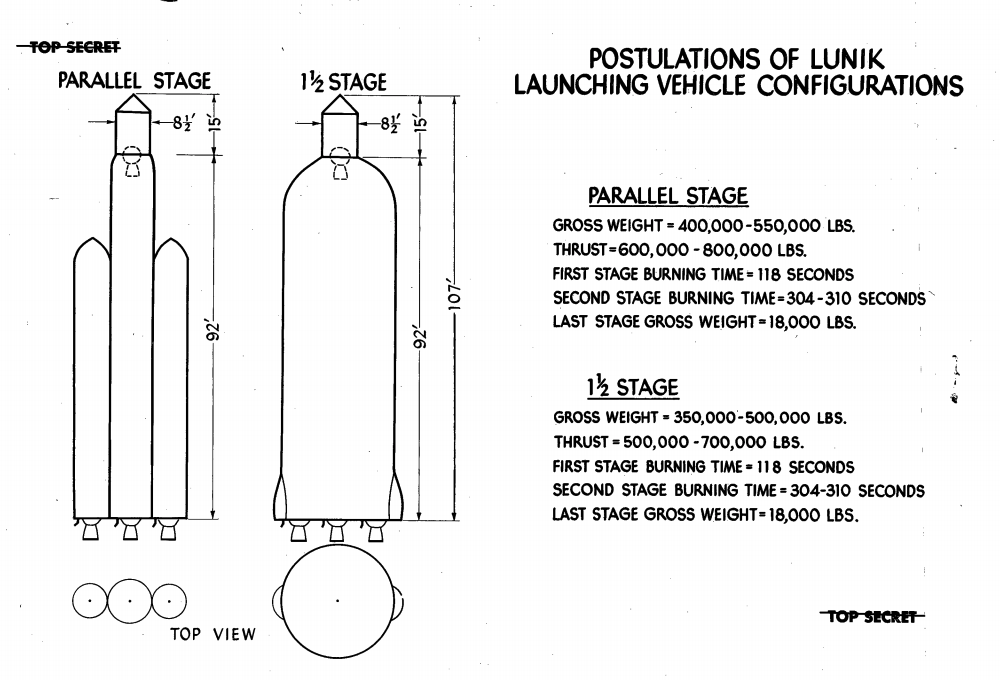

Although the engine had been removed, its mounts, as well as tanks for both fuel and the oxidizer remained, granting the CIA enough information to extrapolate the rocket’s engine size and payload capabilities. With the seal removed, Lunic itself was pulled out, prodded, disassembled, and photographed extensively. Information gleaned wasn’t only valuable from a design perspective, it also offered important context regarding the Soviet rocket program. Having measurements and weights recorded for a Luna 2-esque payload, the CIA would be able to make more sense of telemetry data they were gathering around each Soviet launch. It was a significant intelligence victory for the United States, and would go on to shape plans and policy regarding America’s own space efforts for years to come.

But getting the information was only part of the job. Getting it back unnoticed would require a similar degree of good luck and proper planning.

With the moonlight waning, CIA operatives working with hand tools and clad in their socks feverishly re-assembled Lunic and its rocket housing, adding the replica seal, removing their rope ladders, and re-securing the top of the crate. By 5 a.m., the original driver was reunited with his truck and payload, and he delivered it to the train station in time to beat the first guard’s arrival at 7 a.m.

The information gleaned from the operation gave America a fuller understanding of what the Soviet space program was capable of, which allowed them to plan their own efforts accordingly. No longer was America operating under the looming anxiety of the Sputnik Crisis without the real data they needed to make an honest assessment of the situation. And one could argue, it was in that newfound knowledge that America’s future space dominance would begin to sprout. In order to beat the enemy, you have to know where they are and what they can do… and the CIA learned more about that in the back of a stolen truck, with their shoes off and their flashlights on, than they had through the rest of their combined efforts to that point.

Less than 10 years later, the United States would declare victory in the Space Race when Apollo 11 landed on the moon right before a lander from the Soviet space program crashed into the other side. A bit more than 20 years after that, the Soviet Union would collapse, and the Cold War would officially come to an end.

This article was originally published on Sandboxx News. Follow Sandboxx News on Instagram.

Read Next: US Space Weapons: From Rail Guns to the ‘Rod From God’

Coffee or Die is Black Rifle Coffee Company’s online lifestyle magazine. Launched in June 2018, the magazine covers a variety of topics that generally focus on the people, places, or things that are interesting, entertaining, or informative to America’s coffee drinkers — often going to dangerous or austere locations to report those stories.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.