US soldiers. US army. US soldiers pray. Military of USA. Memorial day.

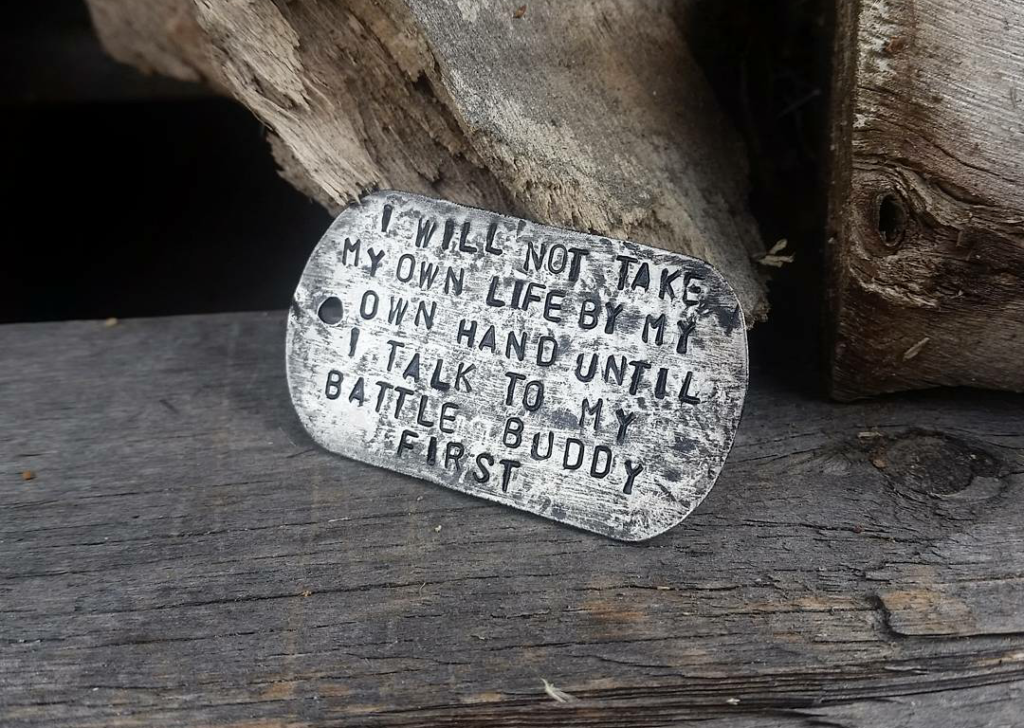

“I will not take my own life by my own hand until I talk to my battle buddy first. My mission is to find a mission to help my warfighter family.”

These words constitute the Spartan Pledge, a solemn oath meant to reverse the disturbing trend of suicide among veterans of the U.S. military and active duty personnel.

According the 2018 Annual Suicide Report released by the U.S. Department of Defense, 541 service members died by suicide in 2018, including 325 active duty troops. The data collected for this report show the suicide rate is 24.8 per 100,000 service members, up from 21.9 in 2017 and 18.7 in 2013. These 2018 numbers represent a six-year high.

Similarly, the 2019 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report published by the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs is bleak as well: 6,139 U.S. veterans took their own lives in 2017 — 16.8 per day, up from 5.9 in 2005. This rate is one and a half times that of the general (non-veteran) population.

In 2010, retired U.S. Army paratrooper Boone Cutler decided it was time to do something about these tragic statistics. Cutler came from a family with a long-standing tradition of military service. His father served in Vietnam, his grandfather in World War II. “My grandpa was actually the longest held POW in World War II,” Cutler said. “We take a lot of pride in that and give him a lot of respect. He was captured the day after the Pearl Harbor attack and was held from December 8 until the end of the war.”

Cutler was inspired to join the Army after learning about the U.S. invasion of Panama in 1989. “I remember the headline,” he said. “The 82nd Airborne Division had just jumped into Panama. I left home at 17 and joined the Army Airborne Infantry when I was 18. He later reclassed his military occupational specialty (MOS) and joined the psychological operations (PSYOP) community. Cutler deployed to Sadr City, Iraq, in 2005 as a PSYOP Team Sergeant. Serious orthopedic and traumatic brain injuries sent him to Walter Reed Army Medical Center for two years. While there, doctors told him he was suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a diagnosis he had no intention of accepting at the time.

The years that followed were difficult. Cutler was on several prescription drugs, and he grappled with violent outbursts and suicidal thoughts. In 2010, he was shocked to learn that he wasn’t alone. In a conversation with his closest “battle buddy” from Iraq, Cutler asked his friend if he’d ever considered suicide. “Every day,” his buddy answered.

6,139 U.S. veterans took their own lives in 2017 — 16.8 per day, up from 5.9 in 2005. This rate is one and a half times that of the general (non-veteran) population.

Holy fuck, thought Cutler. How could guys be so close on active duty — literally covering each others’ backs in a kinetic environment, know everything about each other, every hiccup, every burp, every fart … literally everything … and we don’t know this about each other after we come home?

Shortly thereafter, he called another friend who had been on his team. He discovered that teammate was struggling, too. He had been contemplating taking his own life and hadn’t left his home in two years. This was the genesis of the Spartan Pledge — a battle drill that, in Cutler’s words, helps warfighters “know what to do when they don’t know what to do.”

“We made an agreement,” Cutler said. “We knew we couldn’t actually stop each other from killing ourselves, but it was kind of a respect thing — if you’re going to do that, I can’t stop you. But don’t leave me spinning around on this planet for the rest of my life, wondering what happened and if there was something I could have done. Now [the pledge] is two sentences, but it literally started out as, ‘Motherfucker, you’d better call me.’”

Around this same time, Cutler learned about GallantFew, a then-new organization with a mission to help veterans in transition. GallantFew executive director Karl Monger soon became a close friend and mentor to Cutler. While talking on the phone, the topic of veteran suicide came up, and Cutler mentioned how he and his buddies were dealing with it. Monger stopped him mid-sentence. “Boone,” he said. “I think you’ve really got something there. This is something we should promote.” GallantFew began to introduce the pledge through its network, during one-on-one meetings with veterans in crisis. From there, it took root around the country and continued to grow organically.

A 2017 video, aptly titled “The Spartan Pledge,” featured commentary by Cutler and conversations with others who were inspired to “pay the pledge forward” in unique ways. Army veteran and Redcon-1 music artist Soldier Hard shared his idea to incorporate the pledge into his concerts. “Every warfighter knows about taking an oath,” he said. “We take oaths very seriously. Why not invite warfighters in the audience to come up on stage and take the Spartan Pledge?”

The video also featured U.S. Navy veteran and New York City firefighter Danny Prince, who told Cutler he wanted to honor the victims of 9/11 — those who died in the attacks, as well as our fallen military in the Global War on Terrorism. Prince had collected some steel from the World Trade Center wreckage. He and former U.S. Marine and commercial airline pilot Steve “Luker” Danyluk proposed to forge that steel into a commemorative sword. Two months later, the project was complete.

“Every warfighter who joined in this current era is there because of what happened at the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on 9/11,” Cutler said. “So we’ve come full circle now by creating a sword out of that tragic event that inspires people to live. That’s humbling. That’s something that touches your heart. When people touch that sword, it’s like connecting with all the souls that were lost.”

In 2011, Cutler launched a weekly talk radio show in the Reno, Nevada, area, called “Tipping Point with Boone Cutler,” which served as a platform for the former paratrooper’s raw, no-holds-barred style. That show aired through 2016. These days, Cutler spends his time spreading the word about the Spartan Pledge and connecting with his brothers and sisters in arms, both active duty and retired. “We’ve built a solid network from all walks of life,” he said. “We put our differences aside to save lives. It’s an amazing unifier.”

Cutler was a featured guest at the 2019 VetXpo conference in Dallas in October, which was sponsored by the GallantFew. His presentation, one of the many highlights of the weekend, was a spot-on snapshot of the state of the veteran community, the civilian world’s perception of warfighters, and why warfighters have such a challenging time with transition.

He shared his observation that, after Vietnam, Hollywood and the media habitually portrayed warfighters as “crazy vets.” As late as 2010, nearly half of all human resources managers said it was “difficult to hire” veterans due to PTSD — but they didn’t have a real understanding of PTSD. Cutler concluded that it was “PTSD phobia” that made it difficult to hire veterans, not PTSD itself. If PTSD was truly the problem, he continued, a woman who was raped or a person who lived through a natural disaster or a car wreck would also be difficult to hire. Yet, strangely, that did not seem to be the case — only veterans with PTSD posed this difficulty. Fortunately, due to advancements in mental health and organizations like GallantFew, the civilian population is beginning to understand PTSD, those affected by PTSD are talking about it more openly, and the associated phobias are fading.

As critical as he was of the civilian population, Cutler made it a point to hold his fellow warfighters accountable, too. He acknowledged that the transition to the civilian world is difficult, calling it a “different set of rules.” In the military, it is understood that everything can change and adjustments must be made. “If we’ve adjusted to those environments,” Cutler challenged the audience, “why are we so stubborn to adjust to this one?”

His answer was startlingly simple: At a time when most young people are learning to become independent — starting families, getting careers and making their own decisions — those who join the military are entering an authoritarian environment, in which they rely upon someone else, a squad leader, to tell them what to do and when to do it. The upshot? Warfighters have to develop their own “inner squad leader.”

“My squad leader talks to me all the time,” he admitted. “I’m gonna do some stupid shit. BAM! Squad leader talks to me: ‘Don’t do that.’ Every one of us needs to build that squad leader [into your brain] who tells you what to do. You’re not doing your PT? Squad leader ought to have a knee up your ass pretty quick!” As you can imagine, Cutler’s presentation was peppered by frequent, self-deprecating laughter.

However, the humorous tone quickly turned somber when he invited Annette, a Gold Star mother, to join him at the front of the room. Cutler shared Annette’s story with the audience, recounting how her son had tragically ended his own life after transitioning out of the military. He then asked everyone to come forward, circle around, and lay hands on Annette while he led the group in the Spartan Pledge.

“I authored it,” he said later about the pledge, “but it doesn’t belong to me. It’s important to me that your readers know [the Spartan Pledge] is hallowed ground. There’s a fiefdom everywhere in our community these days, so I don’t want to attach my personality to this thing. To be clear, I legally own it, but that’s just to make sure no one pulls any bullshit.”

The Spartan Pledge has been featured on a NASCAR vehicle, inked on the bodies of warfighters, and incorporated into special ceremonies across the country. In the final minutes of Cutler’s 2017 Spartan Pledge video, he said that people frequently ask what he plans to do with it next.

“I’m just the author,” he said, laughing. “I’m not doing anything with the Spartan Pledge because it belongs to the community. The question is: What are you going to do with it?”

Tim Cooper is a contributing writer for Coffee or Die and has been a freelance writer for more than 20 years. He is also a certified firearms instructor and soon-to-be-famous recording artist with Fat Chance Records. When Tim is not traveling the world on assignment, which is actually more often than not, you will probably find him at a nearby shooting range or sitting behind a drum kit, staring at his bandmates in bewilderment.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.