Why Special Forces ‘Green Light’ Teams Carried Backpack Nukes in the Cold War

Army Special Forces soldiers and combat engineers or “Green Light” teams carried Special Atomic Demolition Munitions on their backs in secret during the Cold War. Composite by Coffee or Die Magazine.

Each nuke fit in a backpack, and the mission was one-way.

For much of the Cold War, elite US commandos were ready to attack Soviet targets behind enemy lines with backpack-sized nuclear bombs.

Specially trained volunteers served in clandestine roles for nearly 25 years in the standoff of the United States and its NATO allies versus the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact countries. These demolition specialists — pulled from Army combat engineer units, Army Special Forces Operational Detachment Alpha teams, Navy SEAL teams, and the Marine Corps — formed “Green Light” teams.

In the event of World War III, Green Light teams would provide the US military with a less dire option than large-scale conventional warfare and nuclear Armageddon. The “limited nuclear war” strategy suggested using atomic demolition munitions, or ADMs. The prototype designs aimed to achieve an effect akin to nuclear landscaping — condensed nuclear detonations to collapse mountainsides into impassable ground to obstruct invasion routes of enemy forces. These ADMs were far too large and heavy to be carried by lone operators. But after some fine-tuning, the B-54 Special Atomic Demolition Munition, or SADM, entered the Army’s arsenal by 1964.

When Green Light operator Ken Richter was read in on the project, he didn’t think such a weapon could exist.

“I think that my first reaction was that I didn’t believe it,” Richter said, according to a 2014 Foreign Policy article. “Because everything that I’d seen prior to that, World War II, showed this huge weapon. And we were going to put it on our backs and carry it? I thought they were joking.”

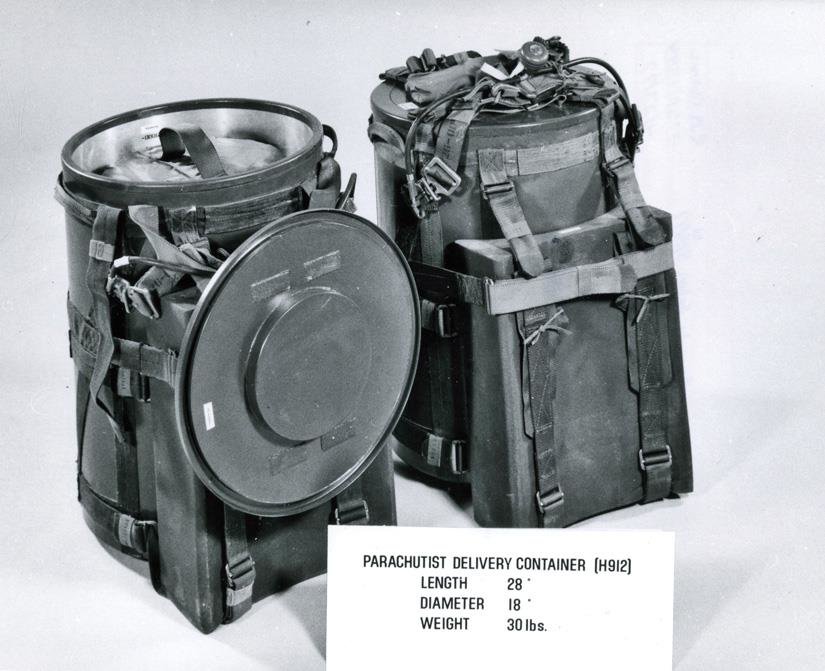

The man-portable tactical nukes were intended for use behind enemy lines, targeting airfields, tank depots, anti-aircraft positions, field command posts, and communications installations, as well as transportation and energy infrastructure. An estimated 300 SADMs were in circulation between 1964 and 1988. The devices were 18 inches tall, weighed roughly 70 pounds, and packed a punch of around 1 kiloton or a little more than 5% of the power of the bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

Green Light teams prepared themselves to deploy the devices in any environment imaginable. In Stanley Kubrik’s satirical 1964 film Dr. Strangelove, actor Slim Pickens’ Maj. “King” Kong straddles a nuclear bomb dropped from a B-52 and rides it toward the ground to his death; the men in Project Green Light would likely face a similar outcome.

Louis Frank Napoli Jr., an enlisted soldier who volunteered for the Green Light assignment, likened the one-way-mission operators to “kamikaze pilots without the airplanes.”

Another former commando told Knight-Ridder Newspapers, “They practiced delivering it by land, sea and air; by static line, free fall, HALO (high-altitude, low-opening parachute) jump and submarine; by car, truck, train, and just plain hiking it in.”

Army Special Forces teams even attempted mobility maneuvers with the SADM in the Bavarian Alps. The snowy environment could make transport difficult. “It skied down the mountain; you did not,” Bill Flavin, who commanded a Special Forces SADM team, told Foreign Policy. “If it shifted just a little bit, that was it. You were out of control on the slopes with that thing.”

Training was done in pairs, but an actual deployment would have called for six-man teams: a commander with the code to arm the nuke, one to carry the device, and four in support. An encrypted code would be delivered over comms. “It would come encoded, and then it would be decoded by two people,” Flavin told Coffee or Die Magazine. “And then it would be compared to the other code. And if all of this matched, then you would arm the device.”

“Believe it or not, for safety and security reasons, it was operated without remote detonation,” nuclear warfare expert William Arkin told Knight-Ridder in 1994. “Somebody actually had to push the button.”

Frank Antenori, an Arizona state legislator and former Green Light member who was awarded the Bronze Star for valor in Afghanistan, understood the assignment intimately. “We’re outside the vaporization range,” he said, “but well within the ‘I will feel the wonderful warm wind that will blow by when it goes off in a second’ range.”

In 1984, after Arkin and his colleagues revealed a description of the SADM from military documents and manuals for the Natural Resources Defense Council, a public outcry commenced. Politicians in Congress were outraged, and the media were equally appalled. The weapons were recalled to the United States, and as the Cold War waned, the SADMs were retired.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2022 print edition of Coffee or Die Magazine as “Nuke-in-a-Bag.”

Read Next: Detachment A: How Special Forces Soldiers Operated Undercover in the Cold War

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.