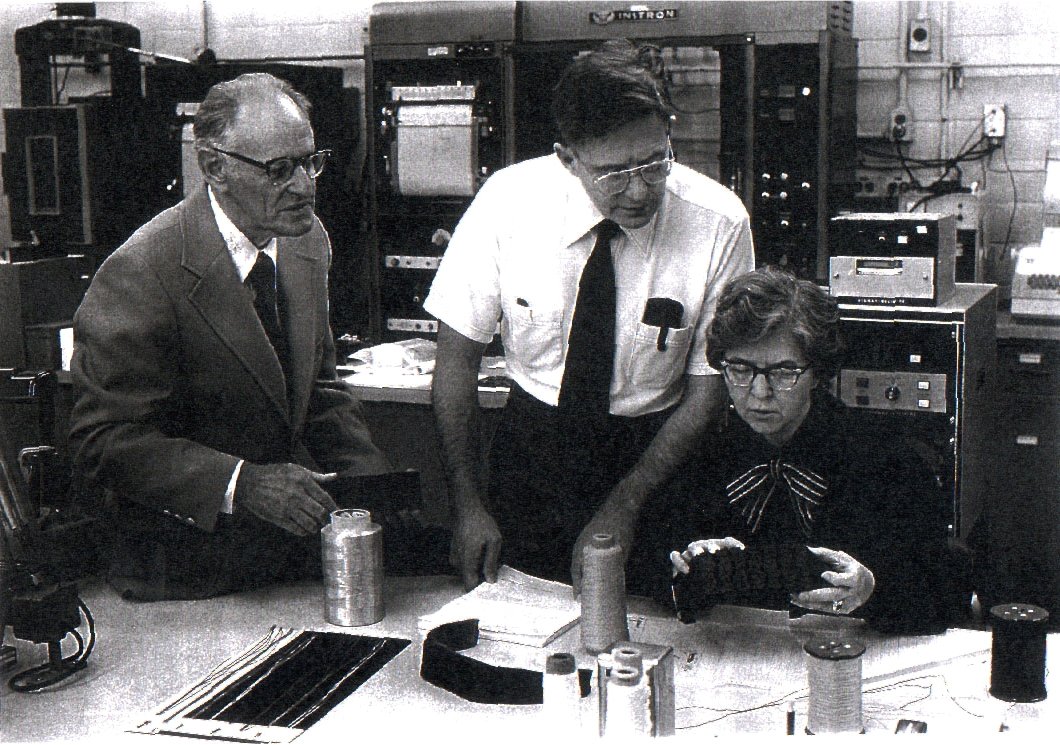

Stephanie Kwolek, who invented the technology behind lifesaving Kevlar. Photo courtesy of DuPont.

On the morning of Dec. 21, 2012, Pennsylvania State Trooper Timothy Strohmeyer was pursuing a man who had just murdered three people. With Strohmeyer and other police closing in, Jeffrey Lee Michael rammed his Ford F-250 truck into another trooper’s patrol vehicle head on, pinning the officer inside. Michael emerged from his truck with a gun, headed toward the trapped officer. To save his fellow officer, Strohmeyer rammed his police car into the back of Michael’s truck. The desperate Michael spun around and dumped a magazine of rounds into Strohmeyer’s windshield. One of the bullets hit Strohmeyer in the wrist and ricocheted to his chest. But rather than kill him, the bullet was stopped by the Kevlar bulletproof vest he was wearing.

“I believe he had intentions of shooting or killing every single person that he came in contact with,” Strohmeyer told the Kevlar Survivors’ Club in 2014. “He killed three people prior to contacting me, and he definitely tried to kill me.”

Strohmeyer is one of more than 3,100 police officers who have escaped death or serious injury because of Kevlar body armor, according to a registry kept by the Kevlar Survivors’ Club, a project of the International Association of Chiefs of Police and supported by Kevlar maker DuPont.

All, whether they are aware or not, owe a deep debt to groundbreaking chemist Stephanie Kwolek.

Kwolek’s parents, immigrants from Poland, taught their daughter a passion that eventually led to her work on the lifesaving fabric.

Her father died when she was 10, but in the years they had together, he was an enthusiastic naturalist and instilled in Kwolek a curiosity about nature and science. The two roamed the woods together looking for animals, wild plants, leaves, and snakes, and Kwolek kept a scrapbook of all her discoveries.

Kwolek’s mother worked as a seamstress and taught her the details of making clothes and working with fabric.

“I used [my mother’s] sewing machine when she wasn’t around,” Kwolek told the Science History Institute in 2007, adding her first clothes were for paper dolls before she upgraded to outfits she could wear made out of fabric. “It was fun and it was creative and it gave me a great deal of satisfaction.”

Kwolek studied chemistry at the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University). It was a time when many women who held doctorates in science lasted only a couple of years as researchers before quitting to raise families or for jobs in education. When she joined DuPont, she worked for 15 years without a promotion.

“I was stubborn,” she said. “I decided I was going to stick it out and see what happened.”

DuPont was one of a handful of chemical companies remaking every area of daily life in the years after World War II, as the use of synthetic materials and plastics began to replace heavier materials in manufactured goods. DuPont created nylon, the first synthetic fiber. When Kwolek arrived in 1946, she joined a team of experienced scientists at DuPont’s Pioneering Research Laboratory.

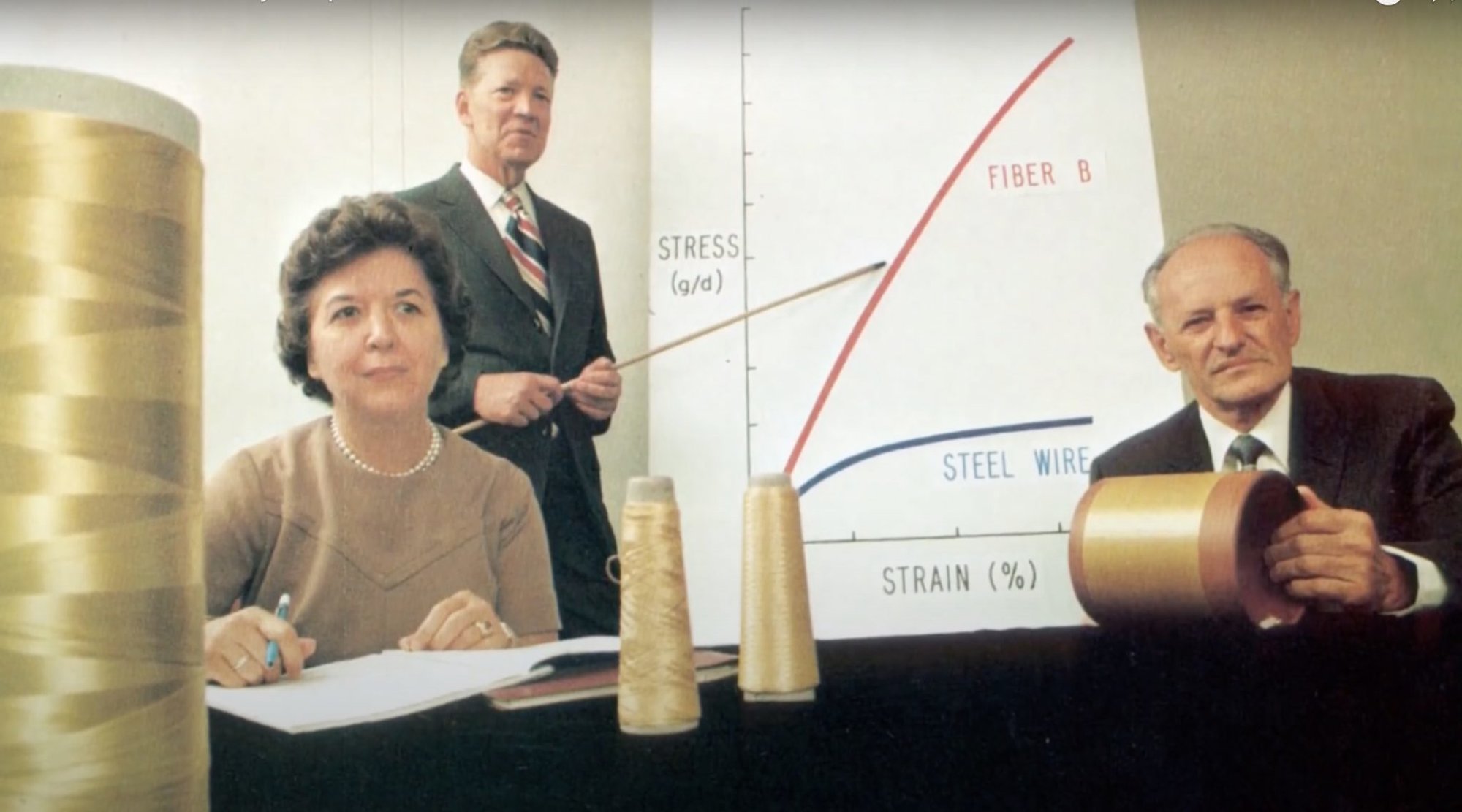

In 1964, there were discussions about a gasoline shortage, and DuPont challenged its researchers to develop a synthetic fiber that could replace steel wire in tires. Kwolek’s experiments in transforming a polymer solution from a liquid into a fiber required spinning the chemicals, not unlike how a tuft of cotton candy is formed. Typically, liquids in her groupings were thick and clear and looked like corn syrup, but one solution came out thin, watery, and milky. The liquid was so different that the operator of the machine used to spin the fibers refused to use it, out of fear it would break the equipment.

Nevertheless, Kwolek insisted, and when it was spun into a fabric, test results were beyond what any at DuPont had ever seen before. The fiber was five times stronger than steel. “It wasn’t exactly a ‘eureka moment,’” she told USA Today in 2007, adding she didn’t want to tell management at first because she was afraid the tests were wrong. “I didn’t want to be embarrassed. When I did tell management, they didn’t fool around. They immediately assigned a whole group to work on different aspects [of the material].”

Kwolek’s fiber became the basis of Kevlar, which is used in more than 200 applications today. This long list includes cut-resistant gloves for chefs, armored vehicles, helicopter rotor blades, the landing cushions on Mars rovers, and everyday objects like athletic shoes, hockey sticks, and frying pans. Kevlar also provides material support in the aerospace, marine vessel, and rail industries.

Beyond Kevlar, Kwolek consulted on Nomex, the flame-resistant nylonlike material firefighters use in their bunker gear, and Lycra spandex, a springy material that makes clothes stretchy. Kwolek was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 1995, the fourth woman of 113 inductees at the time. A year later she accepted the National Medal of Technology and Innovation, and in 1997 she received the Perkin Medal, which is considered one of the highest honors in the chemistry field. She was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 2003 and died in 2014 at age 90.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.