Stephen Crane Conveyed War’s Horror, Existential Angst Like No Other

“I heard somebody dying near me. He was dying hard. Hard. It took him a long time to die … The darkness was impenetrable. The man was lying in some depression within seven feet of me. Every wave, vibration, of his anguish beat upon my senses.” — Stephen Crane in War Memories

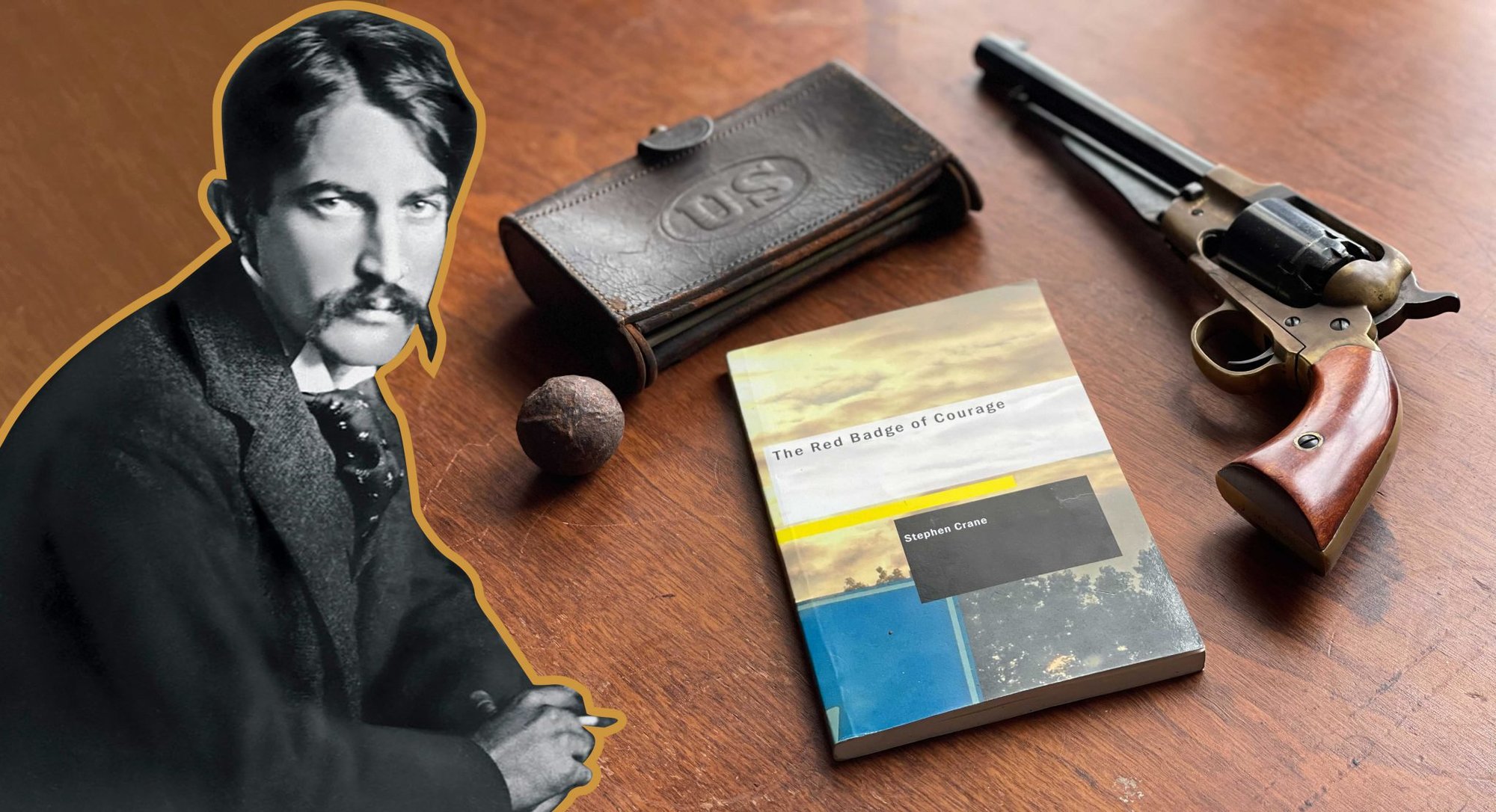

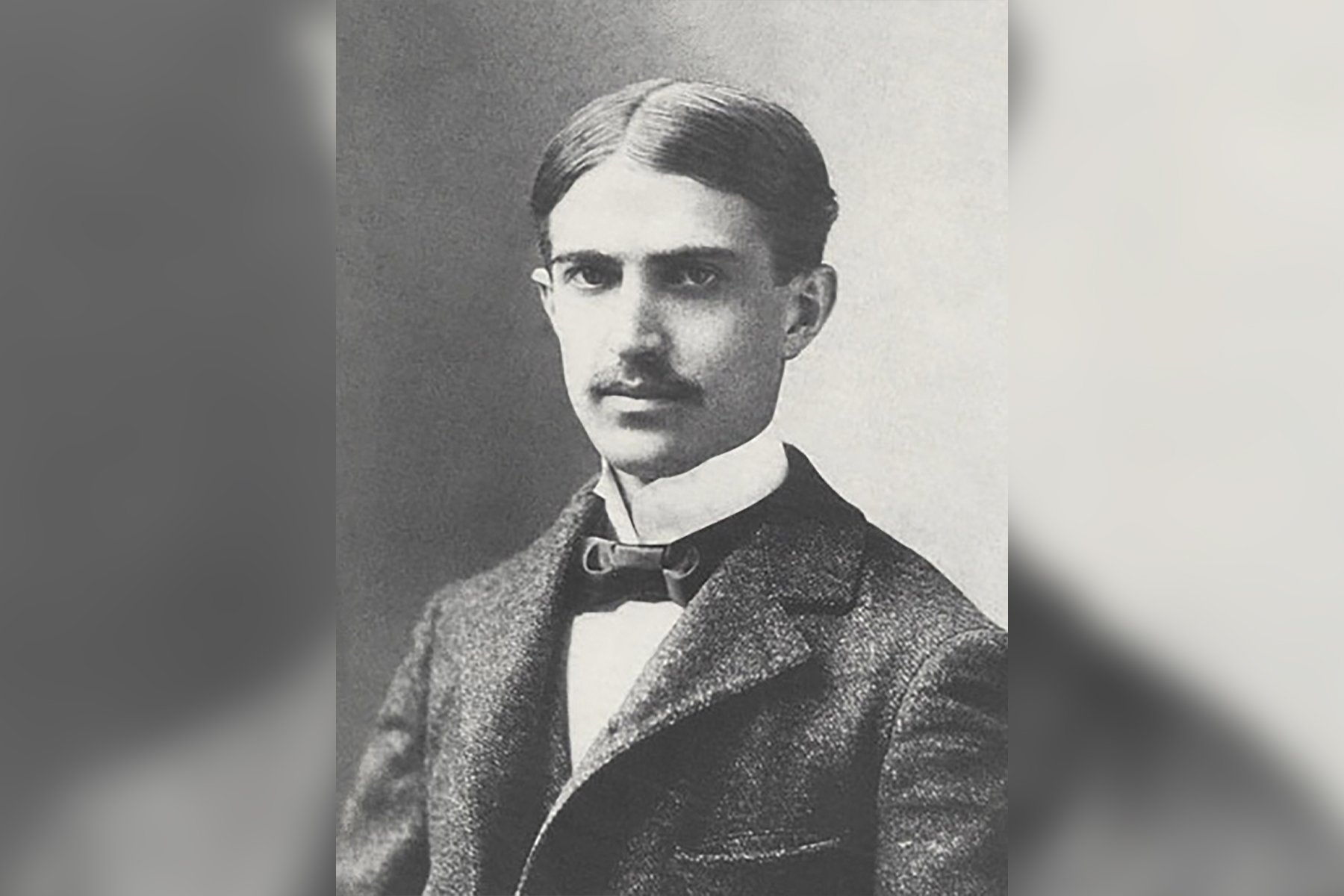

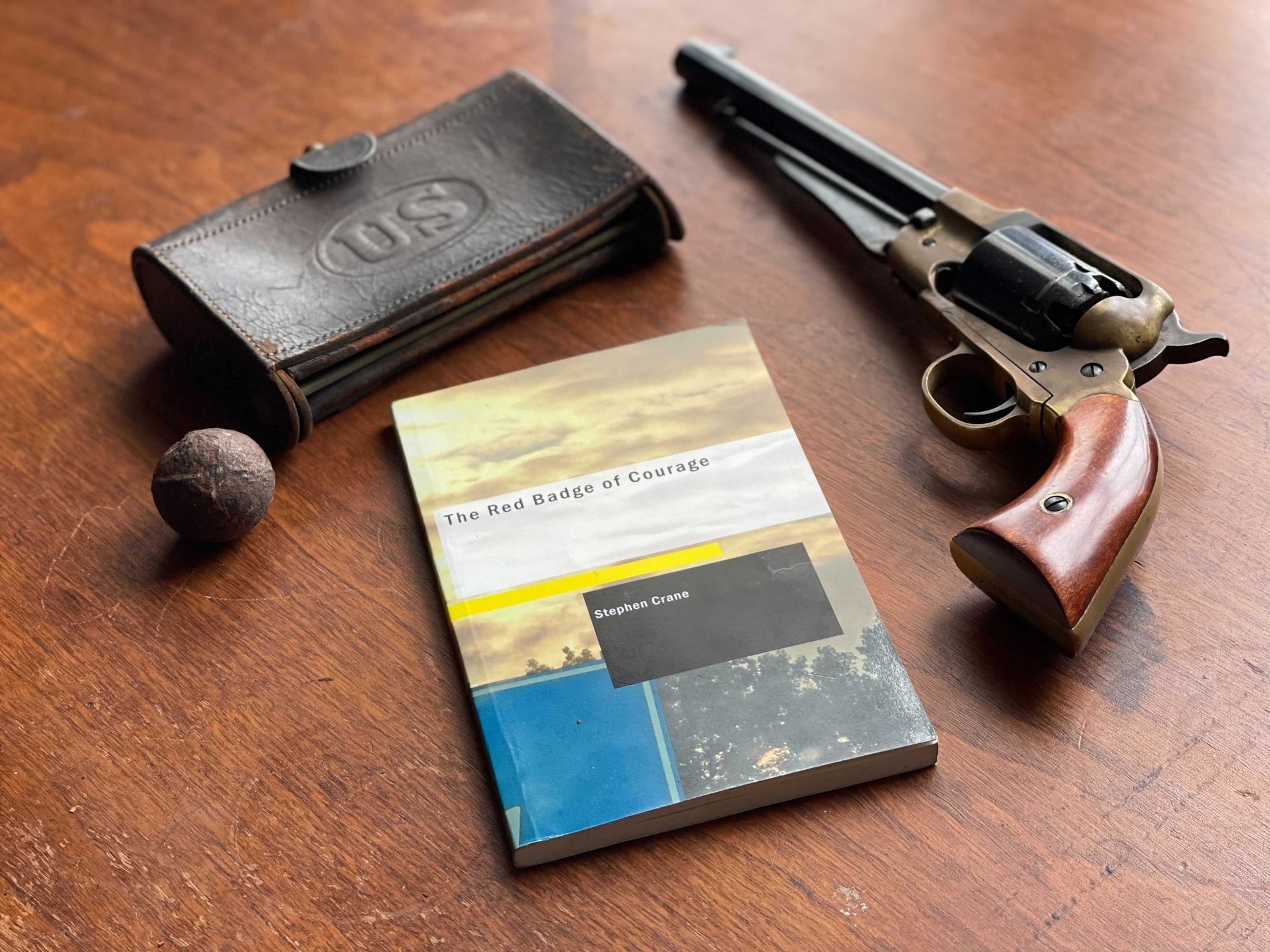

Stephen Crane wrote about war long before he ever saw combat as a journalist. Crane was born after the Civil War, and despite never having pulled a trigger in that conflict, he wrote vivid prose in The Red Badge of Courage about combat he hadn’t seen. The novella was a plotless narrative of a single soldier’s humiliating cowardice and eventual redemption in the Civil War. It made Crane internationally famous in 1895 because he wrote so viscerally readers thought he must be a combat veteran.

“Crane utilized his keen observations, as well as personal experiences, to achieve a narrative vividness and sense of immediacy matched by few American writers before him,” his Poetry Foundation page reads.

Crane’s writing career only lasted about seven years, but in that time, he earned his place as “one of America’s foremost realistic writers.”

In War Memories, Crane wrote, “An expression of life can always evade us, we can never tell life, one to another, although sometimes we think we can.”

In modern writing by veterans about war, it sometimes feels like the combat-veteran community denigrates the works or perspective of those who never faced the enemy in combat. It’s a dick-measuring tradition as old as warfare. Battle-hardened Roman legionnaires probably looked at the noobs and said, “What, you haven’t fought the Gauls yet? Get the fuck outta here.” In the Marines, the joke after coming home with a Combat Action Ribbon was “If you don’t have a CAR, how you gonna get to the party?

Crane never wrote a full novel. His poems rarely had titles. His writing sometimes seems like hastily dashed thoughts you’d jot down on your phone at a bar — if those thoughts captured something like universal truths about the beauty in darkness and the endless contradictions in the human experience. You could say Crane was dabbling in postmodern irony long before it was cool.

In the desert

I saw a creature, naked, bestial,

Who, squatting upon the ground,

Held his heart in his hands,

And ate of it.

I said, “Is it good, friend?”

“It is bitter—bitter,” he answered;

“But I like it

“Because it is bitter,

“And because it is my heart.”

Crane would lay open his own contradictions and allow the reader to reflect on the conflicts and hypocrisy inside themselves. It can be a dangerous and exhilarating thing for a writer to make people confront their biases and challenge the way they look at the world. And in that sense, Crane was a dangerously exhilarating writer.

Combat veterans often have an ivory tower complex. When/where/how you served matters. The wars have given us a class structure: Did you deploy? If you deployed, did you leave the wire? If you left the wire, did you engage the enemy? If you fought, were you wounded? If you got a Purple Heart, how bad was it? Or, to quote Ken Jeong in The Hangover Part II, “But did you die?”

It’s a trap.

“If you didn’t experience what I went through, you can’t comment on it” is a fallacy. Just ask retired Marine Gen. and former Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis.

Sometimes the person with the best perspective is the artist and observer, not the participant. Sebastian Junger was a lifetime war correspondent. He never fired a weapon, but he’s seen battlefields across the globe and has a unique perspective on veterans and warfare. British author Rudyard Kipling wrote raw, authentic war poetry and stories from India that endure to this day, but he was never a soldier. Ernest Hemingway, who was inspired by Stephen Crane, was a war correspondent but never a military veteran.

Crane was full of contradictions. A Methodist preacher’s son from a devoutly faithful family, Crane once defended a prostitute in court in New York, and his first novella, Maggie: A Girl of the Streets, was about a hooker. Despite his religious upbringing (and perhaps because of it), Crane doubted God’s existence. He wanted to live the bohemian lifestyle and loved spending money on parties. He never married but had a common-law wife.

In a simple, five-line poem, Crane asks us to contend with the notion that humanity is simply debris pushed inexorably down a channel by a roiling rush of water.

A man said to the universe:

“Sir, I exist!”

“However,” replied the universe,

“The fact has not created in me

A sense of obligation.”

In Crane’s verse, no one has control over his own fate, and the universe (see: God) hasn’t the time or inclination to give a single fuck. Crane reframes our search for answers and notions of cosmic significance as narcissism. If there is a God, we are about as important to him as ants on a stick he callously tosses into a campfire.

For we few, we happy few, we band of brothers, this notion is best illustrated by the bullets, the mortars, the shrapnel that have come for us and our friends with varying degrees of success. These instruments of death don’t care who you are.

Crane died in 1900 at the age of 28, just missing the Dead-at-Twenty-Seven Club with Morrison, Hendrix, Joplin, Cobain, and Winehouse. Between the intimacy of his writing and his self-destructive partying, Crane belongs in that class of artistic geniuses.

When he knew he had tuberculosis, he acted like he didn’t care. Just before his death, he had his girlfriend and another woman tie him up so he could write about the experience in his short story Manacled.

He describes his concept of self-destruction in The Open Boat, regarded by some as one of the greatest American short stories:

“He at first wishes to throw bricks at the temple, and he hates deeply the fact that there are no bricks and no temples.”

In the last four years of his life, Crane finally saw combat as a war correspondent during the Greco-Turkish War and Spanish-American War, but he never fired a shot himself. Despite having successfully written so much about war and death, he was unsure of himself and his work until he witnessed combat. In 1897, he told Joseph Conrad (the author of Heart of Darkness, the book that inspired Apocalypse Now), he “now knew that the battle scenes in The Red Badge of Courage were ‘all right.’”

A lot of veterans struggle with the feeling that their service wasn’t sufficient. Some feel guilty for having only served in peacetime, or for not deploying, or for not deploying enough. Maybe I didn’t contribute enough. Maybe I didn’t suffer enough. That feeling is a form of survivor’s guilt.

Stephen Crane may not have been a military veteran, but his work is proof that combat isn’t the be-all and end-all. You don’t have to put a bullet in another man’s head to understand the contradictions in war, to suffer, to be fully human in your need to cry out, “Sir, I exist!”

Read Next:

J.E. McCollough served nine years in the Marine Corps. He fought in Iraq in 2003 and 2004 and is the recipient of a Purple Heart.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.